Chinese Philanthropists on Ending Climate Change

“Xing dong! Xing dong! Xing dong!” (Mandarin for “Action! Action! Action!”) is one refrain wafting on the Hawaiian breeze. The other is “Collaborate! Collaborate! Collaborate!”

Laurance S. Rockefeller, the American philanthropist and conservationist, would have been intrigued by the meeting taking place this past January in a ballroom of the Mauna Kea Beach Hotel, which he built on the Big Island of Hawaii in 1965. On the one hand, the appurtenances suggest just another blah-blah conference: podium, screen, cookies, coffee. On the other, a new day seems to be dawning.

Strewn on the long tables are Chinese-made Huawei tablets and headphones with two channels for simultaneous translation, from Mandarin to English and vice versa. Seated at the tables are 80 participants in the fourth annual East-West Philanthropists Summit, an offshoot of the East-West Center, an independent nonprofit established by Congress in 1960 to foster better understanding among the United States, Asia, and the Pacific Islands. (“A meeting place,” as Lyndon Johnson put it, “for intellectuals of the East and West.”)

In attendance are mostly top philanthropists from the United States and China, here to address together one of the world’s most pressing problems: climate change, and how to avert it through conservation and sustainability. The organizations representing the U.S. are legatees of more than 100 years of philanthropic tradition (think Rockefellers, Carnegies, Mellons), and their names are more or less instantly recognizable: the foundations of Bill and Melinda Gates, Barack Obama, Leonardo DiCaprio, and about a dozen others. The Nature Conservancy is also here, as is the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the only environmental group in the world with official observer status at the UN.

The names of the Chinese attendees, members of the country’s new class of the philanthropically inclined ultrarich, are less familiar. In fact, unless you’re a regular reader of the South China Morning Post or People’s Daily or the global “rich lists” published by Forbes and the Hurun Report, Niu Gensheng, Wang Shi, Dong Fangjun, Lu Dezhi, and He Qiaonyu are likely to be Greek to you.

But no matter. There is a can-do electricity in the conference room and in the hotel’s restaurants and terraces, a transcultural bonhomie even, that is palpable as soon as I arrive. (This at a time when, on the governmental level, all one hears is saber rattling.) “We are hoping for some magic to happen,” says Mark McGuffie, IUCN’s affable private philanthropy officer, who is one of the key behind-the-scenes players here, before the first night’s speeches. “We are in an urgent crisis. This meeting is about pulling all our resources together: the brightest minds, the passion, the funding. He Qiaonyu…”

He is about to say something about one of the two Chinese chairs of the summit, who last October at an IUCN conference in Monaco (where I first met her) stunned the international environmental community by pledging $1.5 billion to conservation-the amount as stunning as its source. Then he thinks the better of it.

“Let’s just say,” he says with a smile, “that there have been many conversations.”

Niu Gensheng, the summit’s other chair, is an energetic man of 60 who exudes confidence in a pale blue short-sleeve shirt. From the podium he kicks things off: “Climate change is the greatest threat to our lives.” Then he throws down the gauntlet. A PowerPoint presentation behind him shows the planet earth underscored by a red line: “The earth must be reforested!” he proclaims. Another slide shows the sky underscored by a dark blue line: “Emissions must be stopped!” And to do this: “The East and the West should meet like a lady and a gentleman!”

His is not the usual way of stating things at conservation conferences, nor is his delivery: loud, guttural Mandarin that renders almost inaudible the delicate female voice of the translator in my earphones. But they get attention. As do his bluntly stated bona fides: “My family is the number one philanthropic family in China.” By all accounts it is, though at the start of his life no one would have pegged Niu Gensheng as someone most likely to succeed. Born in the province of Inner Mongolia, he was sold as an infant by his impoverished parents to a more prosperous family in a neighboring village for 50 renminbi-the equivalent of $7. That was in 1958. But in 2004, already a dairy mogul, he established the Lao Niu Foundation, China’s first private philanthropic entity. (That’s how recent a phenomenon philanthropy, as opposed to traditional charity, is in China. Wealth did not start accumulating in private hands until the early 1980s, when Mao Zedong’s successor, Deng Xiaoping, opened the country’s economy to market forces and began encouraging entrepreneurship-in effect making it possible for people to get rich.)

