Inspired by Rimini: a tour of Fellini’s magical home town

Rimini is best-known for its vast swathe of Adriatic beach – and as the birthplace of revered film director Federico Fellini. The visionary behind La Dolce Vita and 8½ is regarded by fans and critics as one of the world’s greatest film-makers. I explored “his” city, including its Old Town, where Fellini grew up, taking in history and architecture that spans Roman to Renaissance, art nouveau to right-about-now in its compact, wanderable streets.

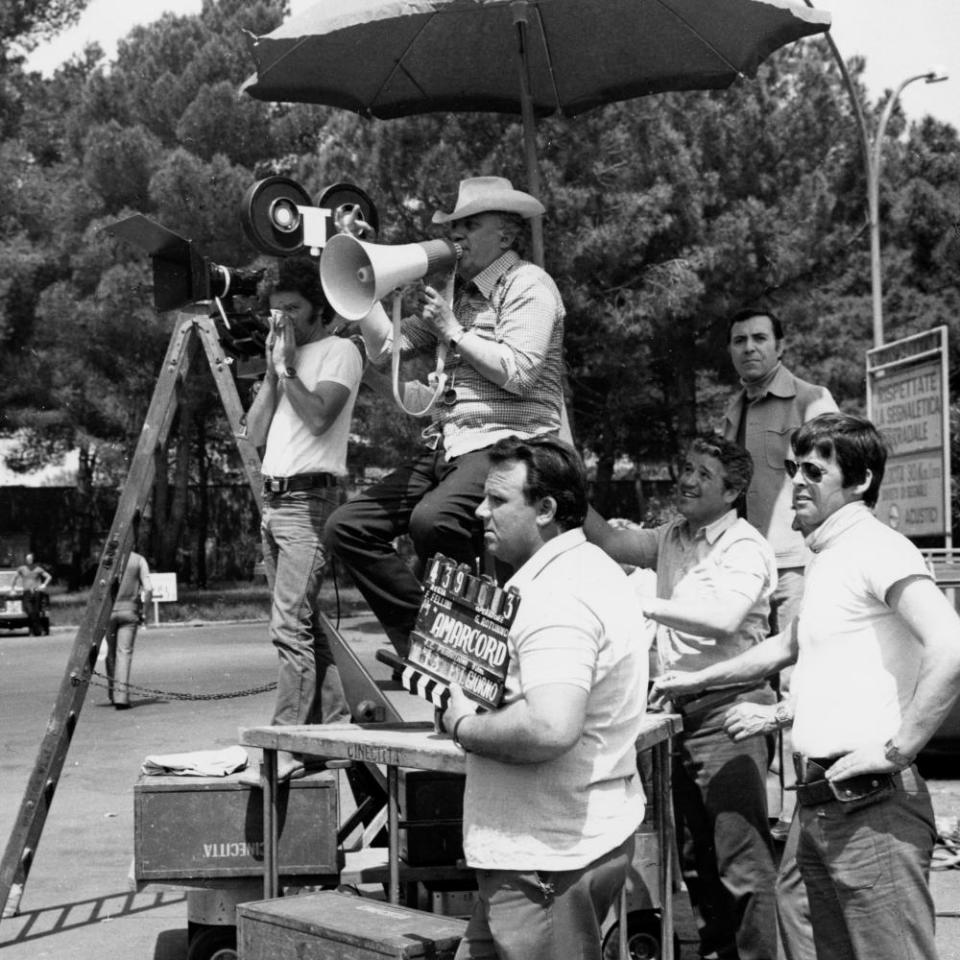

Fellini was born 100 years ago this month and spent his first 19 years in Rimini. The city, or his memories of it, has a starring role in several of his films – Amarcord (local dialect for “I Remember”) and I Vitelloni (The Layabouts) in particular, but appears in scenes in many others. He didn’t do any shooting here, but lovingly reconstructed his home town at the Cinecittà studios in Rome, and found surrogate stretches of beach just outside the capital. This year, Rimini will be celebrating its most famous son in a way that will leave a lasting legacy.

Aromas of sausage, truffle and coffee wafted through the winter air as I walked cobbled streets towards Piazza Cavour, the heart of Rimini since the middle ages. Along one side are the facades of the 17th-century town hall, the medieval Palazzo del Podestà and the 700-year-old Palazzo dell’Arengo – the latter two due to open on 14 March as a new contemporary art museum. In Amarcord, his 1973 Oscar-winner, Fellini has a strange parade for a fascist leader descend from the tower here. Amarcord is the film most closely associated with his view of Rimini, which he described in a 1960s essay entitled My Home Town, as “confused, frightening, tender, with that great breath of its own and its empty open sea”.

Dominating the end of the square, the neoclassical Teatro Amintore Galli sits on recently unearthed Roman remains. The theatre was opened by renowned composer Giuseppe Verdi in 1857 and reopened, after extensive restoration, just over a year ago – 75 years after it suffered major damage during a second world war air raid.

