A Brief History of Presidential Illnesses

Donald Trump recently became one of the more than 7 million people in the United States to be have contracted COVID-19. And while the news of his diagnosis has sparked a flurry of attention, it's hardly the first time that a sitting president has suffered from a serious medical malady. In fact, of the 44 people who have held the country's chief office, far more of them have suffered from some form of sickness while in office than have remained completely healthy. Here, a far-from-exhaustive list of some of the most prominent medical issues to see the inside of the Oval Office.

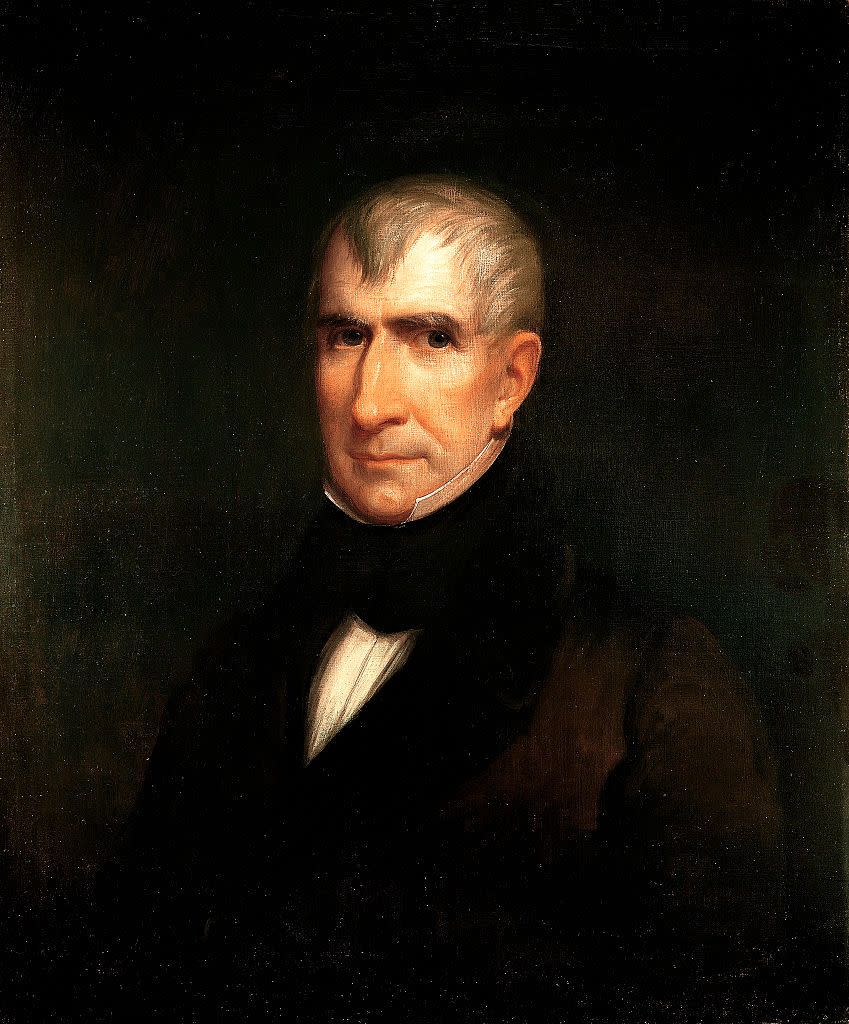

William Henry Harrison

Serving the shortest tenure as President in U.S. history, Harrison died a mere 32 days after taking office as the result of a fatal illness. The 68-year-old former soldier, who gained fame by leading troops in The Battle of Tippecanoe, was inaugurated on March 4, 1841, and went on to give the longest inaugural address to date. His 8,445 word-speech went on for nearly two hours on a cold, windy day, and he wore with no hat or coat. Harrison fell ill later that month, developing a fever and what was then diagnosed as pneumonia. He died from complications of the illness on April 5, 1841, and the legend that he died due to his prolonged inauguration address has persisted ever since, though some modern scholars have posited that the deadly disease may in fact have been typhoid fever from Washington D.C.'s contaminated water supply.

