A Closer Look at Queen Elizabeth’s Most Elusive Estate: The Duchy of Lancaster

Friday was Royal Finance Day in England when Buckingham Palace released its annual Sovereign Grant Report giving chapter and verse on how $105 million of public money was spent funding the British monarchy. The report accounts for everything from the price of food and drink at state banquets to the cost of the train trips and royal golf excursions.

Yet absent from the fanfare announcement were any details about the Queen’s private funds, which sometimes top up the public grant. In the topsy-turvy world of Windsor wealth the dividing line between public and private assets is often blurred—and most fogbound of all is the Queen’s so-called “private estate.”

The Duchy of Lancaster is as slippery as some of the salmon which dart up the river on one of its country grounds. Like a shape-shifting creature it can flip between being a private estate one moment and a public entity the next. At times, it acts like a family trust, at others, a commercial business. British MPs who have tried to scrutinize its financial affairs have been left scratching their heads by its foggy features, which provide AAA protection. It is archaic, arcane, and because it cannot be pinned down, often anonymous and therefore, some complain, it slips under the radar of rigorous Parliamentary scrutiny.

How Much It’s Really Worth

Established by Henry IV in 1399 to supply a private nest-egg in case the king were deposed, the Duchy today comprises 45,700 acres of rural land, mainly in the north of England, plus some prime office space on London’s Strand (including the land for the hotel Savoy London) whose rental revenue provides a private income for the Queen.

This year profits hit a record $30 million. The Queen uses the bulk of the money to pay her personal overheads—including the costly Balmoral estate and her horse racing venture at Sandringham—but some of the cash (maybe as much as several million dollars) is earmarked to bankroll half a dozen of her close family (Princess Anne, Prince Edward, the Duke of Kent, etc.) who are “working royals” but do not receive public funds.

The big question frequently posed about the Duchy is whether it is actually private or not. This matters because if it is fully private, then like any other personal property, it should escape scrutiny from Parliament. But if it is fully public, then as state property it should escape any taxes legislated by Parliament. Of course, the monarchy would benefit from the best of both worlds.

The Palace maintains that it is a “private estate” and points to the fact that it has been the personal property of the reigning monarch since the end of the 14th century and it is held separately from all other Crown possessions. But in the course of combing the archives for my new book on the Queen’s wealth, I discovered that the Duchy is much less private than many would have us believe and much more vital to the monarch’s finances than anyone realised.

The History of the Duchy

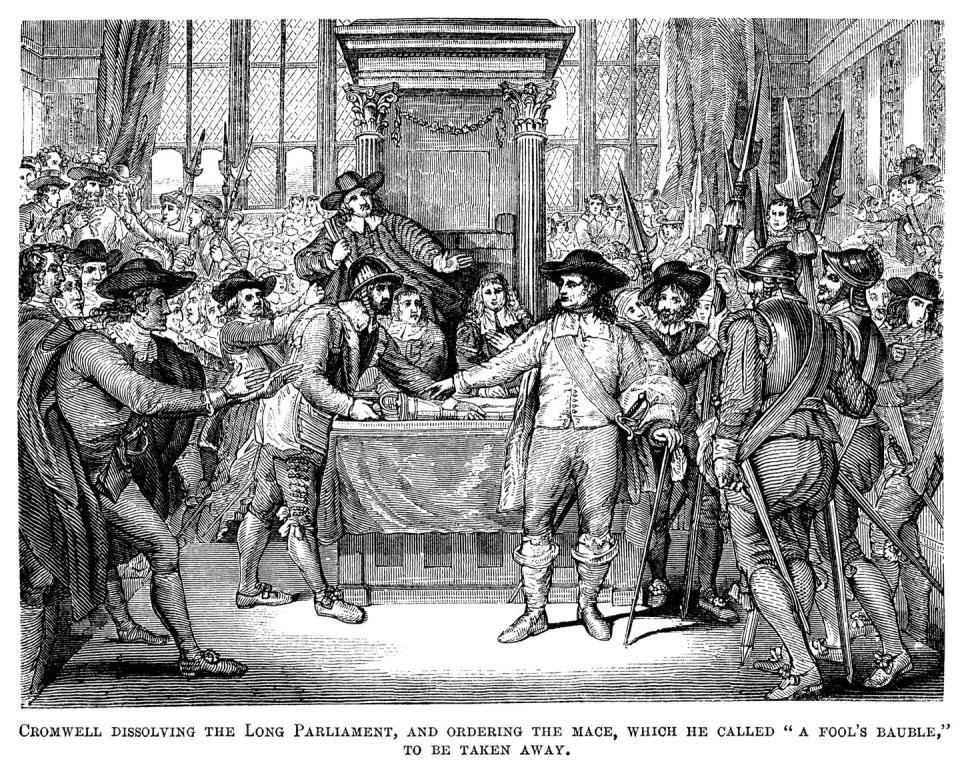

Over the centuries its original private status, established by two charters in 1399 and 1485, has been eroded by a battering of public assaults. The most significant came after the execution of Charles I in 1649 when, if the Duchy had actually been private, it should have passed automatically to his son Charles II. Instead, it was repossessed by the republican regime of Oliver Cromwell, with large swathes of land being sold off to pay for Civil War debts.

Later, after the restoration of the monarchy and the restitution of most of the land, the Duchy’s status took another grievous blow in 1688 when the deposed James II was not allowed to keep his supposedly private property. As I discovered in the privately-published official history of the estate, the key principle that “the Duchy followed the Crown”—i.e., monarchs only owned the property if they were actually on the throne—had now been “established” and would soon be set in stone.

Under George III, the estate achieved a rare success in 1760 when it was inexplicably excluded from the wholescale surrender of the hereditary Crown Estates to Parliament in return for a fixed Civil List public grant. The only possible reason for this was that its annual profits were so paltry at the time—a few hundred dollars—that it slipped through the net.

But when profits multiplied by a factor of twelve under Queen Victoria, Parliament made repeated attempts to have it transferred to the state, an assault only abated by a new law that gave MPs the power to scrutinize its annual accounts.

In 1936 Clement Attlee, a former Chancellor of the Duchy and future Prime Minister, went an important step further by tabling an amendment to a parliamentary bill to have the revenues of the Duchies of Lancaster and Cornwall surrendered to the public purse and arguing that they “cannot be considered in any way to be private estates.” Next, in 1972, the Labour MP Willy Hamilton actually brought in a private members’ bill to nationalise the two Duchies, and although it did not pass, as many as 104 MPs voted for it.

Between 1970 and 1972 the private status of the Duchy of Lancaster was significantly undermined when over $150,000 of its income was transferred to the public purse as an emergency measure to plug the shortfall in the Civil List caused by recent inflation. Indeed, a newly-discovered 1989 Treasury memo confirmed that such cross-funding was not uncommon: “some part of the revenues of the Duchy of Lancaster may have been absorbed in meeting official and semi-official expenditure.” According to Dame Margaret Hodge MP, the former Chair of Parliament’s financial watchdog committee, “to allege that it is a private estate is a little bit disingenuous.” To deny its public side smacks of “deliberate ambiguity.”

An Untouchable Estate

The vital importance of the Duchy to the Queen’s finances is shown by the way that whenever there is a major reform of royal funding—as happened on her accession in 1952 and most recently in 2012 with the replacement of the Civil List by the Sovereign Grant—her ancestral estate always escapes unscathed. As a newly-found Treasury memo tellingly put it, “one of the things the palace has insisted on is that there should be no surrender of the Duchy revenues.” In fact, the estate seems as well fortified as the security round Buckingham Palace.

Today the Duchy also benefits from two key tax breaks at variance to the way it does business. Although it operates like a land company, it pays neither corporation tax nor capital gains tax. The supposed reason for this immunity is that the Queen’s estate is akin to Crown property and the Crown cannot tax itself. But if it aspires to be Crown (i.e., state) property, then that makes it a public and not private estate—a classic example of how its status can be flipped to the most advantageous category.

With the aid of these tax privileges, along with some skillful management and a reconfiguration of the property portfolio into more lucrative urban land, Duchy profits have mushroomed during the Queen’s reign. According to a parliamentary briefing paper, profits are now $21 million higher in real terms than in 1952, when she took the throne. In fact, since the millennium, profits have almost quadrupled.

Thanks to this eye-watering flow of funds, the shape-shifting Duchy has morphed into the Queen’s cash cow—or to assign it yet another form, it is now the wellspring of her wealth.

Adapted by David McClure from his new book, The Queen’s True Worth (Lume Books; 2020).

You Might Also Like