'I Accidentally Killed My Best Friend's Daughter'—How Two Women Recovered From the Worst Pain Imaginable

"Here I am spinning,” four-year-old Easton Miller crooned along to the country song on the radio in the back of his mom’s Toyota Highlander. Cassie Miller smiled, making the six-mile drive over the rural roads of Tenino, Washington, to pick up her friend’s son, Wyatt, and drop the boys at preschool on her way to work. But as she pulled into Brynn Johnson’s circular driveway and got out, three-year-old Wyatt was throwing a tantrum, screaming, crying, and demanding to not go to school. When his mother went to fetch his car seat, he bolted back into the house.

As Brynn went to round up Wyatt, her 17-month-old, Rowyn, ran out to say hello in her turquoise and white polka-dot jammies. Cassie gave her a squeeze on the chin the way she always did—she adored the exuberant girl with her blond curls. The chaos continued until Wyatt, still in tears, was finally buckled in next to Easton. “We can go now; he’ll be OK once we’re on our way,” Cassie reassured her friend as she climbed back into the Highlander. Brynn stood outside the house in her white bathrobe and waved goodbye.

It was 8:18 A.M. when Cassie put the car in drive, relieved to be getting underway. Then, as she rolled forward, she felt a bump. “We both locked eyes in the rearview mirror,” says Brynn. “Like, what the hell?”

The bump was Rowyn.

Before That Day

The friends, both 34 now, can’t remember when they met. But it was around the time Cassie moved to Tenino 11 years ago, and eventually Brynn became a fixture in her kitchen doing her hair—“different cuts, different styles, blond, dark purple, and just about every other color under the sun,” she says—as they talked away the hours. Brynn was so outgoing she was an easy friend for someone new in town. For her part, Brynn loved the way Cassie cracked her up, how she also seemed to walk through life with steel-toed goodness. Over the years their conversations moved to the SandStone Salon & Spa, where Brynn took a job, and shifted from romance and karaoke to husbands and diapers. Their boys were born nine months apart, and they were both pregnant again on their thirtieth birthdays, commiserating over having to forgo a proper toast. Soon the clothes Cassie had passed down to Brynn for Wyatt came back to her for new son Logan, whom Rowyn, born eight months earlier, adored.

All four kids ended up in day care with their moms’ friend Jen Scharber. She would have been the one driving the boys to preschool that crisp fall day when Cassie went to pick up Wyatt, but she’d just closed her day care the month before to work as a paralegal. “I often think if I’d only kept it open,” says Scharber, now 35, “would this have ever…?”

8:18 A.M. September 16, 2014

To this day no one knows how Rowyn crawled in front of the car or under it—she’d been several feet away when Cassie last saw her. Brynn thought she was still in the house. But when the two friends realized she’d been hit, Brynn scooped her up off the gravel, and Cassie leaped out of the car and called 911. “Whoever it was asked me if she was breathing, and Brynn said she didn’t know,” Cassie says. “So I took her. That’s when I noticed all the blood on Brynn’s white robe.”

Cassie laid the limp toddler in the grass and started doing CPR, as the operator instructed, until a police officer arrived and took over. Brynn, screaming hysterically, ran inside to rouse her husband, Cody, who’d just fallen asleep after his graveyard shift as a road construction foreman. Cassie checked on the boys and told them to stay in the car.

Sheriff’s deputies, paramedics, and firefighters arrived quickly at the scene. Some continued to try to revive Rowyn while others stretched yellow tape around the circular drive as neighbors and relatives started gathering in the yard. Amid the urgent commotion, Cassie and Brynn found themselves sitting huddled on the grass, clutching each other. “We just need to pray for a miracle,” they both recall Brynn saying. And they did. They were still together when a firefighter came over and told them that Rowyn was gone. “We were just like, ‘No, no, no,’ ” Brynn remembers. “And I told Cassie right off the bat, ‘Don’t blame yourself. It’s not your fault.’”

Related Video:

Watch news, TV and more on Yahoo View.