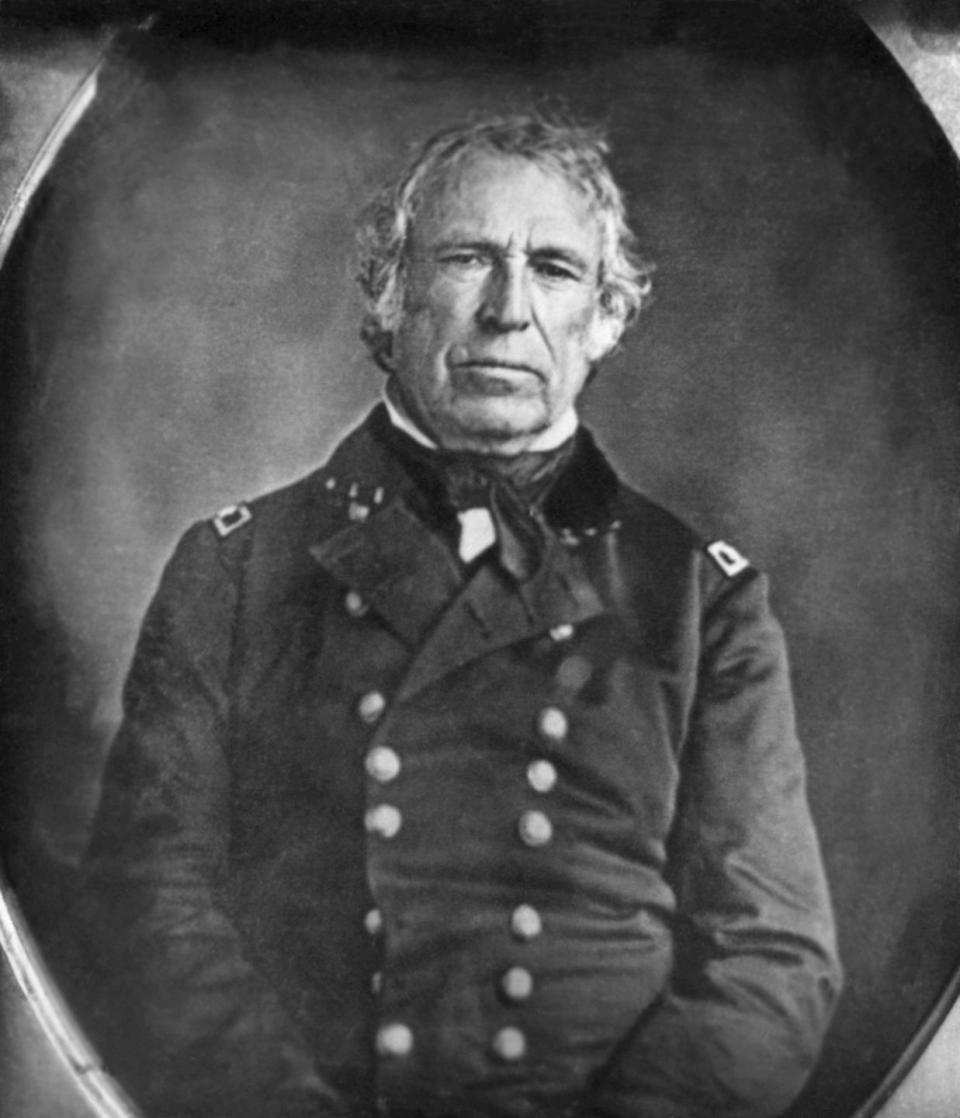

Zachary Taylor

Another short-lived presidential run, Taylor survived 16 months in office before succumbing to a sudden illness on July 9, 1850. His doctors at the time diagnosed him with cholera—possibly as a result of that same tainted water which may have done in Harrison a decade before—but historians have posited everything from gastroenteritis to heat stroke to arsenic poisoning. (A 2014 tissue tests determined the latter was not the case.)

