Hear the people sing! Musicals are back – and they’re retuned for a new generation

Hamilton was the perfect peppy soundtrack to a gloomy mid-February weekend spent painting the hall, Evita injected drama into wet Tuesdays, Jesus Christ Superstar became a balm in anxious times, and walks around wintry Hackney marshes were spent with Willy Russell’s ill-fated Blood Brothers.

In a discombobulating, locked-down year when, if you were very lucky, days melded into one, musical soundtracks conjured harmonious, air-punching highs and fictional, finite lows. They felt cathartic and comforting.

I wasn’t alone. Friends would send me the trailer to the new West Side Story film or clips of He’s My Boy in Everybody’s Talking About Jamie. I would trade grainy 80s YouTubes of Marti Webb singing Tell Me On a Sunday or Barbara Dickson’s full-throated rendition of Tell Me It’s Not True. Musicals, says Nica Burns, co-owner of six West End theatres and producer of countless musicals including the recent hit Everybody’s Talking About Jamie, offered a chance to sing and dance around our kitchens. “You can’t do that with a play,” she says.

Stuttering out of lockdown, it’s unsurprising that musicals are set to reign supreme. Alongside the long-running classics in London’s West End, a musical of Amélie is enjoying a limited run; new productions of Les Misérables and Cabaret, the latter starring Eddie Redmayne and Jessie Buckley, are set to open in autumn; and Get Up, Stand Up, about the life of Bob Marley, is scheduled for October.

Andrew Lloyd Webber’s new Cinderella is due to open later this month – but probably only at half of the venue’s seating capacity.

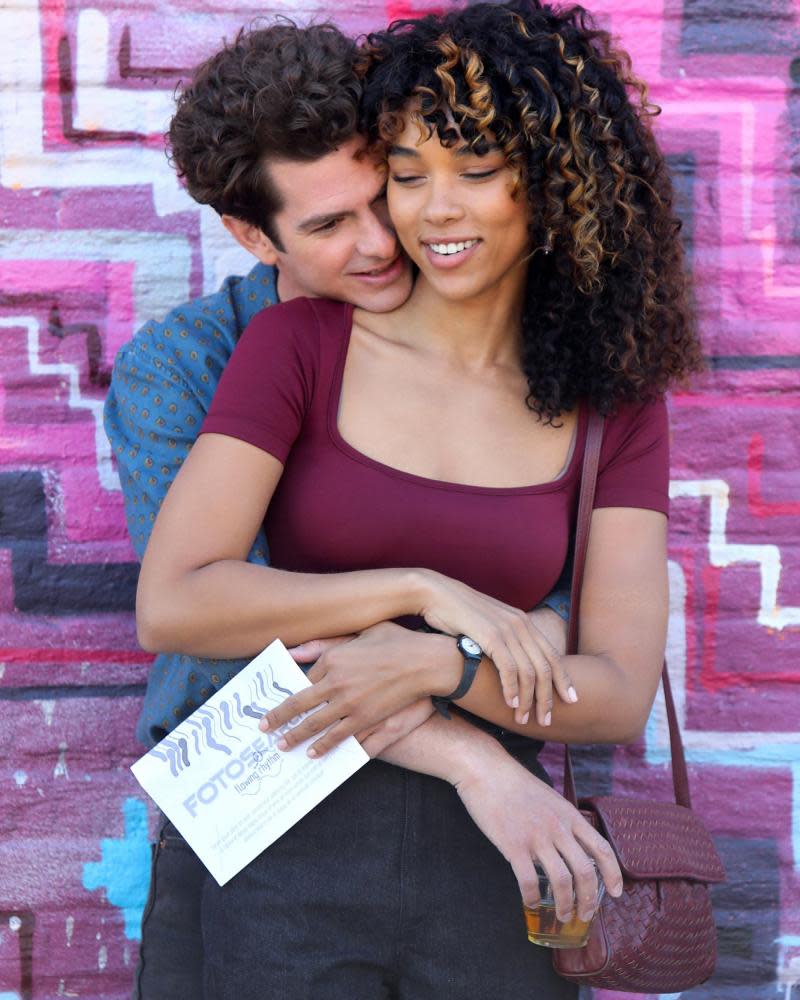

On the screen, Lin-Manuel Miranda’s In the Heights – adapted from his 2005 musical and directed by Crazy Rich Asians director Jon M Chu, who is also slated to direct a film of Wicked – has just been released in UK cinemas. Miranda’s directorial debut, Tick Tick … Boom!, is coming to Netflix in the autumn, and film adaptations of Everyone’s Talking about Jamie, Dear Evan Hansen and West Side Story, which will get the Spielberg treatment, are also due in the next few months.

Ryan McBryde, creative director at Colchester’s Mercury theatre, where a few years ago a new LGBTQ+ musical called Pieces of String won an award at the Stage Debut Awards, sees a post-lockdown appetite for musicals. “People want feelgood, euphoric escapism,” he says. What better way to get it than by watching a modern feminist take on the wives of Henry VIII? Shekinah McFarlane, who plays Anne of Cleves in the UK tour of Six: The Musical, agrees: “It’s that music, it’s the vibe, the chance to escape life for a bit and just live … you hear that rumble, and it’s like something that is so not like my life is about to go down.”

