How we made Viz: ‘We printed 150 copies for £42.52’

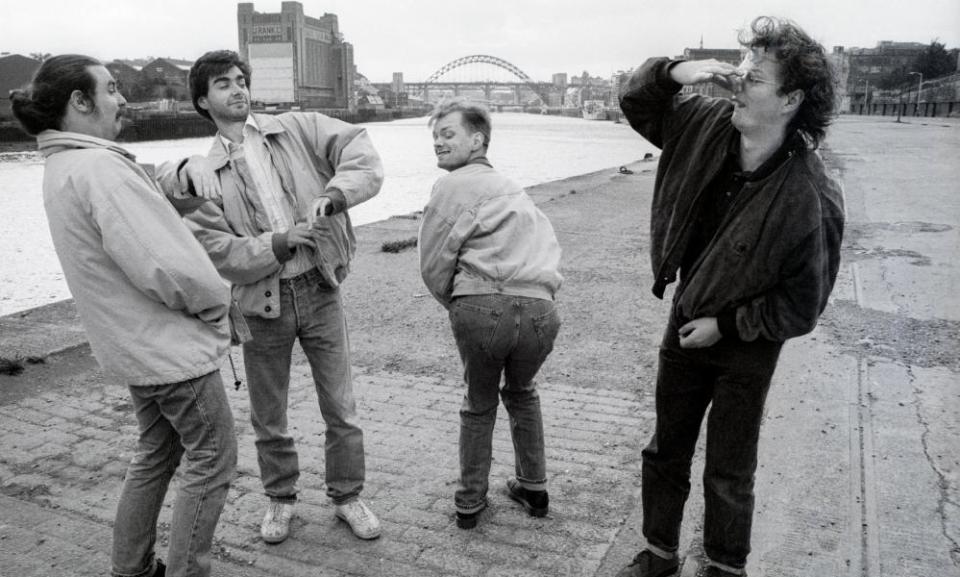

Simon Donald, co-creator

We grew up without a TV. Our house faced a railway line and my brother Chris made friends with a boy called Jim Brownlow through a shared love of trainspotting. One day, Jim brought this unspeakably foul record around: Derek and Clive. It was full of swearing. The idea that you could sell such vulgarity was stunning.

Jim also introduced us to adult comics like Fat Freddy’s Cat and The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers, which inspired Chris to start drawing little cartoons, such as an inept superhero called The Fat Crusader on our dad’s spare invoice pads, to pass around at school. Jim and Chris then created The Daily Pie, which was lots of little comic strips on one page of A4, and Arnold the Magazine, which we sold for 2p – the price of a photocopy – at pubs and youth clubs to amuse our friends.

Then they decided to do a proper comic and asked me to help. We chose the name Viz mainly because it was short and easy to draw. The first thing I said was: “Is it going to be on proper comic paper, like the Beano?” I came up with and drew Afternoon Tea With Mr Kiplin, where somebody goes around for tea at Mr Kiplin’s and is violently sick. It was pretty childish but I was only 15. Without realising it, we had touched on something: genuine schoolboy humour had never been put on paper before.

We launched in the winter of 1979 – the same week London Calling by the Clash came out. We printed 150 copies for £42.52 and they sold out – but at a loss. We sold them for 20p on the door of this punk gig in Newcastle. I was still at school and Chris was working at the Department of Health and Social Security, funding Viz on the side. The next issues ran to 500, 1,000, then 3,000. The next step was to start selling nationally. IPC Magazines were desperate to create a young men’s market, and were interested, but they insisted on watering down the content. Eventually, someone said: “Why don’t you try Richard Branson?” so we sent him a copy. John Brown, the head of Virgin Books, gave us a contract that let us retain editorial control. By 1985, Viz had gone national.

Chris Donald, co-creator

By the time we were selling nationwide, Viz had introduced a lot of its stalwarts: Johnny Fartpants, Billy the Fish and Biffa Bacon. Sid the Sexist was based on one of our friends, who simply didn’t know how to speak to women. When he did, he would say something horrendous. Roger Mellie came from when we’d been invited on to this youth show on Tyne Tees Television called Check It Out. We overheard Rod Griffith – the local news anchor – telling a dirty joke in the canteen. I was entranced by this familiar voice swearing. So I thought: “What would happen if a presenter swore on TV?”

