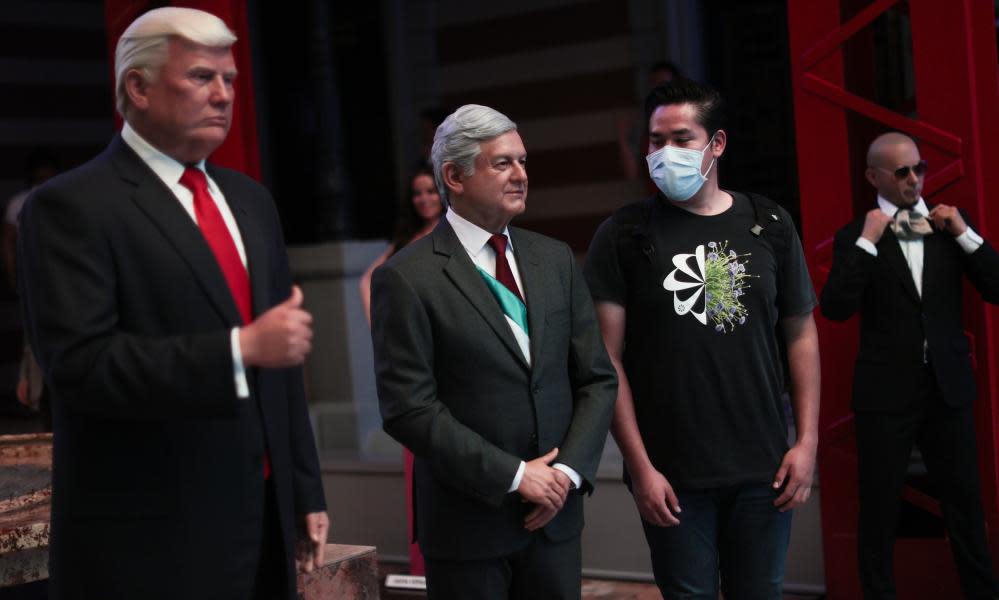

America Through Foreign Eyes review: a Mexican take on the US under Trump

In 1830, Lorenzo de Zavala, the principal author of the 1824 Mexican constitution, found himself in exile. So decided to visit a nation he had long admired.

Related: 'Trump has a different leadership style': David Rubenstein plays it by the book

“There is not a more seductive example for a nation that does not enjoy complete liberty,” he wrote in his 1834 Journey to the United States of North America, “than that of a neighbor where are found in all public acts, in all writings, lessons and practices of an unlimited liberty.”

Zavala – who in 1836 would serve briefly as vice-president of the Republic of Texas – was impressed by the federal system and local democracy. He was also struck by the country’s material prosperity, observing that “one of the principal causes of the stability of the institutions of the United States of North America is the fortunate situation of the great majority of the people”.

Nearly two centuries later, another Mexican politician echoes this sentiment, writing that admirers and detractors alike found in the US “a middle-class society non-existent in their own countries”. Unlike Zavala, however, Jorge Castañeda’s aim is not to write “from a Mexican perspective”, but to speak as “a sympathetic foreign critic”.

While Zavala’s reflections were the product of a whistle-stop tour, Castañeda’s have been forged over a longer period. He was Mexico’s foreign minister from 2000 to 2003, but he received a bachelor’s degree from Princeton and has spent decades living between the two countries. Now teaching at New York University, his motivation is to “examine with fresh eyes” the questions of previous observers, while also sharing “Americans’ affection and concern for the state of their nation”.

Although Castañeda accepts that the US middle class and its prosperity was initially built on the exclusion of non-white people, he argues that today it is both more diverse and at great risk because of rising inequality.

The first part of his book examines this middle-class world, how critics find an unpalatable “sameness” but also the relish with which its middlebrow culture, as exemplified by Hollywood films and McDonald’s, reaches a global audience.

Castañeda also attempts to puncture the myth of American “exceptionalism”, which he labels a “home-baked peculiarity”, and criticises the US public for its “absence of a sense of history”. Yet in the same chapter he also praises that public for its “extraordinary sense of humour”.

Humour bridges this historical gap, he argues, because it “functions frequently as a substitute for the historical self-criticism of other nations”. Where other nations might brood or self-flagellate, the US uses humour as a way to critique its shortcomings. It is not an entirely convincing argument, but it’s difficult to disagree with Castañeda’s conclusion that “America will need its sense of humor more than ever in the coming years”.

It is not a convincing argument, but it’s difficult to disagree with Castañeda’s conclusion that “America will need its sense of humor more than ever in the coming years”.

The latter half of the book turns to more specific policy issues, put in thoughtful pairings. In a chapter on drugs and immigration, Castañeda rightly identifies “pragmatic and hypocritical” attitudes to both. Yet within the same chapter – and this happens across the book – he veers from sections heavy with statistics to paragraphs of unmoored generalisation.

For instance, Castañeda claims “the millions of Latin Americans who have arrived in the United States over the past 40 years … experience an easier insertion in American society than the inhabitants of the Maghreb, sub-Saharan Africa, Turkey or Syria do in Europe.” That ignores the colonial context for Muslim immigration to Europe, for instance Algeria’s connection with France, and also skirts the difficulties people from Latin America continue to face in the US.

The next chapter pairs race and religion, but starts with another troubling claim: that neighbours like Brazil and Cuba “encounter different problems than America: poverty, inequality, violence, and corruption”, and that the US is the only rich country where questions of racism stem from slavery. That simply isn’t the case, as the global embrace of the Black Lives Matter protests shows. In Europe, wealthy former colonizing powers continue to deal with race, while all the nations of the Americas struggle with similar social problems, many born of a common history of colonialism, native land dispossession and African slavery.

Castañeda saves his main frustrations for his penultimate chapter, which examines mass incarceration, the death penalty, guns and intelligent design. To him, these amount to a “breach of contract with liberalism and tolerance” and make the US “an outlier with regard to other rich nations”. These are parts of US culture outsiders struggle to understand, but ones that show no sign of going away. From there, Castañeda concludes with a clear assessment of the challenges ahead: climate change, relations with China and the larger question of where the US sits in the world.

Related: A disputed election, a constitutional crisis, polarisation … welcome to 1876

While America Though Foreign Eyes covers a lot of contemporary issues, it could have benefited from a few more stories of Castañeda’s own experiences. In addition, there are a number of significant errors, including incorrect dates for the abolition of slavery in France (1794, not 1791, never mind that it was reinstated in 1802 then re-abolished in 1848) and Britain (1833, not 1812).

Missteps aside, Castañeda provides a detailed summary of the issues facing a country of which he remains fond, saying Americans deserve “a far more effective, modern, and well-suited political system than the one they are today condemned to suffer”.

That the US would be in such a position might have been unimaginable 190 years ago, when Zavala wrote of an observer casting “a rapid glance over this gigantic nation which was born yesterday and today extends its arms from the Atlantic to the Pacific and the China Sea” and asking “the question: “What will be the final outcome of its greatness and prosperity?”

Carrie Gibson’s latest book is El Norte: The Epic and Forgotten Story of Hispanic America