In Amarcord, Fellini turns the theatre into a church, introducing the other institution which, alongside fascism, shaped his 1930s upbringing. These terrors of his teens no longer hold such sway, but Rimini’s extraordinary Renaissance cathedral, the Tempio Malatestiano (with a disturbing Giotto crucifixion and a Piero della Francesca fresco) was still unsettling. I found its uncomfortable combination of empty and embellished, absorbing and belittling, very much as Fellini described it “inspiring … and slightly sinister”.

From Piazza Cavour, I wandered down the arcaded former fish market - its thick stone slabs now flower stalls and meeting spots – to a cluster of cafes and restaurants. Some were traditional, with older men deep into their newspapers; others were very much of the 21st century, such as La Hora Feliz, where a cocktail and an all-you-can-eat apericena buffet of mussels, beans, prosciutto, ricotta, meat, fish and pastas costs €11.

Fellini’s masterpieces frequently feature in lists of the top films of all time but his stature rests also on his impact. His episodic, carnivalesque style has been cited as an influence by directors including Martin Scorsese, George Lucas, Sofia Coppola and Pedro Almodóvar. And when Stanley Kubrick was asked for a list of his favourite films, he put I Vitelloni at number one.

Sadly, Fellini’s favourite bar is now an H&M but there are plenty of other places to sit and gaze at the world with a Fellinian eye. I watched as a monochrome man shuffled past, all in grey but for a multicoloured scarf like a beacon in a black-and-white print. A child danced across the square. I almost expected a perfect peacock to settle on the Renaissance fountain, as it does in Amarcord.

Visitors who time things right can see that scene on the big screen at the city’s art-nouveau Cinema Fulgor, which shows Amarcord at least once every three weeks. It’s the only Fellini film seen regularly in Rimini because it’s the one that’s affordable: its copyright is owned by the region. Cinema Fulgor turns 100 this year and has been recently refurbished to designs by Fellini’s friend and triple-Oscar-winning production designer Dante Ferretti. It has become a Fellini fantasy, with a red velvet-and-gold auditorium and a staircase of curves reminiscent of some of Fellini’s most memorable female characters.

There’s a new exhibition about the director – with photos, film clips, costumes, props and cartoons drawn by him – in the city’s Renaissance castle. A “dark presence” to young Fellini (it was then the city prison), Castel Sismondo hosts Fellini 100: Immortal Genius until 15 March, a sizable taster show in advance of the opening of the Federico Fellini International Museum in December 2020. This will occupy the castle, the upper floors of Cinema Fulgor and the outdoor space between them. Here, Amarcord will come full circle: A recreation of the Cinecittà reconstructed Rimini set will soon appear on the streets of its original model.

Wandering into the city’s other main square, Piazza Tre Martiri, I found the tiny green-domed Renaissance chapel of St Anthony. It was here that an adolescent Fellini and his friends watched country women pray before mounting their bicycles, and gazed at the “outlining, swelling … biggest and finest bums in the whole of Romagna” (a scene recreated in Amarcord). Rimini remains a city of cyclists.

The railway station is on the edge of the old town, and opposite is a new Bike Park, for cycle storage, but which will soon also rent bicycles. A 15-minute walk away, by the coast, Bike Tour Rimini is a good place to hire cycles. Bikes are included in the room rate at Soggiorni Diffusi, a B&B spread across three separate houses just across the Roman bridge in Borgo San Giuliano, the now-gentrified fishermen’s quarter. My favourite house was I Felliniani, complete with Fellini mural and three Fellini-themed rooms.

After a wander through the borgo, spotting more Fellini murals (including the kiss in the Trevi Fountain from 1960s La Dolce Vita), I went to Nud e Crud for a Rimini speciality, a piada. It’s a flatbread traditionally filled with prosciutto, squacquerone (local soft cheese) and rocket. Fortified, I set off on the 15-minute stroll to the coast.

Out of season the broad, sandy beach was empty, and very Fellini. “Vanishing into Rimini’s winter mists, lowered shutters, locked up boarding houses … the sound of the sea … from which come our monsters and ghosts,” he wrote. In summer, the beach is lost to sunbeds and sunseekers but his spirit remains year-round at the Grand Hotel, the still-splendid art-nouveau property on the waterfront. It was here that the young Fellini got his first glimpse of la dolce vita and here that – as a famous director, visiting from Rome – he always stayed.

I visited his favourite suite (guests can book it) with its red velvet furniture and view of the hotel gardens. This is where, in 1993, Fellini suffered the stroke that led to his death in Rome, a few months later.

His body is buried in Rimini’s cemetery, and I arrived at the grave, a dramatic abstraction of the prow of a ship, as darkness was falling. As I stood there, a cat, a sleek white-and-tabby, strolled up, rubbed itself against the grave and leapt into the monument before reappearing to look down at me from the high prow of the ship. Pure Fellini.

• The trip was provided by Emilia-Romagna Tourism. Soggiorni Diffusi has doubles from €80 B&B; Grand Hotel has doubles from €129 B&B. Fellini 100 runs in Rimini until 15 March, then touring. Further information at riminiturismo.it. Rimini can be reached from London by taking Eurostar to Paris, Thello sleeper to Milan, then local train to Rimini

Looking for a holiday with a difference? Browse Guardian Holidays to see a range of fantastic trips