Niu endowed his foundation by taking the unprecedented step of putting into it all of his and his family’s shares in his company, China Mengniu Dairy. (“Even Gates,” he said in an interview with the Financial Times, “told me I was ahead of him.”) Since then Niu has directed $1.6 billion to 280 projects. Many have been in China: supporting early childhood education, reforesting swaths of desertifying Inner Mongolia (with 40 million trees), and partnering with the Paulson Institute to restore coastal wetlands, habitats of migratory birds. And now, as is characteristic of China’s new wave of philanthropists, he is expanding into activities abroad, in Canada, France, Nepal, Africa, and even the U.S.

“But there is a question that kept me up all last night,” Niu continues. “What is the most important thing rich people should do when they get together? Let’s think for a moment about what the earth will look like 500 years from now. The changes are unimaginable. We may have trains that travel 2,000 miles an hour. But one thing is certain: We will still have only five ecosystems. There will never be any others. We must protect them. Or are we humans simply going to be parasites on this planet?”

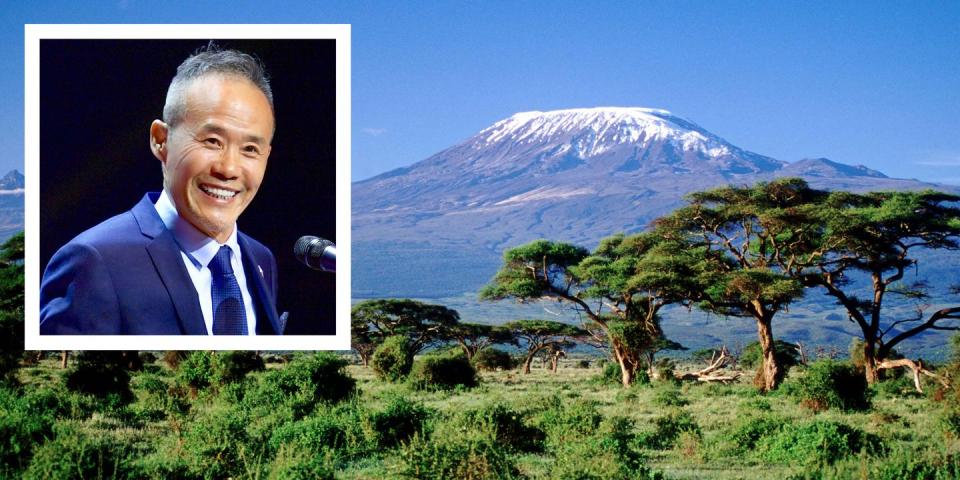

One of his compatriots, Wang Shi, founder (now chairman emeritus) of China Vanke, China’s largest and greenest real estate development firm, has an especially keen interest in fostering environmental integrity. “Half of all sustainable buildings in China are built by my company,” he asserts when it’s his time to take the stage. He too has a philanthropy, the Vanke Foundation, which he started in 2008 and which has donated millions to education, health, disaster relief, community development, and environmental protection. Wang’s personal nature lover credentials are significant. Trim, fit, and somehow glowing at 66, he is one of the relatively few people in the world who have summited the seven highest peaks on the seven continents and trekked to the North and South poles (“7 + 2,” it’s called).

“I did not see any snows on Kilimanjaro,” he tells the assembled in fluent English, a rarity among the Chinese in this crowd. “Was what Hemingway wrote a myth? No. But snow on Kilimanjaro has become seasonal because of global warming. We have to face the future. Because our technology is consuming the earth.”

In addition to the need for philanthropic action, Wang has another message for the Westerners in the room. “Thousands of elephants are killed every year in Africa, so our government banned the trade in tusks. Sharks are under threat because of the Chinese appetite for shark fins. Next year we will ban shark killing. What I’m trying to say is, be confident in the Chinese government. And try to understand Chinese culture. Look at the man’s face: He might be saying no, but it means yes. And also the other way around.”

“Look at him,” jokes the master of ceremonies, Wang Zhenyao, one of the summit’s organizers, after Wang Shi finishes. “A tough guy, but so humbly learning English!”

