Jasmine Camacho-Quinn wins gold for Puerto Rico, sparking another identity debate

For just the second time in history, an Olympian representing Puerto Rico, a small Caribbean island territory of the United States, stood on a podium with the Puerto Rican flag raised above two others as “La Borinqueña” played.

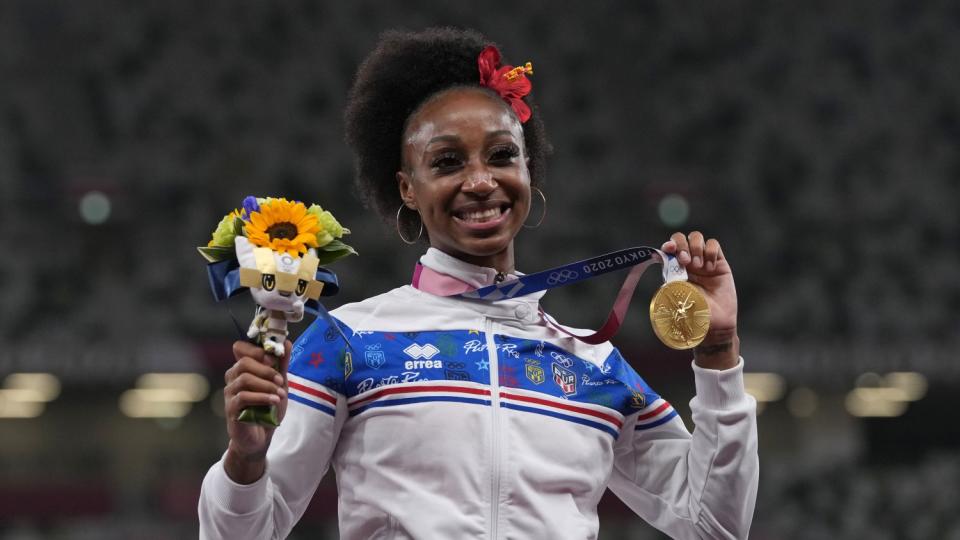

Jasmine Camacho-Quinn wiped away the tears flowing down her face and under her white mask during Puerto Rico’s national anthem on Monday at Olympic Stadium. She wore a large crimson flor de maga, the national flower, in her hair, above her left ear. Later, minus her mask, she broke into a glowing smile at officials in the stands waving a Puerto Rican flag.

Earlier in the day, she won gold in the women’s 100-meter hurdles. In Sunday’s semifinals, she set an Olympic record. She made it look easy.

“I’m pretty sure everybody’s excited,” Camacho-Quinn said after the race, still finding her breath. “Just to put on for such a small country, to give little kids hope. I’m just glad I’m the person to do that. I’m pretty happy with that.”

She then burst into tears.

The historic performance concluded a redemption tale — Camacho-Quinn failed to qualify for the final at the 2016 Olympics in Rio de Janeiro — and sparked celebrations across Puerto Rico, the diaspora, even in the air.

It also triggered naysayers who have maintained she isn’t Puerto Rican enough to represent the island, shedding light on the island’s complex national identity and its ambiguous position within the international sports landscape.

Camacho-Quinn, 24, comes from the expansive Puerto Rican diaspora; nearly 6 million people who live in the U.S. identify as Puerto Rican while the island’s population has dropped to 3.2 million.

She is the daughter of a Puerto Rican-born mother and a Black American father, born and raised in South Carolina not speaking Spanish. She starred at the University of Kentucky, winning three NCAA championships. She could have chosen to run for the United States but opted for Puerto Rico ahead of the 2016 Games as an homage to her mother.

Critics surfaced with her decision. She’s addressed them over the years, and offered a response from Japan in a tweet Saturday.

“You see my mommy? The PUERTO RICAN woman that birthed me?” Camacho-Quinn wrote above a video of her mother and other family members celebrating her preliminary first-place finish.

On Monday, before Camacho-Quinn’s gold-winning race, tennis player Gigi Fernández, the most accomplished Puerto Rican-born Olympic athlete in history, questioned Camacho-Quinn’s credentials in tweets that were later deleted. Camacho-Quinn is working to learn Spanish, an issue Fernández addressed.

