After 30 hours of hearings, Barrett remains a blank slate

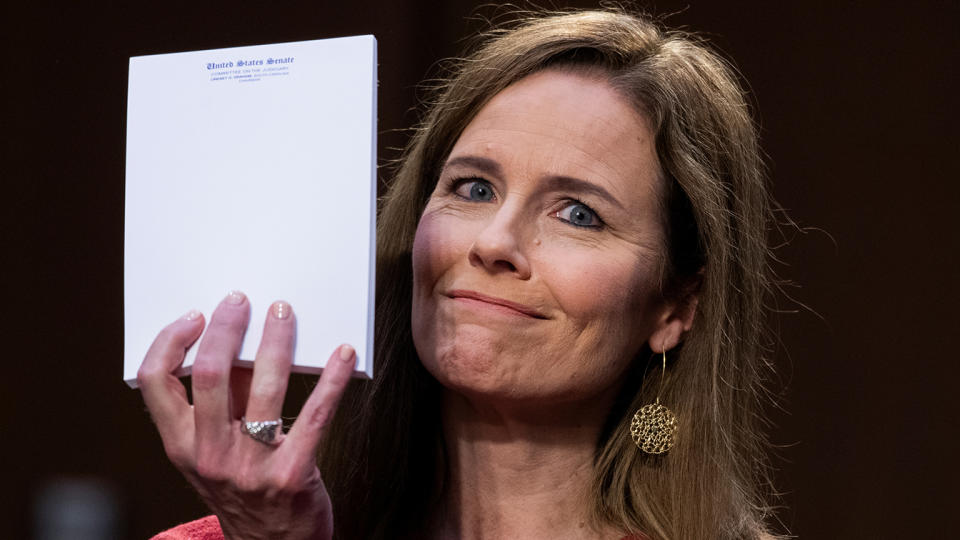

WASHINGTON — Perhaps the most symbolic and telling moment of the Senate hearings on the nomination of Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court came on Tuesday, when Sen. John Cornyn, a Republican from Texas asked about the notepad on the desk before Barrett. “Is there anything on it?” Cornyn asked.

In response, the 48-year-old smiled and held up the pad for the committee members to see. Other than the letterhead of the U.S. Senate, it was completely blank.

Cornyn found the lack of notes “impressive,” and the right seized on the notepad as a symbol of an eminently prepared nominee, a federal judge and former Notre Dame scholar who knows the law so well that notes were unnecessary. Her memory must have been pretty good too.

Her progressive critics, however, who are legion, saw something else.

For some, her refusal to take notes was disrespectful of the process, a sign that Republicans had known the fix was in from the start and were going through the motions of what Sen. Amy Klobuchar, D-Minn., called “a sham” of a hearing.

