Brent Carver obituary

The Canadian actor Brent Carver, who has died aged 68, played only once in the UK, in London in 1992, but in a performance of such shattering, flamboyant intensity as Molina, a gay window dresser, that it instantly entered the pantheon of fabled musical theatre turns.

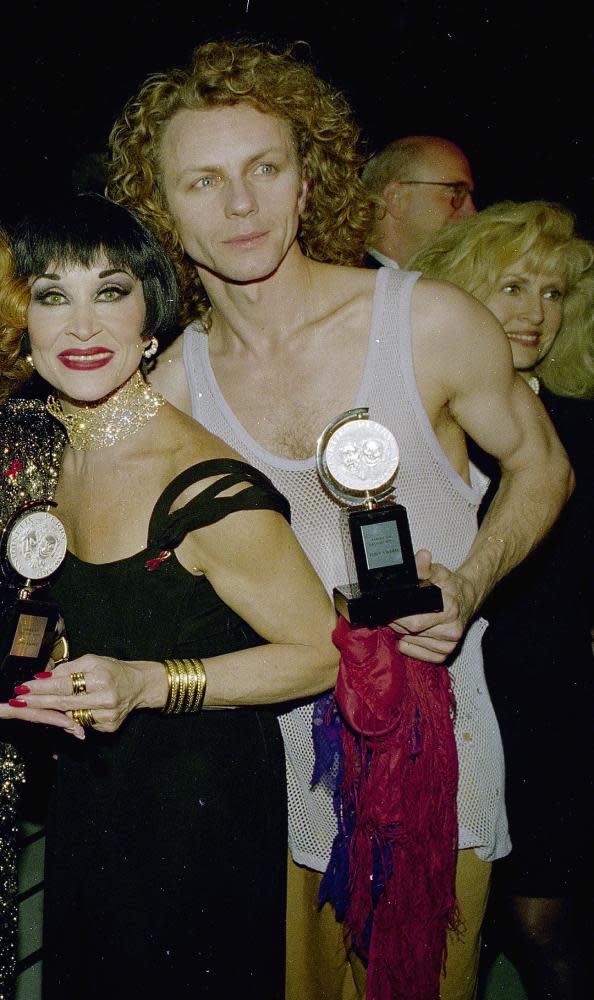

The show was John Kander and Fred Ebb’s Kiss of the Spiderwoman at the Shaftesbury theatre in the West End. When Hal Prince’s production moved to Broadway in 1993, Carver won a Tony award – the show, with a book by Terrence McNally, adapted from Manuel Puig’s 1976 novel, collected seven in all – and, at the age of 40, Carver’s career had come into focus.

He had worked for 20 years with all the leading practitioners in Toronto and Stratford, Ontario – the resident English directors John Neville and Robin Phillips, the actors Christopher Plummer, Martha Henry and Richard Monette.

And now, according to Prince, who had promoted him to the leading role he was at first understudying in Kiss of the Spider Woman’s try-out in upstate New York, after the original Molina left, he was an amazing discovery, a new superstar. The only reason he didn’t sustain that status in the public eye was because he didn’t choose to.

Carver’s seemingly ageless, bubble-haired Molina, puckish of demeanour and as wire-framed as a row of steel shirt-hangers, was incarcerated in a Latin American prison – he had been entrapped by a minor – along with a political activist, Valentin (Anthony Crivello) and his own high-flown fantasies of movie divas, especially Dolores del Rio. These were acted out on an upper level by Chita Rivera as the Spiderwoman while the two men, bound in torture, muddled their way towards an accommodation resembling something like love.

With his firm, yet flickering, face, subtle, ingratiating gestures and strong baritone voice, Carver became an expressive conduit, a waterfall, through whom the whole musical poured. Commenting on his emotional openness on stage, the critic Karen Fricker said that he was always “acutely present, in his body, and the moment”. And yet just three months after winning the Tony, he left the show.

At the time of Spiderwoman on Broadway, Carver contested the actor’s usual defence of losing oneself in a character by telling the New York Times that he felt allowed to be more of himself on stage than he was off it: “Your life doesn’t stop for two hours and 20 minutes while you are playing a character. You’re very much more alive as yourself.”