“And is she Puerto Rican?” Fernández wrote in Spanish. “Does she speak Spanish? Was she raised in Puerto Rico? Hhmm. How curious.”

The comments elicited swift backlash, prompting Fernández to deactivate her Twitter account. It was not the first time Fernández tweeted controversial takes about Puerto Rican Olympians. In 2016, she questioned why wrestler Jaime Espinal, who was born in the Dominican Republic and won silver for Puerto Rico at the 2012 Olympics, was chosen as the nation’s flag bearer at the Rio Games.

On Monday, Sara Rosario, the president of the Puerto Rico Olympic Committee, dismissed the disapproval.

“I respect their opinions, but I think they're wrong,” Rosario said in Spanish. “Every four years when the Olympic Games arrive, they give these opinions. I don't see it as a necessary issue.”

Camacho-Quinn’s victory came five years after Monica Puig won women’s singles at the Rio Games for Puerto Rico’s long-awaited first Olympic gold medal. Until then, Puerto Rico had claimed two silvers and six bronzes since the island’s debut in 1948. Puig, however, wasn’t the first Puerto Rican-born person — or women’s tennis player — to win Olympic gold. That was Fernández.

Fernández earned gold medals at the 1992 and 1996 Games in women’s doubles for the United States, not Puerto Rico. She represented Puerto Rico in previous international events, but Puerto Rico couldn’t offer a doubles partner in the top 240 of the world rankings for the Olympics.

So Fernández, who rose to No. 1 in doubles in 1991, chose to compete in 1992 for the U.S. alongside Mary Joe Fernández, the No. 9-ranked doubles player in the world, to improve her odds of winning. The decision provoked scorn.

Fernández was given a choice because people born in Puerto Rico are U.S. citizens. Puerto Rico has been under the United States’ jurisdiction since the U.S. invaded the island and seized control from Spain in 1898 as part of the Spanish-American War but has maintained its own distinct culture and customs, with Spanish and English as the official languages.

The Jones Act of 1917 declared that any person born in Puerto Rico after April 24, 1898, was a U.S. citizen without the right to vote in presidential elections. Puerto Rico was given more autonomy — but remained under U.S. control — when Congress approved the Constitution of Puerto Rico in 1952.

Four years earlier, the International Olympic Committee, pursuing more participants, recognized the Puerto Rico Olympic Committee in time for the London Games. The U.S. did not intervene. Puerto Rico has sent its own delegation to every Summer Games since 1948, including the 1980 U.S.-boycotted Moscow Games.

“For us, it’s an honor to be here,” Pamela Rosado, the captain of Puerto Rican women’s basketball team, said in Spanish. “Having Puerto Rico on our chests, I think, is most important.”

Juan Venegas won Puerto Rico’s first medal — a bronze in boxing — at the 1948 Games. In 1984, boxer Luis Ortiz won Puerto Rico’s first silver. At the 2004 Games, Puerto Rico handed the United States men’s basketball team its first Olympic loss with NBA players.

Puig broke through for gold in 2016. On Monday, Camacho-Quinn followed. How many more times “La Borinqueña” is heard on the world’s biggest sporting stage could depend on the island’s political future.

Puerto Rico’s relationship with the United States dominates its politics. The island’s three prominent political parties are divided by the three leading status choices: the status quo, statehood and independence.

Statehood would likely end Puerto Rico’s sovereignty within the Olympics and Pan American Games under the Amateur Sports Act of 1978, which established that only one Olympic Committee can exist within the United States.

During his campaign last fall, Puerto Rican Gov. Pedro Pierluisi, the president of the pro-statehood New Progressive Party, said he’d hope that Puerto Rico could continue fielding its own delegations at other international competitions if the island was admitted into the union.

Both the IOC and United States Olympic and Paralympic Committee declined to comment on the matter.

“Everyone here is behind Puerto Rico,” said Esteban Pagán Rivera, the sports editor of El Nuevo Día, the biggest newspaper in Puerto Rico. “There aren’t many people paying attention to the United States.”

On Monday, Pierluisi tweeted congratulations to Camacho-Quinn. He thanked her for uniting the nation, giving Puerto Ricans happiness, filling them with pride and for representing Puerto Rican women in front of the world.

Staff writers Victoria Kim and Gary Klein contributed to this story.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.