The first issue published by Virgin sold 13,000 copies. John Brown took us with him to form his own company in 1987. By 1991, we were selling 1.2m copies, six times a year. I was in charge of the money so, one Christmas, I gave everyone a six-figure bonus. Simon had so many cars that he couldn’t move. I bought this old railway house and had to commute 50 miles back into Newcastle. We were still a cottage industry, so never got more than a few days off at a time. But when sales dropped, so did the bonuses and everyone got upset.

We never judged anything other than by whether it made us laugh. Unlike TV, we weren’t beamed into your home. You bought it by choice. One old dear wrote in to complain that she’d bought it for her grandson because it said “comic” – so we just removed the word comic. And another lady, who lived near the printing factory in Bristol, complained when some pages blew out of a skip into her garden. The Thieving Gypsy Bastards, however, was an error of judgment and we got hundreds of complaints.

The comic became so high profile that the sort of people who wouldn’t like it came into contact with it. So we did get some reaction to The Fat Slags and Millie Tant. We were a room full of schoolboys, but the designer and office manager were both girls. They’d shout at us, as responsible women would, but that just added to our naughtiness. We tried to come up with female characters, but our efforts were quite feeble. When people complained about The Fat Slags, that just enthused us to do more. There were complaints that they were stereotyping women as sex objects, but really they were using their sexuality to get what they wanted, so it was quite the opposite.

The first word we got into the dictionary was “hatstand” – from Roger Irrelevant (He’s Completely Hatstand), meaning mad. “Fnarr! Fnarr!” was never supposed to be pronounced “Fnarr! Fnarr!” It was more the nasal raspberry Kenneth Williams makes when he’s trying to suppress a snigger.

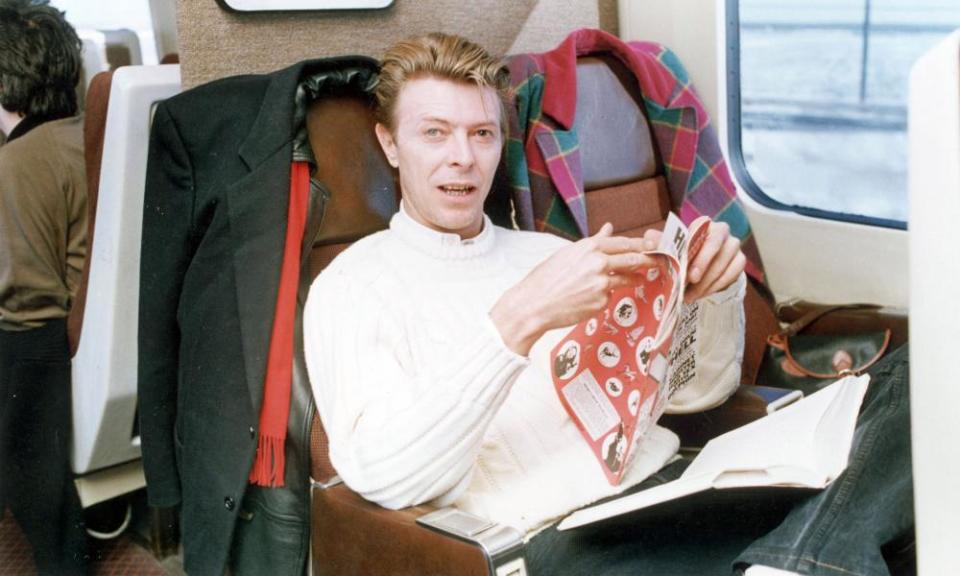

David Bowie was a big fan, maybe because our eldest brother, Steve, worked with him as an animatronics designer on the film Labyrinth. Journalist Auberon Waugh said: “If the future generations look back on the literature of the age, they’ll more usefully look to Viz than they would the novels of Peter Ackroyd or Julian Barnes.” His favourite strip was The Bottom Inspectors, by the way. It’s not bad considering my art teacher at school, who had seen my early comics, had told me to give it up and find a proper job.

• Him Off the Viz by Simon Donald is available from simondonald.com. Chris Donald’s Imaginary Soul Club is on Fridays, 10pm-1am on novaradio.co.uk. Simon and Chris’s gameshow, Donald Trumps, returns to Newcastle’s Stand Comedy Club later this year.