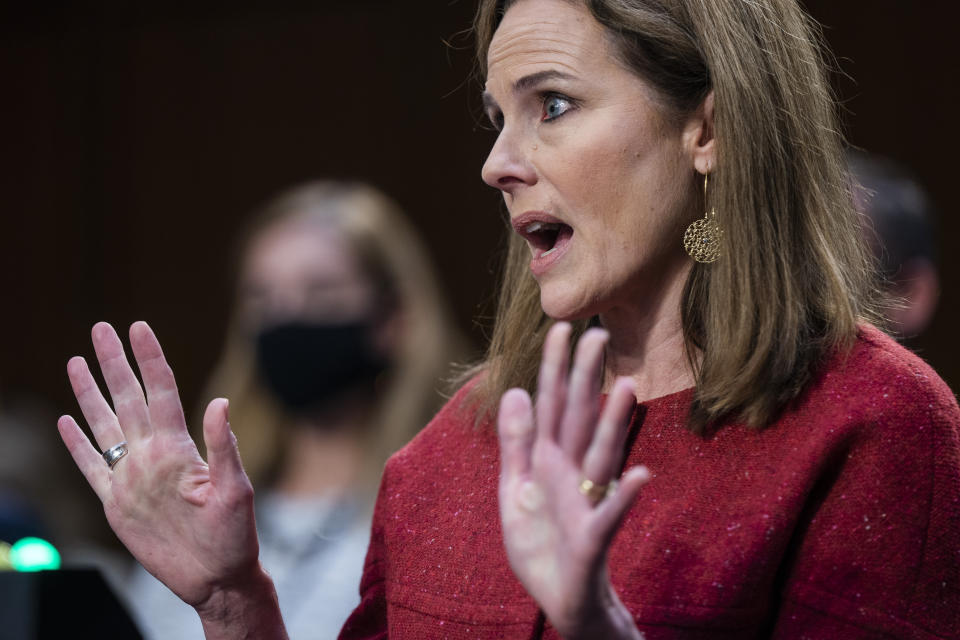

Others saw the blank sheet as symbolic of Barrett’s inscrutability, her stubborn refusal to be drawn into a discussion of her beliefs. Republicans have argued that something they call the Ginsburg Rule — in reality, little more than an excuse — allows her to avoid answering questions about cases that might come before the court. And since the Supreme Court might rule on any number of issues, from the commerce clause to same-sex marriage, she could keep her bat safely on her shoulder as Democrats threw hard pitches her way.

The refusal to explain her convictions left an opening for critics to define Barrett, based on her copious record of writings as a law professor, as well as her frequently provocative opinions and rulings during her three years on the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals. Twitter users quickly used Photoshop to “fill” the notepad for the nominee. “Chopping Block,” read one faux agenda, listing what Democrats feared was under threat in a Supreme Court with a clear conservative majority: the Affordable Care Act, abortion rights, marriage equality and the Establishment Clause.

From the time Senate Judiciary Committee members gave their opening remarks to Thursday’s testimony from witnesses for and against the nominee, Barrett received more than 30 hours of consideration and scrutiny. The Senate can also refer to her 69-page response to a questionnaire all judicial nominees are required to answer. But the woman Republicans say is supremely qualified to sit on the court and Democrats warn will usher in a new era of far-right jurisprudence remains an enigma.

Democrats were increasingly frustrated by their inability to coax or persuade Barrett into disclosing anything about what she believed. At one point, Sen. Kamala Harris, D-Calif., asked Barrett if the coronavirus was infectious and cigarettes carcinogenic. A puzzled Barrett said yes to both.

Harris quickly followed up with another question whose answer is equally a matter of established science: “Do you believe that climate change is happening?”

Here, there would be no satisfaction. Barrett retreated to the stance she had taken from the start: She could not offer her opinion on a “matter of public policy,” especially one that was “politically controversial” and that the Supreme Court might have to address.

So it went when Sen. Klobuchar asked about voter intimidation, which is illegal by what the legal profession calls the “black letter” of federal statute law, and when Sen. Richard Durbin, D-Ill., asked about the Voting Rights Act. Sen. Dianne Feinstein encountered the same reluctance after asking Barrett if she thought, like some constitutional originalists, that federal programs including Medicare and Social Security were unconstitutional.

Barrrett said she could not “answer that question in the abstract.” Nor could she answer questions about a hypothetical case involving Medicare that came before her because, as the elusive nominee put it, “I also don’t know what the arguments would be.”

Deftly and consistently, Barrett closed off every line of inquiry from Democrats. Her past writings, including a 2017 article critical of the Affordable Care Act, were the work of a law professor, not a judge, and thus had no relevance in the hearing, she maintained. Same went for most questions on gun rights, abortion and health care.

“I’m not going to answer hypotheticals," she said. “I can’t apply the law to a hypothetical set of facts.”

One of their Republican colleagues, the perennially irascible Sen. John Kennedy, asked Barrett, “Do you hate little warm puppies?"

Here, her answer was unambiguous, for once: "I do not hate little warm puppies." Though there were no puppies in the Barrett household, she volunteered that there was a chinchilla. The chinchilla is reportedly “very fluffy.”