James Garfield

While an assassin's bullet ultimately led to our 20th president's death, it was likely his doctors who really did him in. On July 2, 1881, Charles Guiteau, a mentally ill lawyer and writer, shot Garfield twice—one grazing shot, and a second, which lodged in his abdomen. Garfield was awake and alert following the attempt, and was rushed into medical care where a gunshot expert named Dr. Doctor Willard Bliss (yes, his first name was Doctor) took over his care. Concerned with removing the remaining bullet, Garfield's physicians probed the wound with their unwashed fingers (such practices were common at the time when germ theory was not widely accepted) and then undertook weeks of arduous attempts to locate the bullet including using Alexander Graham Bell's newly invented metal detector as well as exploratory surgery, which widened the 3-inch wound to the full length of Garfield's abdomen. Though the president remained conscious, he developed a massive infection, living in constant pain before finally succumbing on September 19.

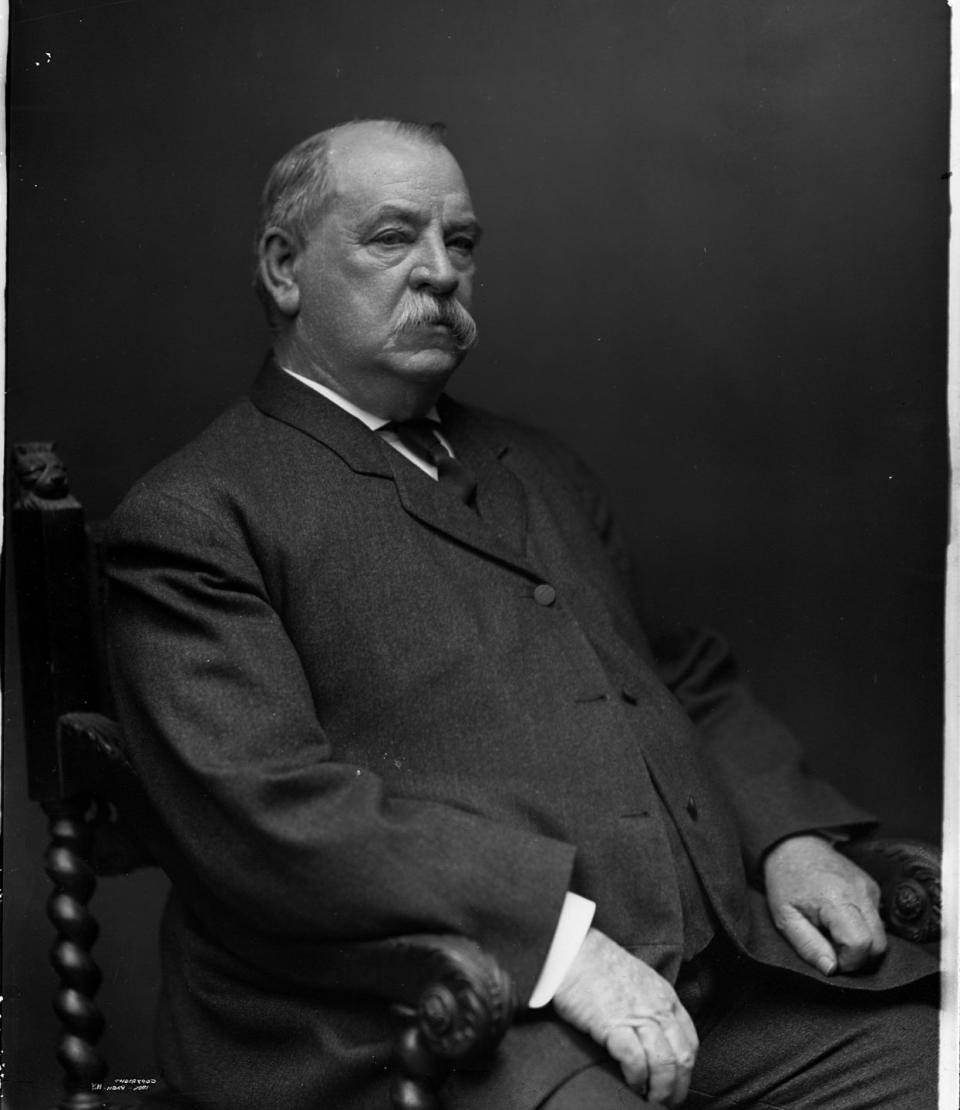

Grover Cleveland

Just months after Cleveland took office for his second term in 1893, he was diagnosed with a cancerous tumor on the roof of his mouth. Fearing what the news of his illness would do to the country and the economy, Cleveland announced that he would be taking his friend's yacht out on a four day fishing trip as a cover for possibly the most daring secret surgery in presidential history. Over the course of just an hour and a half aboard the yacht, a team of surgeons removed the tumor along with several of the president's teeth and a large part of his upper left jawbone.

Cleveland relied on his trademark mustache to cover all evidence of the surgery and was largely successful—though news leaked in the months after the operation, Cleveland denied the accusations and smeared the name of the doctor who had revealed it publicly. It wasn't until 24 years after the surgery, when Cleveland himself was dead, that another of the surgeons finally corroborated the story.