Cassie was in her own world, her thoughts looping maniacally: I cannot have killed Rowyn. This cannot have happened. How can I fix this? I have to fix this. She could barely breathe and sat there rocking back and forth in shock as her fingers curled, clenched like claws, shaking violently. Brynn hugged her friend, still fixated on the idea that things would be OK, that somehow Rowyn’s terrifyingly still lips would break into a mischievous grin and she’d be dancing again. At some point the two women broke apart, and Brynn went to sit with Cody in the ambulance, holding their baby girl for a long, long time, crying. “I just couldn’t bear to let her go,” she says. When it was time to put her in the coroner’s truck, the truth finally started sinking in. “You’re not taking my daughter from me,” Brynn wailed.

The First Week

After Rowyn was driven away, Brynn made it to her bedroom, where she balled up in her closet, knees to her chest, terrified to close her eyes because all she would see was Rowyn’s lifeless 23-pound body. Neighbors and relatives poured in and out of the house, trying to offer solace, and someone asked Jim Ford, pastor of the New Day Christian Centre, to come by. Ford had never met the family, and when he arrived, relatives were manning the porch like bouncers, asking who he was. Before he could finish answering, Brynn opened the door. “I know you,” she said and burst into tears. “Every day I drive by and see the place where your daughter was killed.” Ford was overcome. His own 17-year-old daughter had died in a car accident four years earlier only a quarter of a mile away. “We cried and we talked,” he says. “I told her that it’s hard to see now, but one day you’ll know that things are going to be OK.”

Meanwhile, Cassie had made it home and lay in bed unable to stop sobbing. She kept repeating, “I just killed somebody’s child,” according to Scharber, who tried to comfort her. Cassie also feared the police might come for her, unaware that the sheriff’s initial report described Rowyn’s death as an accident (the final report confirmed the findings four and a half months later). Ford later reached out to Cassie too. “My heart just broke for her,” he says. “I was worried she might start to feel suicidal. All I could do was let her talk, work through it.”

As Tuesday blurred into Wednesday, then Thursday, the two moms were texting. Even though Brynn reassured her friend that she didn’t blame her, Cassie was convinced she’d change her mind; “I knew that grief has many stages,” she says.

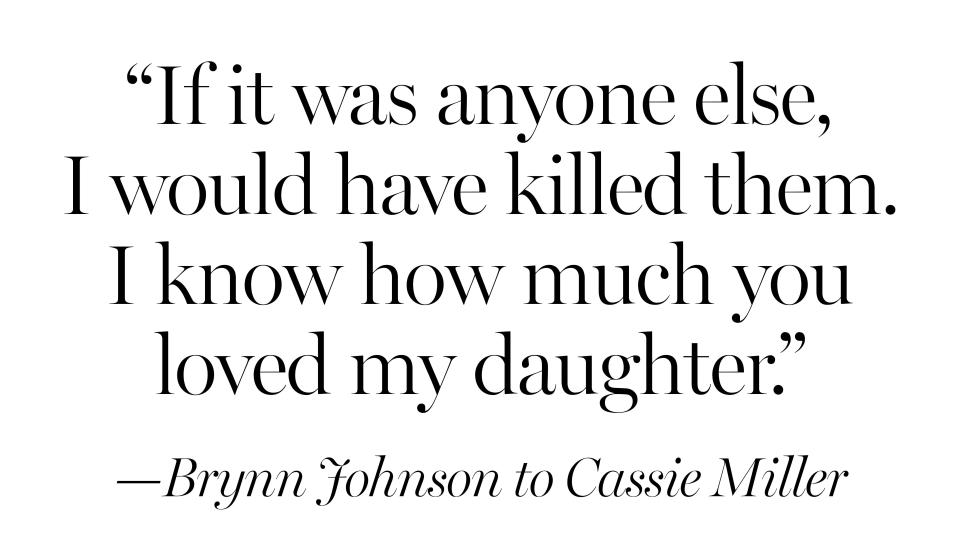

Brynn could sense Cassie’s doubt and on Friday decided to visit in person with Cody. Cassie was nervous. She made sure her car was out of the driveway so it wouldn’t traumatize them. “I didn’t want her seeing me because I felt like it would be so painful,” she says. But Brynn wasn’t having it. “I went in, took her hand, and told her, ‘I don’t understand it myself, but I love you more now than I did before. If it was anyone else, I would have gotten my gun and killed them. I’m glad it was you because I know how much you loved my daughter. It’s just a terrible, terrible accident that we both have to live with the rest of our lives. And we can get through this if we do it together.’ ”

Cody embraced her too. “It was very close. It was very comforting,” says Cassie. “I still felt like they were just in shock and would change their minds with time. But their kindness was unbelievable. There are just no words to really describe how much grace I felt at that time.”