In addition to the speeches and the presentation by the summit’s major players, there are panel discussions and “united action” announcements by Chinese and American participants. (One last-minute no-show is Dang Yanbao, who made his fortune from coal mining but is now investing aggressively in clean energy and has built the world’s largest solar panel field-25 square miles-in Ningxia province.) I notice also many high-level huddles on the side. At one table at breakfast are the representatives of the foundations of Ray Dalio (founder of Bridgewater), Hank Paulson (former U.S. secretary of the treasury), and Paul Allen (Microsoft co-founder). It’s serious business, to do with oceans.

At a group luncheon on the summit’s second day I meet Dong Fangjun. Sporting a Hawaiian shirt and a lei, the 45-year-old Dong is introduced to me as the rising star in China’s ultrarich galaxy, founder of the Beijing Dong Fangjun Charitable Foundation and the second person in mainland China (after Niu Gensheng) to sign the Bill Gates/Warren Buffett Giving Pledge. His supersize undertaking is rehabilitating China’s countryside, much of which has been severely degraded (the price of the “Chinese miracle,” the headlong development that over the last three decades has lifted 700 million people out of poverty)

Modeling his initiative on Japanese billionaire Soichiro Fukutake’s groundbreaking rehabilitation of Naoshima Island (once an industrial wasteland, it is now a little slice of heaven, with a popular arts and cultural center and strong local employment), Dong has a pilot project underway called Peach Blossom Island. He likens it to one of George H.W. Bush’s “thousand points of light” (references to Western philanthropic style and gestures are frequent in this group), and he is actively scouting 10 other locations. Fukutake, who is in attendance, is helping underwrite the project, an instance of East-East collaboration.

“We are very confident,” Dong says, bursting with excitement, “that we will be able to improve our countryside and the lives of its 800 million farmers. Revitalize China, revitalize the world!”

In addition to the big players is a large contingent of “baby philanthropists” affiliated with the Shenzhen-based China Global Philanthropy Institute (CGPI). It was founded in 2014, after the first East-West Philanthropists Summit, by Bill Gates, Ray Dalio, and three Chinese billionaires, Niu Gensheng, He Qiaonyu, and Ye Qingjun, each of whom agreed to put in $2 million a year for five years (a $50 million total commitment).

While the East-West summit is about bringing the big players together, CGPI, a sort of school of philanthropy, aims to show budding Chinese philanthropists the ropes of global giving: setting goals, establishing metrics for success, and finding partnerships. To put it crassly, CGPI primes the pump. To put it more elegantly, as IUCN’s McGuffie did, “It’s about ensuring that global wealth is distributed evenly, not just for the sake of China but for the sake of the world.”

But are the motives in Chinese philanthropy as humanitarian as they seem? Of course the universal human impulse to help is in play. (Indeed, the event that spurred the founding of private philanthropies in China was the devastating 2008 earthquake in Sichuan, in which more than 87,000 died and 4.8 million were left homeless.)

All the same, philanthropy, from a geopolitical perspective, is also power. “Harshly put, largesse reduces its recipients to beggars,” says Orville Schell, director of the Center on U.S.-China Relations at the Asia Society in New York. “This tectonic shift in the world of philanthropy signals China’s moment of arrival. Remember that it was once called ‘the sick man of Asia.’ There is a deep and complex psychology behind China’s rise, and philanthropy is just its newest form.” (How the current standoff on trade and tariffs will affect Chinese giving is, at this point, anyone’s guess.)

During a break, I speak through a translator to Lu Dezhi, the scholarly, soft-spoken chairman of the Huamin Charity Foundation. In 2012 he established the Huamin Research Center at Rutgers University to help guide and encourage private Chinese giving, and he is a loquacious philosopher-prince of the nascent movement. “We are similar to and different from you,” he says. “Like the Carnegies, the Mellons, the Rockefellers, we are first-generation wealth, and we are creating foundations and starting to invest in projects that move society forward in important ways. But we do not have the religious background you had in America. We do not have a responsibility to God to share our money. Our decisions are more rational.”

So why the intensity of the Chinese speakers? “That’s because these issues are fresh to us,” he replies. “We are learning. We are surprised.” From the stage we have had presentations from scientists from the University of Hawaii and Columbia about collapsing coral reefs, ocean bottoms being strip-mined, a 350 million–strong wave of climate refugees. “It’s a total emergency. We are reacting in unjaded ways.”

Copies of Lu’s book, Capital and Collective Sharing, are stacked for the taking at the ballroom door. Jay Henderson, an adviser to the summit, distills Lu’s message: “Capitalism is nothing. It’s a bucket of warm spit if you don’t have some kind of heart, if you’re not willing to give.”

As committed as all these gentlemen are, the center of attention among the Chinese contingent is 52-year-old businesswoman He Qiaonyu. Seemingly born with a green thumb, she graduated from Beijing Forestry University (“I studied gardening, design, and nature conservation,” she told me when we first met, “and I was inspired by them all”) and made her fortune with the Beijing Orient Landscape and Ecology Company, parlaying a business selling bonsai trees into a contract to landscape the 2008 Olympics, and becoming the leader in gardening supplies and soil restoration.

Philanthropically, she burst on the scene in 2015, using $500 million worth of stock to fund the Beijing Qiaonyu Foundation, which she created in 2012 and dedicated from the get-go to environmental restoration (she differs in this respect from her compatriots). And she is reaching for the stars. “Our mission,” she informs me, “is to be the most influential nature conservation foundation in the world.”

Maybe all eyes are on He because she is the only woman here from the financial stratosphere (seventh among women on Forbes’s 2017 China Rich List, and 79th overall). Maybe it’s her diminutive stature combined with her exuberance (she gesticulates dramatically onstage, her voice rising). Maybe it’s her vision, which she articulates simply but affectingly, of an Avatar-like world in which we bow before nature once again. “Nature,” she says during one of her four talks, going cosmic, “should be the future. We need to invent a new way of life. We need to wake up. We need to go back. That is the point I want to make today. The others-what I have done-are not so important.”

But probably what puts He most firmly in the spotlight is her history of giving. In Marrakech in November 2016, at the United Nations South-South Cooperation Conference, she pledged $15 million to support sustainability projects in developing countries. The UN’s Jorge Chediek is here in Hawaii for the signing ceremony enshrining her gift, part of the summit’s agenda; while she’s onstage, cameras popping, she throws in another $1 million. (Carol Fox, the organizer of the summit and its convener-in-chief, points out that “in the NGO world, funding is always the problem. What is going on in China now is a very hopeful sign.”)

In Monaco last October, at IUCN’s Patrons of Nature gathering hosted by Prince Albert, she made that $1.5 billion pledge-the single largest personal commitment to environmental conservation ever. (Even sums significantly smaller than that are just not numbers one hears often in philanthropy-especially not in environmentally focused philanthropy, which affords neither naming rights nor other outward symbols of social prestige. As Justin Winters, executive director of DiCaprio’s foundation, says, “Less than 3 percent of global philanthropy currently goes to conservation. We are talking fractional dollars.”)

He’s gift is to be disbursed over seven years (through 2024) and will fund (take a deep breath): restoring biodiversity to 300 cities in China, cleaning up 200 rivers, managing 80 protected areas, rehabilitating 15 endangered species of fauna and flora, and hiring 6,000 people to do all that. Plus projects abroad.

Also in Monaco she pledged $20 million (over 10 years) for the protection of big cats and their habitats worldwide. This she did in partnership with the Global Alliance for Wild Cats (GAWC) and the Panthera organization. Phase one will focus on China’s snow leopards and Africa’s lions. “I want to be the queen of cats!” she exclaimed.

Her chemistry with the king of cats, Thomas Kaplan, is notable. (Kaplan and his wife Daphne Recanati Kaplan are the founders of Panthera as well as of GAWC, whose other members include Mohammed bin Zayed, the crown prince of Abu Dhabi, and Indian hedge fund billionaire Narendra Kothari.) Kaplan is among He Qiaonyu’s first American high-net-worth partners and is currently her conservation whisperer.

I ask Kaplan what He’s largesse means to him. “I feel that I held down the fort for decades, and now the cavalry has arrived,” he replies. “In 12 to 18 months China could change the world of conservation. I don’t think I’m being delusional. From being environmental destroyers of the world”-as coveters of rhino horns, lion bones, shark fins, and elephant tusks; as miners of Africa; and as polluters of everything-“they will become its saviors. They are rapidly changing the narrative. This is China’s awakening. And, historically speaking, when you awaken China you change the world.”