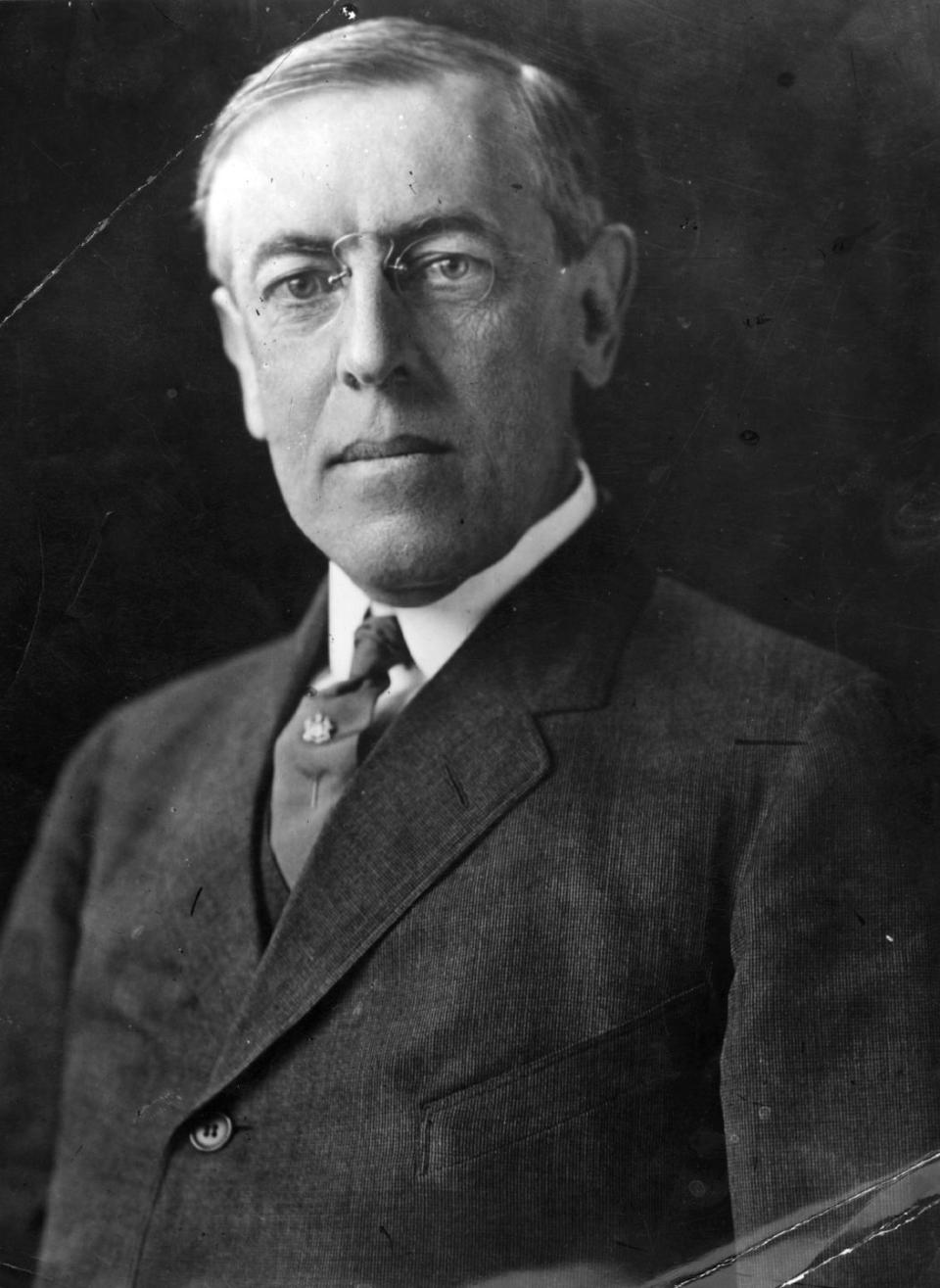

Woodrow Wilson

Woodrow Wilson led America through the first World War and would develop a reputation as one of the country's most relentless politicians, but his battles with his own body remained largely hidden from the public. Considered by some to be a hypochondriac, Wilson suffered lifelong gastrointestinal issues and indigestion, even using a stomach pump on himself throughout his presidency to seek relief. A possible hemorrhage left him with a severe vision deficit during his time as a professor and university president at Princeton and chronic hypertension contributed to what medical historians have posited could be as many as half a dozen small strokes before he took on the governorship of New Jersey in 1910. As early as his presidential inauguration in 1913, famed physician Silas Weir Mitchell predicted that he would never complete his first term.

According to the notes of Wilson's White House doctor Cary T. Grayson, in the summer of 1918, about six months before he would head to Paris to help negotiate the Treaty of Versailles, Wilson underwent a secretive treatment for a breathing issue—what is now suspected to be surgery to remove nasal polyps. Evidently only the doctor himself, a nurse, the president's wife Edith, and a White House usher were aware of the treatment.

During his time in Paris, Wilson worked constantly, removing all exercise and relaxation time from his schedule. That April he fell ill—possibly with influenza, which was still ravaging Europe from the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic, though some have suggested that the flu was just a cover for another stroke. After