The First Month

The morning of the funeral, Brynn spotted a red-tailed hawk through the damp fog and wondered if it was Rowyn. The sun broke through for the celebration of life that followed, where they released balloons in bright turquoise—Rowyn’s favorite color—in her honor. So many people attended, the barn where it was held couldn’t hold everyone. “It was the second hardest day of my life,” says Cassie. “Being that person, and being there….” Brynn just wanted to open the casket and hold her baby one more time.

Afterward Brynn had no idea how to get through the days. “There were times when I didn’t give a shit anymore. Like, what is there to live for? I just lost my daughter,” she recalls. Anytime Cody or Wyatt left the house, she worried: “It was like, Who’s going to go next?” And her marriage was strained. “Men and women handle grief so differently,” she says. “I was angry at the situation, and Cody was angry at someone. And probably at me too, though he didn’t say it. I mean, I blamed myself. I was standing right there. I’ve apologized over and over to my daughter: ‘Why wasn’t I holding you?’ ” Cody agrees it was tough. “I’ve never blamed her or Cassie,” he says, “but I was angry at them.”

Losing a child is unfathomably devastating, but there is a path for healing, a long tradition of mourning that Brynn learned she could lean on. Cassie, however, was in a no-man’s land. There was no Hallmark card to receive, no self-help book to read. She was reckoning with grief and trauma—and also social judgment. In the days and weeks following the service, she weathered dark thoughts. Cars were terrifying. Going over a speed bump jolted her back to the accident. “But I knew I had to start driving again,” she says. A friend helped her trade in the Highlander for another car, and after a couple of sessions of a therapy for trauma, Cassie was taking Easton to school again.

When she first spotted Brynn dropping off Wyatt, she kept to herself. She couldn’t bear the sight of her grief-stricken friend with no Rowyn bopping around in the back seat. After several days, one morning Brynn just got into Cassie’s car and said, “I’m sorry that it’s so hard for you to see me.” Brynn was frustrated, she says now: “I felt like it was equally hard for me to see her, but I was making it happen. It was like, ‘Let’s just move forward and be OK.’ I also missed the mom I could just give a hug to in the mornings and chat with after we dropped off the boys.” They slowly started doing that again. Endlessly they combed over the details of that abysmal day, trying to fill in the gaps: Where was Kimber, Brynn’s lab, who was always with Rowyn? How much did the boys see? How did Rowyn get in front of the car? They shared their pain and how hard it was watching everyone go about their normal lives. “It was like, ‘Do you not remember that my daughter just died?’ And, for Cassie, ‘Do you not remember that I just ran over my friend’s kid?’” says Brynn. “We really confided in each other and became very close.”

In one of those talks, Cassie said she’d been thinking of ways they could honor Rowyn. It was a spark: Brynn came up with the idea of covering the funeral expenses for families who’d lost children—it had been such a relief when the community did that for her. They decided to call their charity Raise for Rowyn.

Three Months After

Finding a positive way to leverage their grief gave Brynn and Cassie a path forward, and they worked furiously on their new project. But Cassie was caring for her sick grandmother, and when she passed away, it set her back; her father’s sudden death a year later was even more devastating. She’d already sought counseling, and over time she tried just about every kind of therapy—individual, marriage counseling, counseling with Easton, who’d become anxious about her well-being, the trauma sessions, and a weeklong intensive program. But nobody could truly relate to her situation. One day “in a really dark place,” Cassie says, she googled “people who accidentally killed other people” and came across a site called accidentalimpacts.org. There, for the first time, she found others like her. In post after post, people described how they’d unintentionally caused a death—driving, misfiring a gun, making a medical mistake, killing strangers, boyfriends, best friends, a one-year-old baby. Some became shut-ins, but others talked of how they’d managed to move on. “I just thought, Wow,” says Cassie. “I am not alone.”

