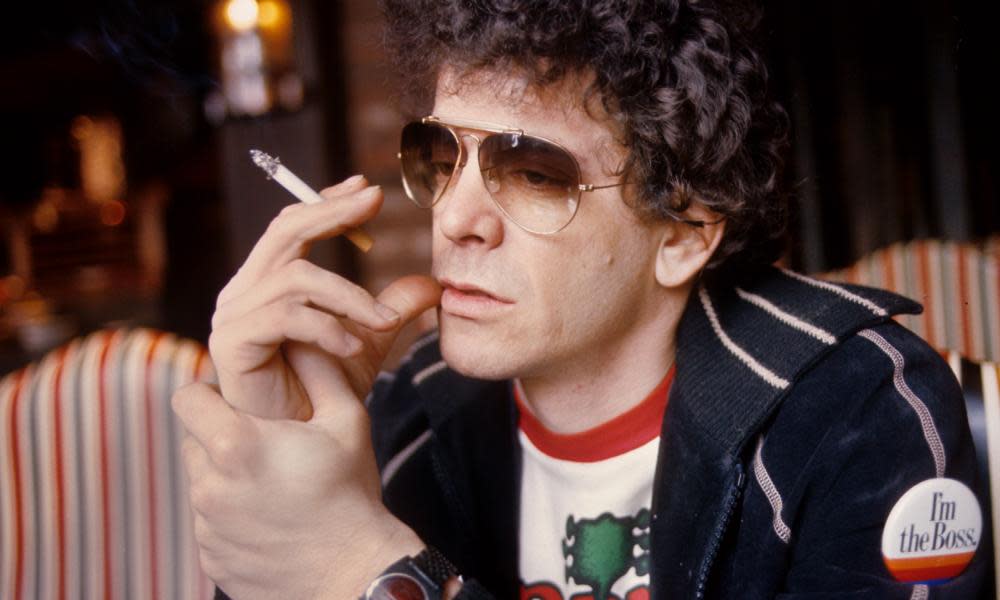

I’ll Be Your Mirror by Lou Reed review – bard of New York’s dirty boulevards

Lou Reed’s literary ambitions were there from the start, nurtured at Syracuse University in the early 1960s, where he studied English under the mysterious poet and short-story writer Delmore Schwartz, whom he would later acknowledge as his “spiritual godfather”. In 1966, having disappeared from public view for several years, Schwartz died alone and unsung, in a sleazy hotel in Times Square, aged 52. He had struggled with alcoholism, mental health issues and the heavy weight of early fame.

Schwartz could have been a character in a Lou Reed song. Instead, Reed wrote two songs about him. The first, European Son (to Delmore Schwartz), is the final track on the Velvet Underground’s 1967 debut album, The Velvet Underground & Nico. The song was actually recorded a few months before the poet’s death and sounds more like a put-down than a homage: “But now your blue clouds have gone/ You’d better say so long/ Hey hey, bye bye bye.” It may have been a riposte to the older writer’s oft-voiced disdain for the pop song.

In 1982, Reed opened his 11th solo album, The Blue Mask, with My House, an altogether more reflective song in which the singer describes his mentor as “the first great man that I had ever met”. He also compares their early friendship to that of Stephen Dedalus and Leopold Bloom in James Joyce’s Ulysses – no shrinking violet, Lou.

If Schwartz cast a long shadow, he was not the only ghost to haunt Reed’s lyrical imagination. In 1990, alongside his former Velvet Underground collaborator John Cale, he released Songs for Drella, an entire album of vignettes in memory of Andy Warhol, his other great creative touchstone. As I’ll Be Your Mirror, a revised version of Reed’s collected lyrics, highlights, he often trod a line between Warhol’s deadpan, almost nihilistic blankness and Schwartz’s more intensely descriptive and urgent poetry. Reed’s core musical influences were similarly wide-ranging, spanning the uncompromising free jazz of Ornette Coleman and the honeyed harmonies of countless 50s doo-wop groups.

Then there was his subject matter, which veered from the graphic (Heroin, I’m Waiting for the Man) to the intimate (Pale Blue Eyes, Perfect Day). Reed was nothing if not an artist of extremes. In one of the introductions to this volume, James Atlas describes him as “a nihilist who loved life”, which just about nails it. All this made him a singular songwriter, his best work often defined by that cruel-tender dynamic – has there ever been a more beautiful-sounding song about hustlers and speed freaks than Walk on the Wild Side? This hefty book is so full of contrasts that, were you coming cold to Reed’s oeuvre, it would be hard to reconcile the songwriter who penned the masochistic Venus in Furs with the romantic balladeer who, on I Found a Reason, croons: “I found a reason to keep living, and the reason dear is you.” Sinatra would have worked wonders with that couplet, but would not have ventured within a country mile of the former song’s “whiplash girl-child in the dark”.

Martin Scorsese, in his richly anecdotal intro, writes that Reed “spoke and sang in the voice of the lowest of the low, the dregs, the ‘least among us’ – the people looking for the first thing that gives them the right to be”. This shores up the notion of Reed as the ultimate “dirty realist” songwriter. It is this Reed who occupies an exalted place in the canon of rock songwriters: the street poet whose junkies, dealers and misfits inhabit a now all-but-vanished New York.

What intrigues most, though, as Reed’s lyrics are laid bare, are the myriad other Lous: camp Lou (Vicious), bitchy Lou (Hangin’ Round), nostalgic Lou (Coney Island Baby), hard-bitten Lou (Dirt), crassly provocative Lou (I Wanna Be Black) and, perhaps surprisingly, activist Lou (There Is No Time), whose call to arms seems even more urgent in today’s ongoing state of emergency.

Atlas makes the bold claim that I Wanna Be Black is “an astonishing poem” that would be “nearly impossible to imagine being recited anywhere by anyone today”. But astonishing is hardly the word for determinedly tasteless lines like: “I wanna be black/ Have natural rhythm/ Shoot twenty feet of jism, too/ And fuck up the Jews.” Deliberate offence in the service of satire no longer cuts it. Perhaps, as this song shows, it never really did.

Ultimately, I’ll Be Your Mirror suffers from the same disjuncture that afflicts all volumes of collected song lyrics: the distance between poetry and songwriting. Good poetry sings on the page; even the greatest songs struggle to find their voice in print. The deft and seductive Walk on the Wild Side falls flat here – “Doo da doo da doo/ Doo da doo” anyone? Likewise the sense of nihilistic enervation that Reed evokes in the repeated line “And I guess that I just don’t know”, on Heroin. What you are left with is an echo of the song that plays in your head as you read the words. Without the surge and sway of the music and Reed’s drawled delivery, the poetry is drained from the lines.

To borrow a line from Reed at his most determinedly Yeatsian, the lyrics alone struggle “to set the twilight reeling”.

• I’ll Be Your Mirror: The Collected Lyrics by Lou Reed is published by Faber (£25). To order a copy go to guardianbookshop.com or call 020-3176 3837. Free UK p&p over £15, online orders only. Phone orders min p&p of £1.99