The reactions of audiences who have already made their way to socially distanced performances back this up. McFarlane recalls the reopening night in Canterbury: “The crowd were crazy, the energy was wild.” Even with many of the seats filled with cutouts rather than real people, the exuberance of those who were there made it feel “like we had a full audience even though half of them were cardboard … it was loud, it was raucous”.

This current musical moment dates further back than the pandemic, however. McBryde cites Rob Marshall’s 2002 version of Chicago as reinventing the genre. “That acted as a catalyst for showing the bankability of musicals,” he says. He also looks back to TV shows such as Glee and, later, Crazy Ex-Girlfriend. “It’s not something you go to the theatre to see, it’s something you can see every day – and they really tapped into a teen market.”

Burns cites Miranda’s global hit Hamilton as a catalyst. It won a Pulitzer and had punters reportedly forking out as much as $2,000 for tickets. “It pushed the boundaries in terms of how you can tell a story visually, in terms of the casting, how you present the material,” says Giles Terera, who played Aaron Burr in the original London production. It “challenged us all to re-evaluate how we tell stories.” According to McBryde, it brilliantly combined musical theatre tropes with “more accessible, much more popular styles of music, such as rap, R&B, jazz, which then appeal to a much wider audience”.

The diverse casting of Hamilton was also game-changing. Miranda’s In the Heights has similarly been celebrated in some quarters for breaking ground in representation, bringing a tale of a predominantly Latino neighbourhood in New York to the big screen with a predominantly Latino cast.

This year’s West Side Story remake is reportedly trying to redress some of the original’s wrongs, casting Latino actors where the 1961 version cast “browned up” white actors.

Rita Moreno, the Puerto Rican actress who was forced to darken her skin for her role as Anita in the original, has served as an executive producer. When she was recently asked what it felt like to now be in one of the driver’s seats, she commented: “At fucking last”.

But there is still a way to go – data from 2016 showed that diversity was still greatly lacking, both in casts and audiences, while In the Heights has been criticised for colourism because, as Miranda apologised, “many in our dark-skinned Afro-Latino community don’t feel sufficiently represented … particularly among the leading roles”.

From new stories to old ones told differently, and whether it started with Glee or Hamilton, or both, Burns believes we are living in a golden age of musicals. And, while she still treasures the classics, she celebrates the “new generation of musical-theatre creatives who have taken their place alongside the very best of the classical hits”. She points to the new Cinderella, which has seen Andrew Lloyd Webber team up with Emerald Fennell, writer of Promising Young Woman and Killing Eve, as a perfect embodiment of this. “You’ve got the most successful musical composer in the world teaming up with the hippest young female writer – that’s a rather exciting combination.”

There will, of course, always be those whose toes curl at mere mention of the word musical – the spontaneous bursting into song, the cheesy lines and earnest messages. But McBryde believes many of the new productions are shrugging off stereotypes by “tackling pretty significant topics – things like Dear Evan Hansen, which tackles depression; The Greatest Showman, which you could say is all about being an outsider”. Burns believes “everything that we are talking about for what we want for our societies are in these musicals”. Jamie, for instance, “is about the unconditional love of a mother for a son who’s different and is about tolerance, acceptance and celebrating difference.”

“In terms of relatability, new shows are really trying to listen to the voice of the audiences,” says McFarlane. “Younger people will be sat in that audience going ‘I can see myself here’, where it’s much harder to sit and go ‘yes, I relate to Jean Valjean from Les Mis’.”

Burns points to the way that The Wall in My Head, sung by Jamie, a teenager who wants to be a drag queen, about how a flippant comment from a parent can build to become a real barrier, has “really hit home in terms of the song that teenagers relate to”.

None of this is to say pre-2000 musicals don’t tap into real emotions – try to not get misty-eyed at Sunset Boulevard’s With One Look, or Fantine’s I Dreamed a Dream. Or that they didn’t speak to the realpolitik of their day. Film historian Pamela Hutchinson points to 1923’s Gold Diggers, which was about the Depression, as a good example.

Even old musicals relating to historical events can have a real-world potency now. It says something that Do You Hear the People Sing? from Les Misérables – a story about the Paris uprising of 1832, which premiered on Broadway in 1987 – became a protest anthem in Hong Kong in recent years.

Related: In the Heights review – Lin-Manuel Miranda musical loaded with Sunny-D optimism

Musicals as a genre, says Hutchinson, tap into this idea of solidarity most tangibly through the all-singing, all-dancing big production number. “You can look on-screen and see everyone’s going through the same thing, whether it’s the war or the depression or a pandemic”.

A city musical such as In the Heights will, she thinks, “hit a particular moment right now when we’ve all felt locked inside our homes; a musical about community is probably exactly what we want to see. It’s not escapism because it’s making us reflect on what we’ve lost in the last 18 months.”

“We all want to get back to being entertained en masse … we want to go to the cinema and see a large group of people reflected on the screen. I think that we could all do with a bit of fun right now.”