returning to the U.S. in July and finding the Senate unwilling to accept his treaty, Wilson took on a nationwide train tour to advocate his version of the treaty to the public, but the stress may have proved too much. On September 25, 1919, Wilson complain of a headache and his wife Edith later found him with his facial muscles twitching uncontrollably. The tour was canceled and Wilson returned to Washington, but on October 2 his condition worsened.

That day, Wilson apparently suffered from a massive stroke. (Reports have conflicted over the years as to whether he woke with paralysis or was found to have collapsed.) Grayson later found him to be paralyzed along his left side and blind in his right eye. The president went into seclusion for the remainder of his term, but his condition was kept a closely guarded secret.

At the time, there were no clear legal parameters of what to do—the Constitution only stipulated that the Vice President could assume presidential power in the case that the president's "death, resignation, or inability to discharge the duties of said office" and Wilson was neither dead nor willing to resign or stipulate his inability to discharge his duties. In place of Vice President Thomas Marshall, Edith Wilson took over what she would later call "stewardship" of the nation's highest office. Though she insisted throughout her life that Wilson made all of the decisions during that time and she simply ferried information, modern scholars have found it clear that Edith's role was far greater and that she was, functionally, the country's chief executive until the end of Wilson's term in 1921, all without the knowledge of the American public.