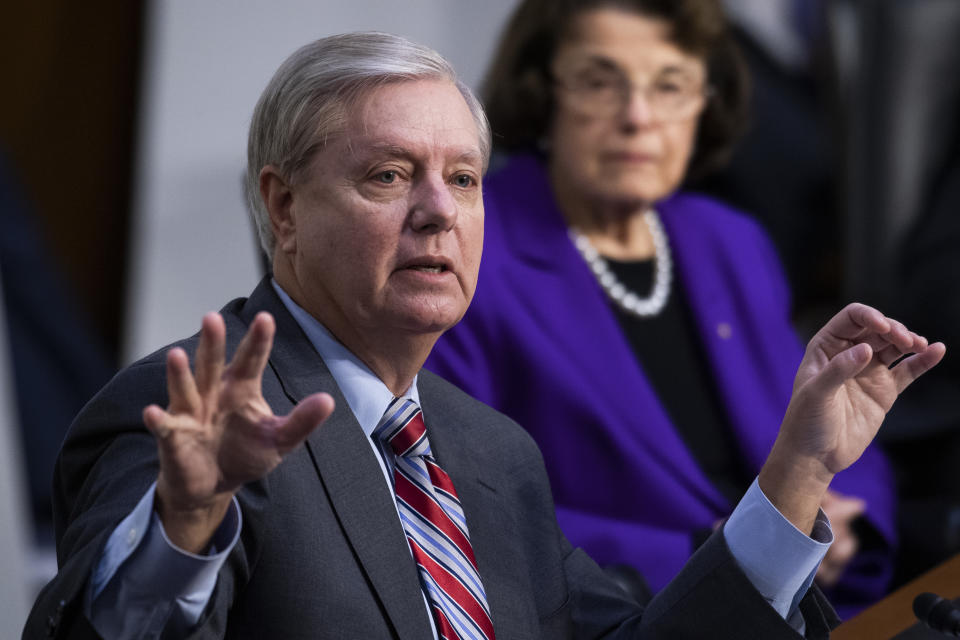

By the end, Democrats were bitter over what they saw as a rushed and unsatisfactory process, although the histrionics from both sides that characterized the confirmation hearings for Justice Brett Kavanaugh were mostly absent. Sen. Lindsey Graham, the committee chairman, earned thanks from the ranking Democrat, Sen. Dianne Feinstein, for the way he conducted the hearing — “This has been one of the best set of hearings that I’ve participated in,” she said, to the fury of progressives — but cordiality has never changed the outcome of a Senate vote.

“Now, the game has been since she’s been nominated to get back at Trump and I understand — it’s probably what I would do if I were y’all,” Graham said, in what these days counts as an olive branch on Capitol Hill.

Democrats depicted her as a tool of Trump, one who — for all her obvious learning and sophistication — would ultimately execute his promises and, perhaps, they warned, help him improperly secure a victory in next month’s presidential election.

In what amounted to a law school seminar, Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, D-R.I., used his questioning time to tease out connections between Trump-nominated judges and “dark money” corporate interests that fund conservative judicial groups like the Judicial Crisis Network and the Susan B. Anthony List. It is those groups, Sen. Whitehouse argued, that have foisted Barrett on Trump, and on the nation. He denounced “forces outside of this room who are pulling strings and pushing sticks and causing the puppet theater to react.”

None of this fazed Republicans, which reinforced the appearance that Barrett’s confirmation was a foregone conclusion. “If anybody in America is ready to go to the Supreme Court, it’s Amy Barrett,” said Graham. He will hold a committee vote on her nomination on Oct. 22. The full Senate will vote on her nomination thereafter. She is expected to pass, but only narrowly. Graham’s invocations of the long-ago days when 96 members of the Senate voted to confirm Ruth Bader Ginsburg — whose death last month opened up the seat Barrett was nominated to fill — are unlikely to lead to a bipartisan renaissance.

Graham was not the only senator to talk about history. It fell to Senator Durbin to point out that the Barrett hearing had become a battlefield on which both sides aired grievances dating back decades.”Some of us have Robert Bork stuck in our craw,” he said. “Others have Merrick Garland stuck in their craw.”

Bork was nominated to the Supreme Court in 1987. Expecting an “intellectual feast” on the high court, he found his nomination scuttled by Democrats who picked apart his arch-conservative views. Since then, nominees have been much more cautious about revealing what they believe, lest they too fall victim to a “Borking.”

If the Republicans cannot forgive what happened to Bork, then Democrats are certainly unwilling to forgive what happened to Garland. Nominated to the Supreme Court in early 2016 by President Obama to fill the seat of the late Justice Antonin Scalia, he was refused even a cursory hearing by Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell.

Nor, for that matter, did Barrett’s own reassurance of judicial independence do much to, well, reassure. That may be because her steadfast refusal to say what she believed led to speculation that, whether fairly or not, she would serve the very forces that installed her.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: