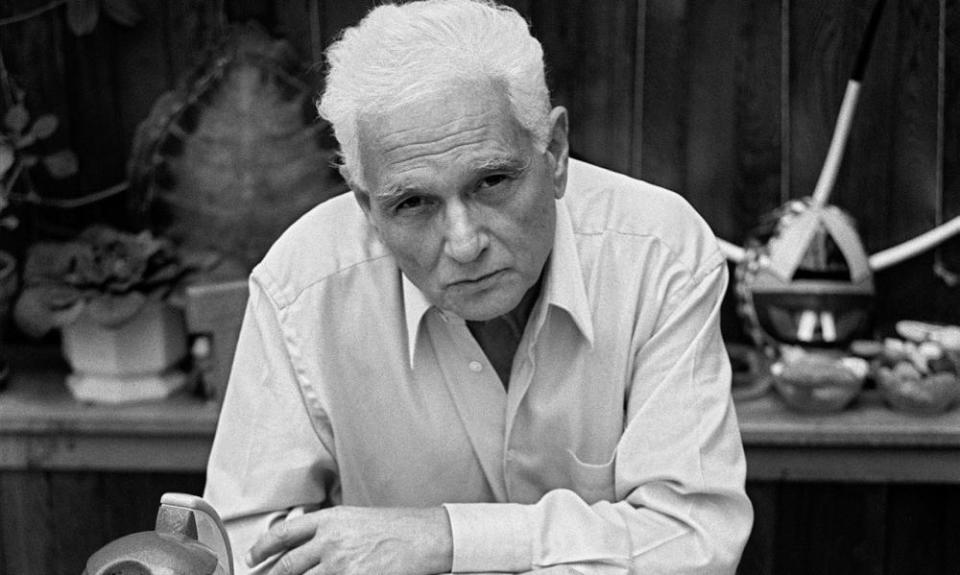

An Event, Perhaps by Peter Salmon review – a timely biography of Jacques Derrida

Jacques Derrida was born in Algiers in 1930 to a Jewish family of Spanish extraction. His parents named him after Jackie Coogan, the child star of Charlie Chaplin’s The Kid – a sign of the family’s sliding sense of origin and thoughts of life elsewhere. They aspired to the status of colonial French bourgeoisie, but were treated as Arab Jews, and were stripped of French citizenship during the second world war. As Peter Salmon tells us in his slim biography, Derrida later considered an equivocal identity essential to his intellectual development: “Could I explain anything without it, ever? No, nothing.” Add to this the death of an older brother, just 10 months before Jacques was born, and you have a writer convinced that the ground of thought and life might easily drop away.

Salmon is frustratingly reticent about the texture of his subject’s life, and frequently relies for both fact and surmise on the 2014 biography by Benoît Peeters; but he does give a vivid account of Derrida’s anxious entry into academic life. He was a serial mucker-up of exams, and when he eventually got into the prestigious École normale supérieure in Paris, he produced a thesis of which his mentor Louis Althusser said: “I can’t grade this, it’s too difficult, too obscure.” (Althusser passed it on to Michel Foucault, who declared it deserved either an A or an F.) Derrida was in his mid-30s before his dogged work on the phenomenology of Edmund Husserl turned into something else: a giddy pursuit, via close reading of the canon, of certain presuppositions in all of metaphysics. And a style to go with it, which his friend Jean Genet described best: “The usual coarse dynamism that leads a sentence to the next seems in Derrida to have been replaced by a very subtle magnetism, found not in words, but beneath them, almost under the page.”

It was as much his style as the concepts it supported (différance, logocentrism, hauntology) that seduced, or repelled, the Anglo-American academy and made of deconstruction – the name Derrida had given to his non-method – such a teeming and contentious field, especially in the 1970s and 80s. As early books such as Writing and Difference and Of Grammatology were translated into English, Derrida embarked on an extraordinarily energetic transatlantic career. He became a bigger star among literary academics abroad than he was among philosophers in France. His work turned more formally audacious: The Post Card (1980) was a delirious study of Socrates, Plato and Freud, and a barely concealed account of his long affair with the feminist philosopher Sylviane Agacinski.

In The Post Card, you get an endearing sense of Derrida’s scholarly excitement, his graphomania, his lifelong hypochondria: “I feel very sick, this time it’s the end, I feel it coming.” Also, what a friend called his “radiant narcissism”. In Salmon’s biography, much of this personality is absent or muted. Salmon seems not to have spoken to a soul who knew Derrida, refers not once to his archives in Paris or California, and keeps getting distracted by dutiful précis of the lives and works of the philosophers Derrida wrote about. The odd textual lapse aside, Salmon is an efficient summariser of Derrida’s thought. But even on a charitable reading – this is after all an intellectual biography, not an intimate life – his appraisals of character and reputation are rather banal: “Jacques Derrida continues to divide opinion. Genius or charlatan? Philosopher or fraud?”

Of course Derrida’s latest biographer is not alone in floating such cliches: the usual accusations of irrationality and obscurantism were aired at his death from pancreatic cancer in 2004, and perhaps will be again about Salmon’s book. Though Peeters’s highly readable, high-gossipy biography remains the standard, you could imagine a short, stylish critical life that countered all the stereotypes about “gnomic” French theory, essayed a real portrait of the man himself and acknowledged the sheer adventure of Derrida’s work. Such a book might situate the life of that work in Derrida’s unceasing feeling – when he thought about home, family or philosophy – of being haunted. “I think about nothing but death,” he wrote.

An Event, Perhaps is certainly timely. It appears in an era when, not for the first time, varieties of critical thought are being accused of a contradictory array of culture-war crimes and political upheavals. As Salmon reminds us, Derrida was among those the Norwegian mass murderer Anders Breivik blamed, in 2011, for “indoctrinating this new generation in feminist interpretation, Marxist philosophy and the so-called ‘queer theory’.” But deconstruction, sometimes blithely conflated with postmodernism (a subject that interested Derrida not at all), is also accused of having no beliefs or principles whatever at its core, other than the actual destruction of any idea of truth. The critic Michiko Kakutani, in her 2018 book The Death of Truth, went so far as to link the academic ascent of French theory – now somewhat antique a reference, surely, as well as arcane – to the rise of Donald Trump.

Derrida had been through all of this before, and parodied his opponents’ position thus: “So you ask yourself questions about truth. Well, to that extent, you do not as yet believe in truth.” It was not true. His writing is a model of the most careful reading – and a tireless lesson in how truth and lies are made.

• Brian Dillon’s Suppose a Sentence is published by Fitzcarraldo Editions. An Event, Perhaps: A Biography of Jacques Derrida is published by Verso (£16.99). To buy a copy go to guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.