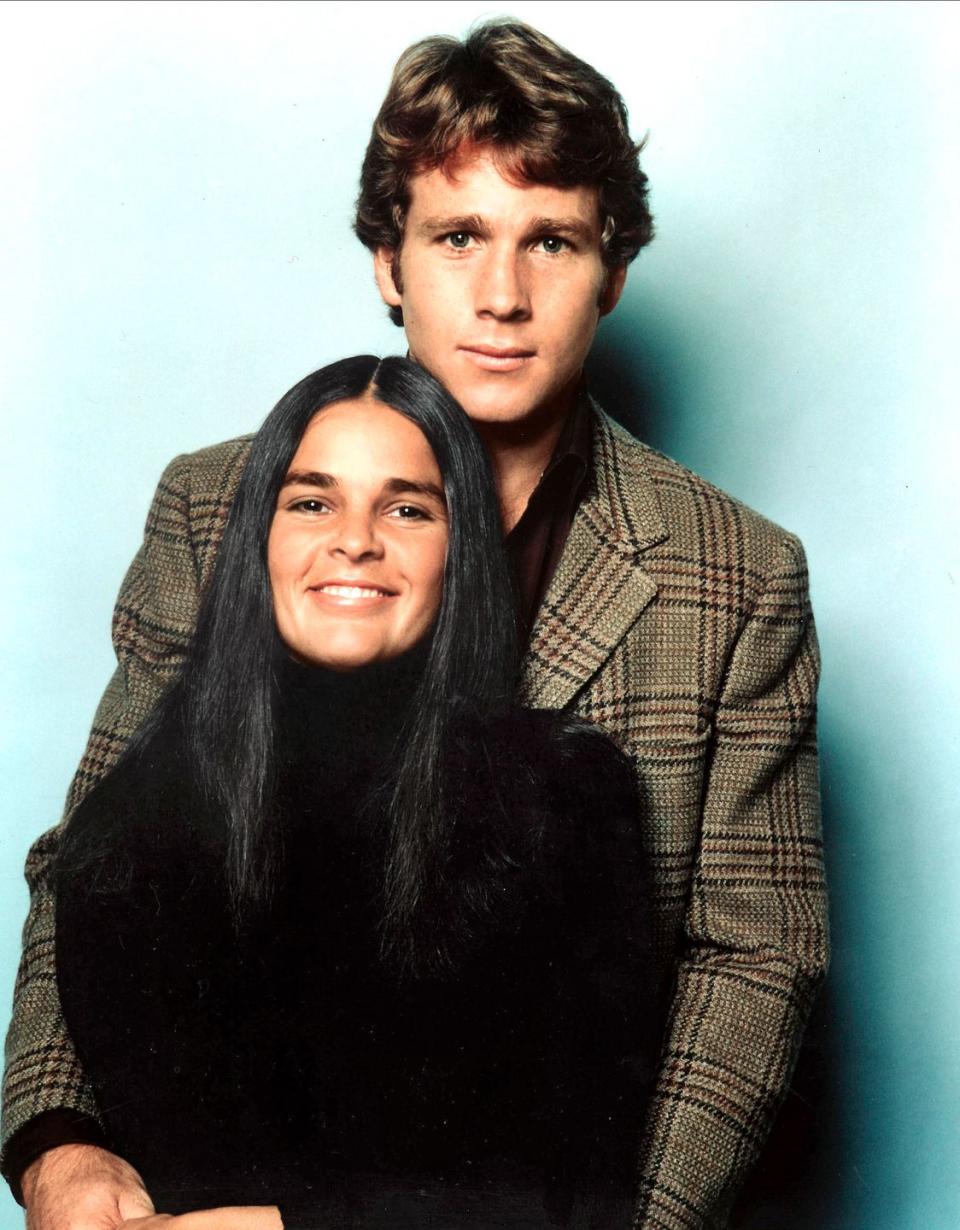

Ali MacGraw and Ryan O'Neal Talk Love Story at 50

What can you say about a film that refuses to die?

When Love Story, the tale of a doomed romance between Ivy League students Oliver, a rich preppy, and Jenny, a spirited social zero, went from a slender paperback to an unexpected box-office smash despite a downbeat ending where Jenny dies of, well, something. In 1970, it was received with sniffles, snickers, and seven Oscar nominations. A cathartic respite for a country in chaos, the little-tear-jerker-that-could took in more than $130 million worldwide, rescuing Paramount Pictures from financial disaster. Sure, critics poked fun at its naivete, but even Kurt Vonnegut once admitted to Harvard’s Signet Society that criticizing Love Story was like “criticizing a chocolate eclair.”