Warren G Harding

On August 2, 1923, Harding became the sixth president to die in office, but he had long been an ill man. For years he had suffered from a nervous condition known at the time as neurasthenia (characterized by physical and mental exhaustion). Since at least 1918, he had dealt with an enlarged heart, chest pain, and difficulty sleeping which could, to the modern eye, indicate congestive heart disease. Leading up to his death, he had complained of cramps, fever, shortness of breath, and indigestion, but his death came on suddenly on a quiet evening in the presidential suite of San Francisco’s Palace Hotel as his wife read him the Saturday Evening Post.

The night of his death, then-Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover sent out the official news that the president had died of “a stroke of cerebral apoplexy,” but it now seems most likely that Harding instead suffered a sudden heart attack.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Perhaps the most famous presidential secret sufferer, FDR now-famously lived most of his adult life with the effects of polio, relying on a wheelchair of mobility. Unlike most polio sufferers, who typically contract the illness as very young children, FDR developed the disease at the exceptionally unusual age of 39. Though it is not entirely clear when and where he caught polio, the effects became apparent during the summer of 1921 when he was visiting his family's Campobello Island cottage in New Brunswick, Canada. Over the course of several days, the future president developed lower back pain and weakness in his legs as well as extreme skin sensitivity. After some conflicting medical advice, he was eventually diagnosed with infantile paralysis aka polio by an expert and spent the next several years in rehabilitation, retreating from his political career.

Though he never regained the ability to walk, Roosevelt did return to politics in the mid-1920s, ultimately winning the governorship of New York in 1928 and later the presidency in 1932.

While his disability was not entirely a secret, FDR did work to disguise his mobility issues in public, adapting his own, more discreet and maneuverable version of a wheelchair out of a dining chair and devising a method of appearing to walk at political events using a cane and the assistance of someone's arm as he moved his hips and legs to give the impression of walking. During his presidency, the press were requested not to photograph FDR while walking or maneuvering in and out of cars, and the Secret Service were charged with preventing the taking of photographs that might show the president in a “disabled or weak” state.

FDR died during his fourth term in office of a cerebral hemorrhage on April 12, 1945.

Throughout his life, he also worked to raise funds for the Georgia Warm Springs Foundation, a premiere destination for aquatherapy and rehabilitation for polio sufferers, as well as establishing the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, the fundraising efforts for which would later become known as the March of Dimes. Those funds would eventually go on to help fund the research of Jonas Salk, the scientist who developed the polio vaccine in 1953.

John F. Kennedy

Most of us think of JFK as a hale and hearty New England sporting sort, but in reality, it appears that our 35th president dealt with a variety of health issues throughout his life, and by the time he took office dealt with near-constant pain. "There was hardly a day that went by that he didn't suffer terribly," said Robert Dallek, presidential historian and author of An Unfinished Life: John F. Kennedy, 1917-1963 who was granted access to Kennedy's X-rays and prescription drug records from 1955 to the end of his life. Among his myriad lifelong ailments, Kennedy suffered from colitis, Addison's disease (a hormonal disorder, symptoms of which include abdominal and joint pain, fatigue, low blood sugar, and gastrointestinal problems) and osteoporosis in his lower back which caused him extreme pain and led to multiple surgeries. (His famous book, Profiles in Courage, was written in 1954 while recovering from a near-deadly back surgery.) To combat the symptoms, Kennedy took as many as a dozen different medications simultaneously, according to Dallek's research.

Throughout his political career, JFK and his team went to great lengths to hide his medical issues for fear that they would hurt the public perception of him. In 1960, during the race for the Democratic nomination, Lyndon B. Johnson's aides leaked Kennedy's Addison's diagnosis to the press; Kennedy's camp flatly denied it.

