The Brilliant Abyss by Helen Scales; Below the Edge of Darkness by Edith Widder – reviews

Divers investigating an underwater canyon off California made a startling discovery in 2002. They found a dead whale that appeared to be wrapped in a crimson, shag-pile carpet. Closer examination revealed this covering was made of red worms, previously unknown to science, which were eating the whale’s skeleton.

Subsequent research showed these acid-secreting creatures were all female and inside each was a tube containing a harem of dwarf males. These were carried around to provide fertilisation when the worms encountered food, such as a whale carcass, and wanted to start breeding. Scientists named the new genus Osedax, which means “bone-devourer”.

Were there more such bone-devourers? they wondered. Answers came swiftly. In waters off Sweden, they discovered Osedax mucofloris – literally “bone-eating snot flowers” – while the species Osedax jabba was named because its plump trunk reminded scientists of Jabba the Hutt from Star Wars. “The oceans, it turns out, are full of bone-eating worms… though nobody yet knows how they move through the deep sea or how they locate a skeleton,” writes British marine biologist Helen Scales.

Despite their ubiquity, Osedax’s abyssal home allowed them to evade human detection for millennia, suggesting many other equally bizarre lifeforms lurk in the ocean depths, a point stressed by both Scales and US oceanographer Edith Widder. In their separate, equally vivid accounts of ocean life, they outline some of the staggering biological treasures that have already been uncovered – with the promise that many more await discovery.

Consider the example of the cockeyed squid. “Its left eye is giant and directed upwards toward the sunlight while the right eye is smaller and aimed downward into the inky depths,” writes Widder. It sounds nonsensical until you learn the smaller eye is encircled with bioluminescent light organs. “Thus the large eye hunts overhead for dim, distant silhouettes of prey while the bottom eye can use its built-in flashlights to illuminate more proximate prey.”

Bioluminescence turns out to be critical to abyssal life, adds Widder. Creatures from giant squid to plankton emit light to attract mates and food. “There are shrimps that can spew intense streams of liquid light from their mouths, like fire-breathing dragons; squid that discharge photon torpedoes of blinding blue brilliance; and fish that can eject sparkling dust storms out of a tube on each shoulder,” she reveals.

Far from being a dark, dead zone, as once thought, the abyss glitters with light and life and could house up to 30m different species, according to one estimate. Nor should we be surprised by this number. “More than 95% of the Earth’s biosphere is made up of deep sea,” says Scales.

Both scientists have produced stylish, eloquent works, with Widder’s being the more personal, beginning with her account of an adolescent illness that nearly left her blind and then moving to her current position as a world expert on underwater light communication. “My obsession with bioluminescence grew out of my brush with blindness,” she writes.

In pursuing this fascination, Widder has been given a unique view of the denizens of the deep, from the unassuming bioluminescent bristlemouth fish, which turns out to be Earth’s most abundant vertebrate, to the Pacific barreleye fish, which can rotate telescope eyes inside its transparent skull.

Scales’s approach is slightly less personal but is equally enthralling and richly expressed and highlights how closely our lives depend on the deep. As she points out, the oceans have taken up more than 90% of the extra heat trapped by human-emitted carbon dioxide since preindustrial times. Without our seas, Earth would be scorched. But as she adds, the abyss, unlike that other great distant realm, outer space, has no stars at night to remind us it is there. “Yet the deep, quite simply, makes this planet habitable.”

But for how long can we rely on this protection? Humanity is adding acids, toxins, plastics and heat to the oceans while vacuuming up its fish stocks at an alarming rate. “We are managing to destroy the ocean before we even know what is in it,” writes Widder.

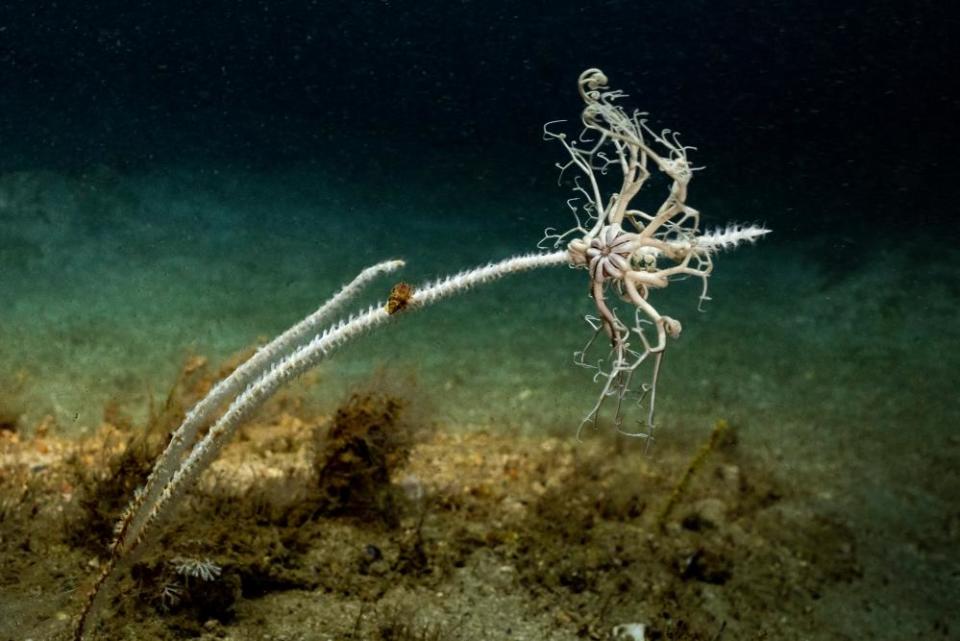

On top of these woes, a new crisis looms. To provide the rare metals needed to build wind turbines and electric cars for our climate-friendly future, mining companies are now eyeing up the mineral-rich nodules that litter the ocean bed. Enormous, remotely operated electric bulldozers are being designed to crawl the seafloor and sweep up these minerals, trampling all life and kicking up fine, muddy clouds that would hang in the water for aeons, writes Scales. “Delicate animals caught in those clouds and unable to swim away, like corals and sponges, would be smothered and choked.”

It is a chilling prospect. The deep is our planet’s last wild place and we despoil it at our peril. To their credit, Widder and Scales have made abundantly, yet entertainingly clear the nature of the dangers that lie ahead.

• The Brilliant Abyss by Helen Scales is published by Bloomsbury Sigma (£16.99). To support the Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply

• Below the Edge of Darkness by Edith Widder is published by Virago (£20). To support the Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply