California police officer killed a person while driving 121 mph. DA declines to file charges

Stanislaus County sheriff’s Deputy Eric Fulmer was driving 121 mph as he approached a T-intersection on a foggy morning in January 2022.

At about the same time, a Chevrolet Camaro pulled into the intersection. Fulmer braked, but it was too late. His vehicle slammed into the side of the Camaro at nearly 90 mph, killing 21-year-old Saul Betancourt.

Following a nearly yearlong investigation, California Highway Patrol investigators have determined Fulmer’s actions were the primary cause of the collision. He was “driving at a speed which was unsafe due to the traffic conditions and limited visibility.”

Betancourt’s action, rolling the stop at the intersection where Fulmer had the right-of-way, was an associated factor in the collision, according to the CHP.

The agency’s 158-page report, obtained by The Modeseto Bee through a public records request, was submitted to the Stanislaus County District Attorney’s Office in December for consideration of misdemeanor or felony vehicular manslaughter charges against Fulmer.

In January, on the one-year anniversary of the fatal crash and the deadline for his office to pursue a misdemeanor charge, District Attorney Jeff Laugero sent a memo to the CHP and the Sheriff’s Office saying he would not charge Fulmer. The elements of the crime “are not met beyond the reasonable doubt standard,” it said.

Fulmer is on paid administrative leave and there is an active internal affairs investigation regarding the crash.

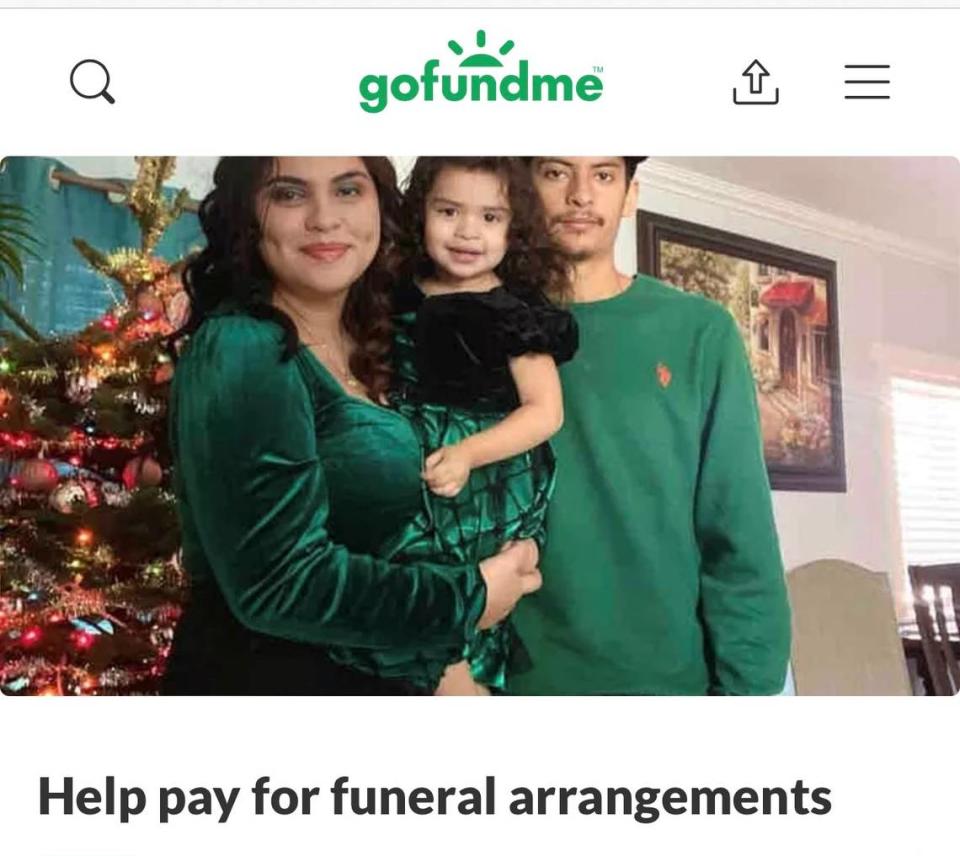

Meanwhile, Betancourt’s parents and his girlfriend, on behalf of herself and the young daughter she shared with Betancourt, filed a lawsuit against Fulmer and the Stanislaus County Sheriff’s Office in September for wrongful death and negligence.