It is late on the summit’s last evening-everything, thanks to the general enthusiasm, has gone overtime-when He bounds onstage from the front row, where she has been assiduously taking notes. She is dressed all in white, with shiny silver platform sandals. “I was inspired by President Obama’s speech,” she says, referring to his appearance at the 2016 East-West Center Sustainability Summit. “So I also threw myself into marine conservation studies.” Up goes a PowerPoint slide listing seven key threats to marine environments around the world. “Oceans are the cradle of life. My foundation will take action before governments do, before scientists really know what to do. We have to move forward even without a perfect action plan. We have no time left.” She is going big again.

“And so I am announcing the formation of a Global Marine Conservation Action Alliance, to be based here in Hawaii.” Her voice getting louder, her words faster, she starts calling on people and foundations to join the cause. “Mr. Niu-he and I agree on a lot of things, and I think we will on the importance of this. Tom Kaplan-he has already agreed! Gordon Moore-he is not here, but we have been talking to his representatives. Also with Leonardo DiCaprio’s and Hank Paulson’s. Ray Dalio! I know he shares my dream. I believe we have gotten a chairman of the new marine center without even asking him!” “This,” Kaplan says, “is what it means to be recruited into Madame He’s army. I told you: a force of nature.”

She ratchets it up. “And we have other allies. We want President Obama to be honorary president of our alliance.”

By the time we move to a celebratory dinner a mere half hour later, Dalio has accepted his recruitment from afar and Obama has sent a message, which is read out loud, commending He on her initiative, eliding the question of the proposed alliance, but not shutting the door, either. “As you all know,” says Peter Rundlet, Obama’s man in Hawaii, “climate change and sustainability are deeply important to the president. And this conference, frankly, has prompted us to accelerate some things.”

As champagne is poured and photos are taken, it is difficult to know what to make of all this. The director of one American foundation tells me, “I’m just here to see what is happening. Whatever it is, it is moving very fast.”

The enthusiasm is infectious, but a skeptic might ask: Does the money exist? It is said that many great fortunes in China are highly leveraged. If the money is real, will it materialize as promised? Foreign exchange restrictions recently put in place by the Chinese government have made it harder, according to Rupert Hoogewerf of the “Hurun China Rich List,” “for the rich-listers to move money overseas.”

It seems as if the authoritarian Chinese state wants its powerful philanthropic players to have a global footprint-but then again, maybe not. He Qiaonyu is disarmingly direct: “There are always people questioning if we can achieve this. What we have promised we will get done. I know my business. And there is something new: government support is finally starting.” She is referring, in part, to the newly passed Charity Law, which has lifted burdensome taxes on charitable donations, and more importantly to the fact that Beijing will be the host in 2020 of the UN’s Convention on Biological Diversity. “The government wants achievements. In two years we will show you another Chinese miracle.”

Which gives rise to another puzzlement: Are China’s philanthropists, rather than acting independently, merely doing their government’s bidding as it aggressively extends its influence throughout the world? “You have to always remember,” Orville Schell points out, “that all fortunes in China still exist at the sufferance of the Party and can be dangerous to possess. So their owners are strongly susceptible to suggestion. But conservation and climate change is an area where there is actual convergence, where there is a possibility of true collaboration and the healthy transmission of funding, knowledge, and expertise.”

With the future of this planet hanging in the balance, perhaps we should say, as the great pragmatist Deng Xiaoping did when he turned China into a capitalist nation in everything but name: “I don’t care if the cat is black or white so long as it catches mice.”

As this article goes to press, He Qiaonyu is in New York attending a Giving Pledge gathering with Gates and Dalio. Discussions are well underway about the details of the Global Marine Conservation Action Alliance-its primary participants and its funding structure. And this month He is traveling for the first time to Africa-along with Jack Ma, founder of Alibaba and one of Asia’s richest businessmen. “We must do something about the rhinos, about the gorillas,” says He, words bound to bring tears of relief to Africa’s beleaguered conservationists. “And after we do something, I want to bring children from China there, so that they can understand.” Chinese philanthropists 3.0.

This story appears in the June/July 2018 issue of Town & Country. Subscribe Today

You Might Also Like