Kehinde Wiley on His Pandemic Portraits, Mentorship, and Designing a New Platinum Card

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

The artist Kehinde Wiley, best-known for his portrait of President Barack Obama now at the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, was in Miami this week for a spell, and just that.

Unlike the marathon partiers on hand for the annual Art Basel Miami Beach fair and its constellation of satellite fairs, he would not be joining the rat race of dinners, openings, activations, or NFT launches. Instead, he would be wisely in and out in support of an organization that was instrumental to his artistic evolution, The Studio Museum, newly announced as the recipient of a $1 million gift by American Express backing the Harlem institution’s highly competitive Artist in Residence program.

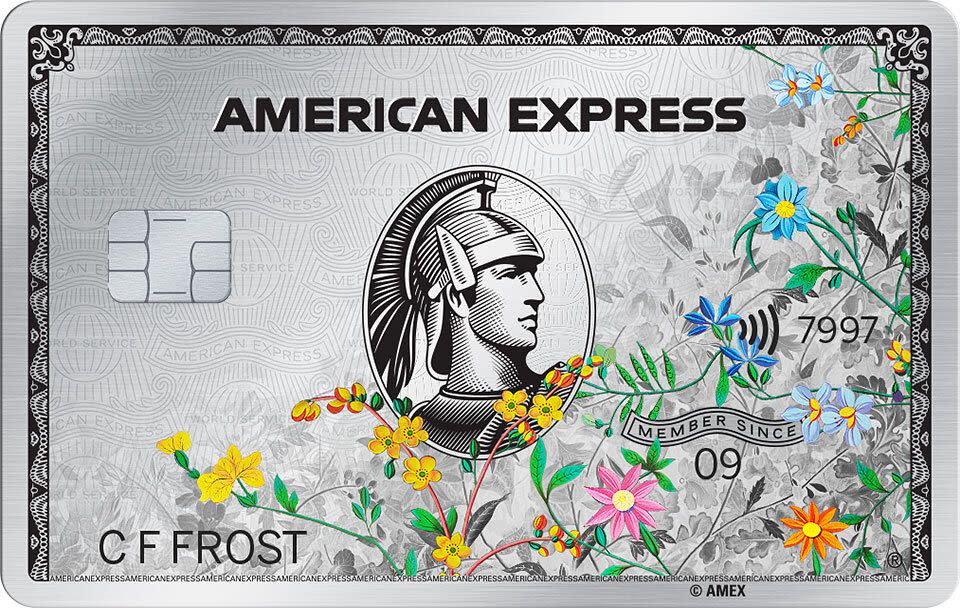

It’s a remarkable partnership that is expected to continue as the museum prepares for a major milestone, the opening in 2024 of its new home designed by David Adjaye. The museum’s patrons, and Amex card holders, can see the fruits of this collaboration much earlier, as Wiley and Julie Mehretu, alumni of the residency program, designed handsome, colorful new editions of the Platinum Card featuring some of their most recognizable motifs. (They will be available in January.)

“We wanted to think in more creative ways about the card design as a great experience,” said Rafael Mason, senior vice president, US Premium Products and Loyalty Programs. “And so, we collaborated with artists who are not only creative visionaries but also passionate believers in the power of giving back.”

Wiley developed his signature portraits exalting African American men in the style of European eighteenth- and nineteenth-century figurative paintings while in the museum’s residency program, but that wasn’t its only foundational lesson. He also drew from his experience there when in 2019 he began Black Rock Senegal, a highly selective residency program that invites emerging artists to live and work in Dakar for one to three months. When the pandemic hit, those stays were extended, and the seaside studio became something of a creative Eden not just for the up-and-comers, but for Wiley himself. The conversation below has been edited for clarity.

With Art Basel this week, Miami has felt like Kendall Roy's 40th birthday party. As an artist and art lover yourself, does it strike you that the art world has learned anything in the past two years, or is it just business as usual? That seems to be the case, if I'm just looking at sales figures.

Take your own life as an example. You're going to love being around friends. You're going to love looking forward to get with some celebration, but you're probably, if you're anything like me, going to have that moment where you finally got a gap year, where you can finally, I don't know, lick some old wounds and say, ‘Wow, this feels great,’ and I have new models for working and new ranges of possibilities in terms of what a creative life looks like. I think it's possible to walk and chew at the same time. To wild out and to recognize that this is a very big game-changer in society. This was a reset, and I don't think that, you know, a few days of partying in Miami is going to change that.

What have you been doing for the past two years? How did you reset your own compass?

Fortunately, a few years ago, I began building an Artist-in-Residence program in West Africa, and so, right as the world was shutting down, I had to make a very quick decision about where I wanted to be, and I made the fortuitous decision to go to Dakar, Senegal, which, as a country, had a sort of long track record of dealing with these large public health scares. And so they got very good at testing, they got very good at contact tracing and social distancing. All that stuff are things that we in the West hadn't learned, but they're like, oh, yeah, that. We dealt with, like, Ebola.

How is the residency program in Senegal going?

It’s up and running. Even during the pandemic, we were still running. We had artists who planned on being there for a month, and they were there for 8 or 9 months. And producing work the entire time, and we were all working side by side. The program runs year-round, so, we have artists who are there anywhere from 1 month to 3 months, depending on the realities of their lives. We try to make it pretty open to different walks of life so that if people have kids, they can bring them, and we cover everything from the transportation to the art materials to translators and drivers. It's a fully comprehensive experience. For the most part, they're emerging artists. They’re pretty formidable people. There’s thousands who apply, and there's only 18 to 20 spots every year. So, the odds are easier to get into Harvard or Yale.