Modesto man killed in crash involving deputy was father of 2-year-old

Fulmer, the same day the memo was sent by the DA, countersued Betancourt’s estate for negligence and personal injuries and damage.

The crash

Fulmer was a detective assigned to the city of Patterson, but on the morning of the crash, Sunday, Jan. 9, 2022, he had just finished working a 12-hour overtime shift on patrol, which ended at 7 a.m.

Maria Prado also ended her graveyard shift at 7 a.m. She and her cousin worked at a nursing home in Newman and took the same route home to Modesto. Betancourt, Prado’s boyfriend, picked her up that morning and Prado’s cousin was driving behind them, according to the CHP report.

As a detective, Fulmer drove a department-issued Nissan Maxima that was equipped with lights and sirens. He was in the Nissan on his way home to Turlock when, at 7:07 a.m., he heard deputies from the main office in Modesto dispatched to help a Newman police officer who was in a physical fight with a suspect and was not responding on his radio.

Fulmer was between Patterson and Turlock, in the area of West Main and Central avenues, and knew he was closer, so he activated the Nissan’s lights and sirens and notified dispatch that he would respond, according to the CHP report. He turned around and headed south on Crows Landing Road.

At 7:11 a.m. a dispatcher broadcast over the radio that police from Gustine, which is less than five miles from Newman, also were responding.

Fulmer got on the radio, acknowledged the dispatch and broadcast his location at Crows Landing and River Road, more than eight miles from Newman. He would later tell CHP investigators he vaguely remembers acknowledging the radio traffic but doesn’t remember what the dispatcher said.

He continued south on River Road toward Villa Manucha Road.

Betancourt and Prado were traveling east on Villa Manucha, preparing to turn north onto River Road.

Information extracted from the event data recorders in the Chevrolet and the Nissan showed how the vehicles were operated during the five seconds leading up to the crash at the intersection, according to the CHP report.

Fulmer was driving 118 mph five seconds before impact, then accelerated to 121 mph 2.5 seconds prior to the crash.

Betancourt was driving 26 mph and braking, slowing down as he approached the stop sign. He’d slowed to 6 mph when he drove across the limit line.

“At the same time, (Fulmer’s Nissan) was approximately 392 feet away and most likely not visible to Betancourt,” according to the CHP report.

He continued into the southbound lane and braked a half a second before the Chevrolet was hit.

Fulmer braked 1.5 seconds before impact and turned slightly to the right but couldn’t avoid the Chevrolet and broadsided it at 90 mph.

It was about 7:13 a.m. and still twilight, about five minutes before sunrise.

Betancourt died at the scene from injuries to his head, neck, torso and limbs, including laceration to his liver and spleen and fractures to his pelvis and left femur. His cause of death was listed as blunt injuries, according to the CHP report.

Prado’s injuries included a fractured hip, injuries to her colon and a severe concussion, family members previously told The Bee.

She and Betancourt were wearing their seat belts.

Fulmer, who was not wearing a seat belt, suffered a severe concussion, a broken femur and chest and back pain, among other injuries.

A foggy morning

There’s no question it was foggy and visibility was limited at the time of the crash, but how limited it was varied among witness statements and the CHP’s analysis, which used body camera video from an officer who responded to the scene.

An off-duty sheriff’s sergeant told CHP investigators he was driving on Crows Landing Road and saw Fulmer’s vehicle just before it turned onto River Road. He estimated visibility was “less than 1/4 mile,” or 1,320 feet.

Fulmer in his interview with investigators said it was foggy when he started responding to the call and acknowledged it became “a little bit foggier” as he turned onto Crows Landing Road. He estimated visibility at 1,000 feet.

Prado’s cousin estimated visibility was 540 feet, based on the location of a vehicle pointed to as a reference point when interviewed by a CHP officer a few hours after the crash.