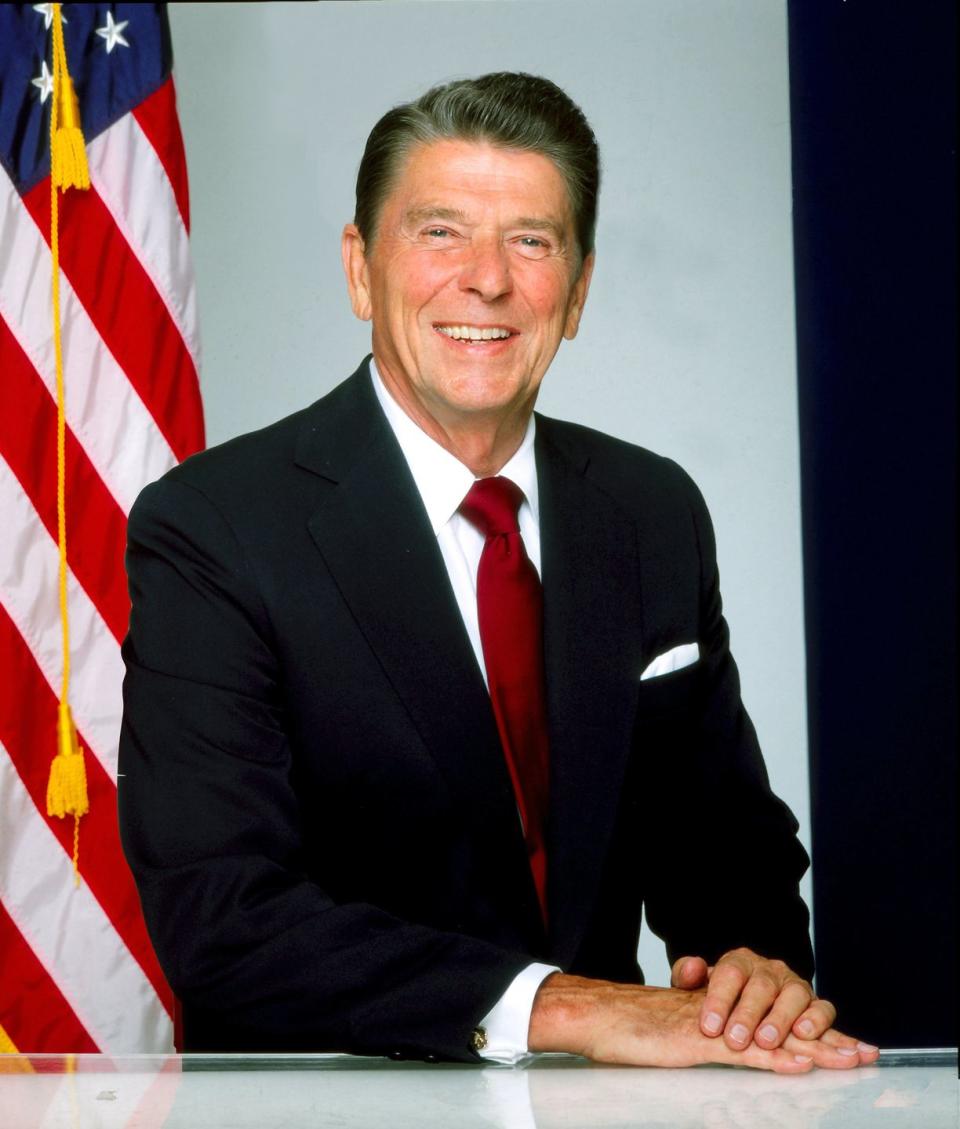

Ronald Reagan

Though Reagan was at the time the nation's oldest serving president, he was in relatively good health until a routine colonoscopy in 1985 revealed a polyp in his large intestine. Doctors were able to remove the polyp along with two feet of lower intestine that summer. Later in that year he also had a surgery to remove skin cancer on his nose—he would have a similar operation in 1987.

In 1994, four years after the end of his presidency, Reagan was diagnosed with Alzheimer's Disease. While analysis of his speech patterns during his presidency has suggested there were possible signs of the disease during his time in office, there is no way to know definitively.

You Might Also Like