Maryann Gray, Ph.D., a former assistant provost at UCLA, started the site in February 2014. “To my knowledge,” she says “there’s not a single professional article, or any kind of therapy protocol, theory, or research on this population. There is nothing.” Gray, who at 22 accidentally killed a little boy when he darted in front of her car, points out that when a person causes a fatality, they face a profound moral question: How can you be a good person when, now matter how unavoidably it happened, you took a life? She says that although many of the people on the site fear their lives are ruined, this kind of reckoning offers an opportunity to grow and become more compassionate. She says those in despair can, in fact, be happy again. What helps enormously, she says, “is kindness and acceptance from other people.”

Cassie doesn’t take the compassion she was shown lightly. “If Brynn and her family had blamed me,” she says, “I would likely not be alive today. I am incredibly grateful for their forgiveness, and I’m incredibly sorry for the accident. My heart and mind will struggle with this reality until the day that I die.”

A Year Later

Raise for Rowyn took off beyond anyone’s expectations. Cassie and Brynn threw their first 5K run and fund-raiser, a semiformal dinner and auction, on April 18, 2015. It seemed as if the whole town came, and they raised $60,000. “Right in the middle of the dinner,” says Scharber, who is now executive director of the nonprofit, “someone said, ‘Did you hear what happened in Marysville?’”

That morning, two hours away, a little girl not yet two years old named Alexa Rae had been accidentally run over by her father in their driveway. It was such an eerily similar story to Rowyn’s, and the family became the charity’s first official beneficiary. “Brynn and Cassie essentially paid for the whole funeral and told us to spare no expense,” says Alexa Rae’s mother, Ally Burman, who came to meet the friends in person. They stayed in contact over the next many months as Burman’s life unraveled—she split from Alexa Rae’s father and relapsed, after years of sobriety, on heroin. But today, at 27, she’s sober, in a new relationship, and expecting a baby girl. “If they hadn’t come into my life, if I hadn’t been able to see that someone had made it through this and done something good from it,” she says, breaking down, “I don’t know if I would have made it through another day. Once they wrapped their arms around me, they were with me, and they still are. They’re everything.”

Three Years Later

When Brynn is asked about her unwavering forgiveness (and she gets that question often), she has a hard time explaining what seems so natural to her. “It was obvious that Cassie would never do this on purpose,” she says. “And I feel equally to blame. I wish she was paying more attention, but I wish I had been too.” Even now, Rowyn’s loss doesn’t seem real to her.

Cassie hasn’t stopped questioning herself. She never read the final sheriff’s report (nor did Brynn) that concluded there was no way she could have seen Rowyn, her being so tiny, over the car’s tall hood. But no report or official document can change what happened. “I have replayed those moments over and over again,” she says. “I have struggled with wishing I had picked Rowyn up and handed her to Brynn before getting into the car. I still struggle when I see the clock at 8:18. My therapist used to ask me if I just wanted to punish myself for the rest of my life. And in some ways of course I should, right? But I also have to try to move forward for myself and my family.”

In an effort to start fresh, Cassie sold her house and moved everyone into a trailer while building a new home. She went from working part-time at Washington State’s Disability Determination Services to full-time again. Then, in February of last year, she made the agonizing decision to step down from the charity. It was as if she and Brynn were still in that huddle on the grass, hanging on and holding each other up, and she needed to find her own footing.

Brynn was upset at first, but she understood. She has her hands full running Raise for Rowyn and taking care of her new daughter, Mynrow, born in 2015. The two friends still see each other whenever they can, and they’re still swapping baby clothes. “Cassie just pinned a flower on one of Logan’s hats and handed it down to Mynrow,” Brynn says, laughing. “There’s never going to be a moment that I forget Rowyn—she’s very present in our home. Nor will I ever not think about Cassie. We have both experienced the most traumatic, horrific, life-changing event ever. And we overcame it together and still have remained friends. It’s a bond that you don’t have with anybody else.”

To help families who have lost a child, go to raiseforrowyn.org.