CHP investigators estimated visibility was between 350 and 425 feet. Their estimate was based on video of the scene about 19 minutes after the crash. The video was taken from an officer’s body camera and the video recording system on his patrol vehicle. Measurements were derived from instruments used to survey the scene.

Using crash reconstruction software, CHP investigators calculated that a safe speed for the limited visibility would have been 64 to 72 mph.

The CHP investigation concluded, “Deputy Fulmer was determined to be the primary cause of this crash by driving at a speed which was unsafe due to the traffic conditions and limited visibility in the area of River Road and Villa Manucha Road.”

During an interview with The Bee on Monday, District Attorney Laugero said, “We aren’t confident that we could ever prove what those conditions were at the time of the collision.”

For a defendant to be convicted of vehicular manslaughter, the prosecution must prove that the person committed a misdemeanor or infraction while driving, that their actions were dangerous to human life and that those actions were committed with regular or gross negligence.

Authorized emergency vehicles are exempt from certain vehicle code laws, like speeding, when they are being used to respond to an emergency call. But the law states that the driver is not relieved of “the duty to drive with due regard for the safety of all persons using the highway, nor protect him from the consequences of an arbitrary exercise of the privileges.”

‘We are not trying to shift blame’

Asked if 121 mph was with due regard for public safety, Laugero said the emergency vehicle exemption law does not give a standard for what constitutes a safe speed. He said the weather conditions at the time of the crash are “speculative at best” because the CHP’s visibility analysis was done 19 minutes after the crash and was contradicted by statements from Fulmer and the off-duty sergeant, who told investigators Fulmer’s speed was “not excessive.”

Laugero said the sergeant would become a “critical witness” if the case went to trial.

“So right there, there is a very difficult discrepancy to overcome,” he said. “And if there is an interpretation that benefits the defense, then the jury is instructed to go with that interpretation.”

Further, the defense would point to Betancourt rolling the stop sign then stopping in the intersection in front of Fulmer.

The defense could also bring up Fulmer’s state of mind as he’s driving to Newman and Betancourt’s driving history, Laugero said.

Fulmer told CHP investigators he was working and responded to Newman the night Cpl. Ronil Singh was shot to death during a traffic stop in 2018.

“So what was going through my head, ‘like oh, God, here we go again,’” Fulmer told the CHP investigator. “So my main concern was, you know, getting there safely, I believed I was the first person that was going to be there, and to help him out.”

Fatal crash update: Deputy was responding to fight between Newman officer, suspect

As for Betancourt’s driving record, he was unlicensed at the time of the crash and had a prior conviction for driving without a license, Laugero said.

“We are not trying to shift blame, we just have to look at this realistically. What is the defense going to do with this case?” he said. “When you start to look at all of these factors, especially with the highest burden of proof beyond a reasonable doubt … we just did not believe we could ever overcome that burden.”

His office is responsible only for determining criminal liability, not civil liability or any Sheriff’s Office policy violations.

The three civil cases were consolidated last month and a case management conference is set for May.

The Bee sent emails to lawyers for all the plaintiffs and the defendants.

Prado’s attorney, Paul Kiesel, a partner at Kiesel Law LLP in Beverly Hills, said, “The conclusion not to prosecute is both shocking and baffling.” He referenced the findings in the CHP report but declined to comment further.

County Counsel Tom Boze said he cannot comment on pending litigation, and the other attorneys did not respond to requests for comment.

Following his release from the hospital, Fulmer returned to work for a period of time but was later put on paid administrative leave, according to Sheriff’s Department spokesman Sgt. Erich Layton.

He said he could not say when or why Fulmer was on put on leave.

The Stanislaus County Sheriff’s Department policy on code-3 driving, with lights and sirens on for an emergency response, reads much like the law. “Responding with emergency light(s) and siren does not relieve the deputy of the duty to continue to drive with due regard for the safety of all persons,” it says.

It says, “Deputies shall reduce speed at all street intersections” and “check each lane of the intersection to make sure it is safe to proceed” at any uncontrolled intersection.

There are other factors in the policy like how many deputies should respond to an emergency call, usually only two; who needs to be notified of and authorize a code-3 response; and the type of situations that warrant a code-3 response.