Five decades later, the film has proven more durable than its own fictional marriage, and leads Ryan O’Neal and Ali MacGraw are now celebrating the golden anniversary of the movie that made them overnight stars and forever linked them in the public eye. “It’s been a fast 50,” says O’Neal. “I don’t have those relationships with my wives!”

Both actors were Hollywood novices when Love Storycame around. MacGraw was hunting for the perfect follow up to Goodbye, Columbus, a bittersweet romantic drama that had won her a Golden Globe for New Star of the Year, and after rejecting several roles, she finally read the script for Love Story.

Like Jenny, MacGraw was a sharp-tongued smarty pants who’d attended Wellesleyon a scholarship. “We share the same energy,” she says. Back in college, MacGraw had even known author Erich Segal when they appeared together in a college production of All’s Well That Ends Well. Despite this familiarity, Love Story caught her off-guard. “I cried, and I thought I was crazy,” says MacGraw, then she immediately read it again, elbowed her husband-to-be, Paramount producer Robert Evans, and convinced him she’d found her next part.

Evans thought Love Story was cloying, but he greenlit a casting search of 1,000 contenders to find MacGraw a co-star. Meanwhile, after five seasons on the nighttime soap opera Peyton Place, O’Neal was lusting to make the transition to film. At O’Neal’s first screen test with MacGraw, the two kissed so hard that the actor, hoping to make the leap from TV to film, was sure he had landed the job. Then a friend with the inside scoop told him MacGraw had kissed everybody like that. Nevertheless, O’Neal says, “the chemistry has managed to sustain itself for 50 years.”

Onscreen, MacGraw and O’Neal made an independent, combative couple, and Jenny and Oliver are united in their stubbornness. Their marriage is founded on defiance: She’s a working class kid who shuns pitying stereotypes; he’s a child of privilege who can’t accept condescension from his father, who hopes to install a pliable son on the Supreme Court—or from his hard-headed girlfriend. To keep her from moving to France, Oliver impulsively proposes. “Why?!” Jenny blurts. “Because,” he shrugs. She can’t argue with that, so she agrees.

With maturity, it’s clear that the turbulent pair are not a healthy romantic ideal. And yet, as cynicism cast shadows over the Summer of Love, and Hollywood studio system that created Casablanca gave way to a new generation of rebels, audiences adored a climax where the heroine’s final words include, “Screw Paris.”

Critics, however, were polarized. Even Love Story defender Roger Ebert quipped that Jenny was stricken with what he called Ali MacGraw Syndrome: “the medical condition in which you grow more and more beautiful until you die.” Which is a compliment to MacGraw. She’d shown up on set expecting to be painted a sickly blue. The make-up team looked at her bare face and waved her onward. “Which was like saying, ‘You look like death,’” she laughs.

Yet, as the pair filmed Jenny’s death, O’Neal was overwhelmed by the power of MacGraw’s performance. “It all caught fire for me there,” he says. The crew misted over, and so did he. “She put her arm around my head, my hair. I just couldn’t stop crying. I loved her. I knew this would soon be over.”

Well, yes and no. The night of the premiere, the crowd also sobbed through a forest’s worth of tissues and the then newly built Gulf and Western building lit up its windows to beam “LOVE STORY” over Manhattan. “By the next day, there were lines around the block all over the country, and then the world,” says MacGraw. “It was just stupefying. Totally insane.”

From then on, MacGraw and O’Neal’s bond would never be over, both in the imaginations of fans and in the shared surreality of sudden fame. Of strangers needing to tell them their love stories: their first dates, their engagements, their struggles. Of popping up in political headlines as presidential candidate Al Gore’s opponents accused him of claiming that he and wife Tipper had inspired the novel. Of the inescapability of “Theme From ‘Love Story,’” the mournful instrumental that won composer Francis Lai an Oscar. “Every time I went to a restaurant anywhere in the world, the band would start with Love Story,” says O’Neal. “I guess you get used to it after a while. I don’t know if I ever did.” That melody was even played last January at the funeral procession of Iranian major general Qasem Soleimani. (“Oh, stop it!” yelps O’Neal. “His funeral!?”)

To keep Love Story alive, Harvard hosts an annual screening for freshman. “It’s a little bit like Rocky Horror,” says MacGraw, “where they scream, ‘Love means never having to say you're sorry!’ at the screen.”

If she’d had more experience, she would have pushed back on that line. “It doesn’t mean anything!” MacGraw groans. “I’ve learned that we can make terrible mistakes with people we love.” What wisdom would she say today? “Try not to do it again—and try to clean up the hurt,” says MacGraw. “It’s the truth.”

You Might Also Like