Your experience at The Studio Museum’s Artist in Residence program must have informed your decision to launch a program like this of your own in West Africa.

Let’s face it. I was so heavily inspired by that place. I got my shot there. Even the dynamic of working with a very specific amount of artists—there's exactly three. That's what we're doing at Black Rock, and something about it means that it's large enough to have a bit of fluidity in terms of social movement, but even during the pandemic, we were all in lockdown together, including our staff. So, we got apartments. It was a creative pod. I literally started painting the people who work there. I did a whole series of paintings that are, like, you know, the pandemic paintings.

Lockdown portraits! How old were you when you got The Studio Museum's Artist-in-Residence? How transformative was it?

Let's see. I was just out of graduate school. I went straight into that from there, so 23 or 24. And yes, there had to be some kind of shaking off of the academic dynamic, the desire to somehow kind of measure up to the standard that the student body was bringing and for people modeling themselves after. It took a while to kind of pull away from that and really learn who I am or what I really, authentically like, rather than what I'm sort of being told is fashionable or appropriate. I think that happened in Harlem at The Studio Museum.

Were there moments that led to that artistic epiphany?

I knew that I was into portraiture specifically. I knew that I wanted to make something that was site-specific in response to New York, because, coming from California, I'd never really lived in New York. I went to graduate school in Connecticut. I wanted to make something that was almost like a postcard from Harlem kind of thing. What does it feel like to be here in a deeply pedestrian environment where you're always coming from a car culture in LA? Like, how do you get that sense of engaging the street life in what was then a very different type of African-American community, on, like, a Saturday? When everybody's out, and before social media, there was that sense of peacocking. It’s still, for me, very foundational and that trigger for engaging the streets. This is where I started street casting, by literally stopping people and saying, ‘Hi, I know this sounds kind of weird, but...’ It was inevitably magical.

It's literally a communion. Coming together. Making something new. In some respects, that’s also what happens in a residency program. I imagine that when this partnership with American Express came up to support the Studio Museum, you must have jumped at the chance to return the favor and, not to use a cliched word, but mentor younger artists, whether it’s through them, or your own program in Senegal.

No, but it's real. It's real. You start these things off thinking, ‘Okay, this might be kind of cool. Let's just give it a shot.’ And you realize that to throw yourself into something larger than yourself like this is what we all sort of seek in some way, in terms of creating meaning in our lives, but this has really enriched me in a way that's so authentic and so life-giving and recharged my intellectual batteries, my spiritual batteries.

That was also one of the epiphanies of the pandemic, right? To live your life, for lack of a better word, with a certain kind of purpose, and mentorship can be that.

It's true. It's true. It's kind of a perfect storm of things coming together. Like I said before, about five years before the pandemic was even here with us, the footwork and the foundation was laid for Black Rock to be built, and brick by brick, idea by idea, it all came together.

You mentioned that during the pandemic, you sort of discovered new forms of working, and to a certain extent, designing a credit card for Amex is the most democratic way that you could possibly reach people with art. Was that part of the appeal? Tell me about your thought process when they approached you.

I wanted it to feel like something's authentically coming from the vocabulary of a Kehinde Wiley painting. And so, what's so signature about what I do is I travel the world, searching different marketplaces, finding fabrics, finding models who are coming from specific cultural contexts, and allowing those things to come together in this kind of supernova, right? And so, no matter what walk of life you have, no matter where you come from, there can be some sort of relationship with this sort of decorative shard that comes from the paintings, and while you might not even know anything about Kehinde Wiley or the paintings, you're going to have your own sort of relationship with the way that card looks and feels in your life, in your world.

Decorative shard is the cutest way I've ever heard a credit card referred to.

I mean, on some level, there's something very aspirational about the history of art and the history of Western European easel painting, and there's a very easy confluence between the aspirational aspect of my work and the narrative surrounding allowing people of color now to occupy that space. So, I'm very aware of how it sits in the world, and I don't always say yes to a lot of these types of collaborations. I want to keep my integrity and make sure that it's something that feels real.

It’s important for The Studio Museum, too, and this is going to be longstanding relationship, as far as I understand it, in a sincere effort to support, really, one of New York’s leading arts organizations. Tell me about your card itself.

You're going to see is imagery that is directly pulled from specific paintings, and we’re putting bits and pieces together to create something that flows together in a way that feels good, that feels right, you know? It’s not quite like putting together a painting, because it's a much more sort of design problem, in a way, but it's coming from the painting.

Were there any technical challenges?

We live in an age now where the minute I shoot my models, I'm able to pull up the photos on the computer. I can start playing around with backgrounds, dropping out things, heightening and diminishing certain features. I think the hardest thing is just to arrive at what feels right in terms of it not being too noisy, not being, like, ‘What's that?’ You know, how do you want to live with an object in the world all the time?

Tell me about what's coming up for you in terms of your personal practice. I want to hear more about these lockdown portraits, and when can we get to see them?

Those are cool. I’m sort of in a holding pattern because I want to show them as a body of work. I think that'd be kind of interesting, but my exhibition schedule is pretty mapped out, so you're going to have to plan space to put it in. The next show opens in London on December 10. Taking over the National Gallery. It’ll be my first time launching a six-screen film. It’s an immersive experience shot in the fjords of Norway, creating this weird juxtaposition between Black skin and sheer white mountaintops in little blizzards and storms. It's heartbreakingly, gorgeous stuff, and then, of course, making paintings that are inspired by that as well.

You Might Also Like