Broadway? He could take it or leave it. He liked staying at home – for many years, a cottage in Niagara-on-the Lake, Ontario – and he liked living in Canada. Five years later, in 1998, Prince insisted that he be cast in the Lincoln Center production of Jason Robert Brown’s Parade, another great fable of social and political injustice, this time based on the true life story of a Jewish factory manager, Leo Frank, wrongly convicted in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1913, of a young girl’s murder on the grounds that he was the last person to see her alive.

The librettist, Alfred Uhry, thought Prince was mad to think of Carver, blond and blue-eyed, and 15 years older than the character, as a good idea, but Prince had his way and Carver won everyone over, including a rhapsodic Uhry. The twist in the tale – its irony increases every day – was that after Frank was revealed as clearly innocent, he was dragged from prison and lynched by an antisemitic mob.

Parade, which had a sensational opening number and a score rippling with undertones of Sondheim at his most anthemic and Charles Ives at his most gallantly patriotic, never moved downtown to Broadway, though Carver was nominated for a second Tony (he didn’t win). The London premiere, nearly 20 years later, was at the Donmar Warehouse with an actor of an uncannily similar nomenclature – Bertie Carvel – giving a superb performance as Frank.

The only other big new musical Carver was associated with was a misguided Lord of the Rings (2006), directed in Toronto by the British Matthew Warchus, now artistic director of the Old Vic. Carver played Gandalf, but had trouble with the narrative, deciding to just clarify and deliver, with no room for anything as “deep” as Ian McKellen achieved in the Peter Jackson films. When the musical opened at Drury Lane in London in 2007 (with Malcolm Storry as Gandalf), it was the most expensive (£25m) musical in West End history, and though it flopped financially, it somehow struggled on for just over a year’s run.

Brent was born of Welsh and Irish antecedents in Cranbrook, a small town in the Rockies of British Columbia, the third of eight children (one drowned accidentally, aged two) of Kenneth Carver, a lumber truck driver, and his wife Lois (nee Wills), a clerk and sometime waitress. He studied drama at the University of British Columbia (1969-72) in Vancouver and started out on the stage at the Arts Club in that city.

In 1980 he began a long association with the Stratford festival in Ontario, playing the febrile younger son in Long Day’s Journey Into Night with William Hutt and Martha Henry, and one of the two imprisoned gay men in Dachau in Martin Sherman’s Bent, shortly after the play was premiered in London with McKellen.

He played Hamlet in 1986 and, just before Spiderwoman, the lead in Unidentified Human Remains and the True Nature of Love by one of the most brilliant and provocative new Canadian playwrights, Brad Fraser.

Much less predictably, he played Tevye the milkman in Fiddler on the Roof at Canada’s Stratford in 2000. And in 2004 he was possibly the first ever 50-year-old Edgar in King Lear, opposite Plummer, directed by Jonathan Miller at Lincoln Center. Other Shakespearean roles at the Stratford festival included Jaques in As You Like It, Friar Laurence in Romeo and Juliet (Orlando Bloom was Romeo), Cyrano de Bergerac and Feste in Twelfth Night.

He had began his television career in a 1978 summer series, Leo and Me, co-starring a 15-year-old Michael J Fox, and went on to make several big Canadian TV series, including The Twilight Zone (1989) and the first series of Street Legal, about life in a Canadian law firm.

His movies included Shadow Dancing (1988), a thriller with Plummer; the sci-fi Millennium (1989), with Kris Kristofferson and Cheryl Ladd; and Atom Egoyan’s Ararat (2002), with Charles Aznavour and Plummer, in the first movie to deal with the Armenian genocide continuing after the first world war.

Carver may well be remembered as a one-show wonder, but in his own quiet, softly spoken way, he was a trailblazer, both in the repertoire and in new plays, for moving the social outsider centre stage – he did this time and time again in his choices. He once defined, without pomposity, the three basic requirements for good acting: courage, confidence and compassion.

His death was announced by his family but no cause was given. Two sisters, Vicki and Frankie, and two brothers, Randy and Shawn, survive him.

• Brent Christopher Carver, actor, born 17 November 1951; died 4 August 2020