The Magician by Colm Tóibín review – inside the mind of Thomas Mann

In August 1939 Thomas Mann was in Sweden, staying in a seaside hotel. The mornings, as always, were devoted to his writing. After lunch with his family, he would take his afternoon walk on the beach.

Most of the hotel guests gathered in the lobby early to await the arrival of the foreign newspapers, but the Manns didn’t bother. They were not thinking much about international affairs. As Colm Tóibín describes it in this compelling fictionalised biography, it was a tranquil, drifting time. Then one morning Katia Mann broke the prohibition on disturbing her husband at work. She came to his room to tell him that war had broken out.

Days of suspense ensued. Telegrams. Anxiety. Last-minute rescue when places were found for them on a plane chartered by the Swedish authorities to evacuate foreign nationals. As they flew low through German airspace, Thomas – persona emphatically non grata in his native land since he had fled six years earlier – was trembling.

Tóibín has Mann reflecting that his literary tone identifies him as precisely what the newly ascendant Nazis most detest

In London there was a hitch. Mann was working on Lotte in Weimar, his novel about Goethe. Among his papers was a sketched plan of a dining room, with scribbled names around the table: just the sort of thing, thought the customs officer, a spy might be carrying. Mann tried to explain. This was an imaginary table plan, an aid to his fabrication of an imaginary conversation, which would, he hoped, tell the reader something real about another writer who had died a century earlier. Flummoxed by the apparent futility of the project, the customs man waved him through.

Like subject, like author. This is the second time Tóibín has used fiction to imagine his way into the mind of a past novelist. In 2004’s The Master he took his readers inside Henry James. Now he has chosen Mann. Both men wrote obliquely about homosexual desire without publicly acknowledging it in themselves. Both spent much of their lives away from their homelands. Both had elder brothers who were also distinguished authors (William James, Heinrich Mann) with whom they had complex, competitive relationships. Both were cosmopolitan, with social connections and intellectual interests that allowed them to see beyond the insular, class-bound worlds they described.

Another thing they had in common was a liking for strenuous ratiocination and very long sentences. This is where Tóibín’s interest in them becomes more surprising. Tóibín’s own prose can be Olympian in its cool simplicity, but simple it is. His limpid short stories and novels, such as Brooklyn, whose emotional power depends largely on the modesty of its style, could hardly be more different from James’s emotionally and linguistically elaborate creations, or from the troubled tone of Mann’s Dr Faustus or the labyrinthine musings of The Magic Mountain. But it is possible to admire great predecessors without precisely imitating them. In The Magician Tóibín has Mann reflecting, after winning his Nobel prize in 1929, that his literary tone – “ponderous, ceremonious, civilised” – identifies him as being precisely what the newly ascendant Nazis most detest. A mandarin style, a reserved manner, a dislike of political passion – these are quiet, unflashy attributes but, as Tóibín persuasively suggests, they are to be treasured as bulwarks against the sleep of reason and the monsters it spawns.

The Magician is first and foremost a portrait of the artist as a family man; there is comparatively little in it about Mann’s development as a writer or about his status in the literary world. Rather, it places him at the centre of a panoramic vision of the early 20th-century German cultural scene. Throughout his adult life Mann did his utmost to insulate himself against that scene – turbulent and threatening as it was – but, for all the rigour with which he forbade people to disturb him in his study, the outside world kept breaking in, most often given access by the antics and tribulations of his near relations.

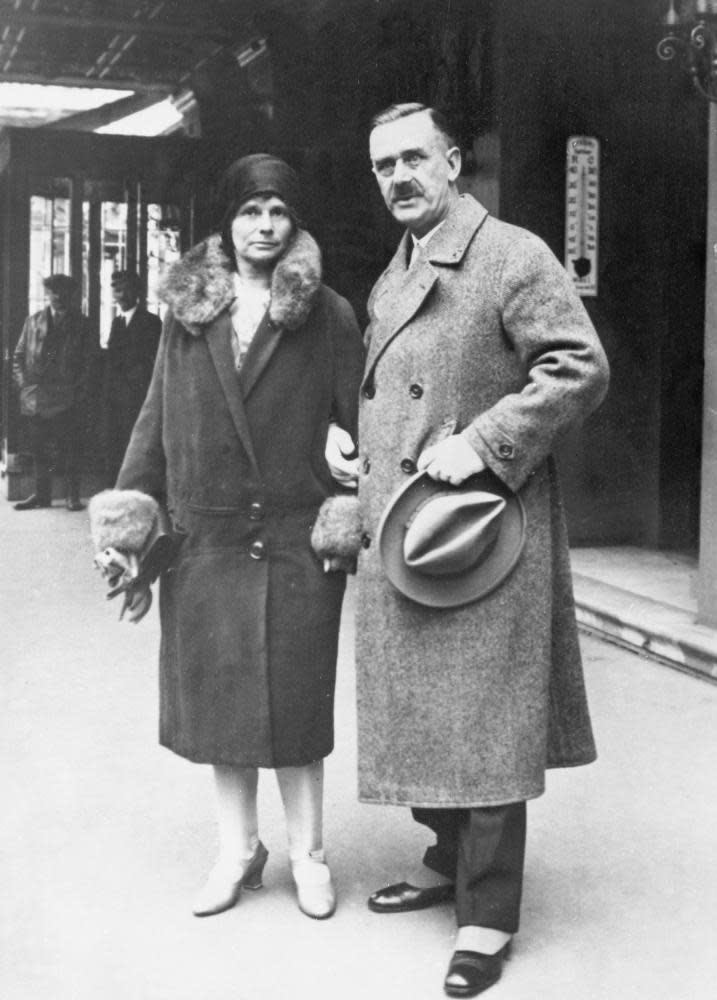

As anyone who has read Buddenbrooks could guess, Mann came from a line of successful Hanseatic merchants. His mother was Brazilian, an exotic figure in staid, bourgeois Lübeck. Widowed, she moved her family to Munich, where she and her children encountered a less convention-bound, more riskily exciting society. Thomas became fascinated by the Pringsheim family – rich, Bohemian, Wagner-worshipping, Jewish. He courted Katia, the daughter of the house, being primarily attracted, in Tóibín’s account, by her provocatively flirtatious relationship with her twin brother. He wrote a story in which the Pringsheim siblings merge with Wagner’s incestuous Siegfried and Sieglinde. Apparently unshocked, in 1905 Katia accepted his marriage proposal. Six children followed.

Buddenbrooks was his first novel, and it was a tremendous success. Soon he was celebrated and rich, but the family over which he presided was not as stolidly well-established as the grand house he built seemed to suggest. Both his sisters committed suicide. His two elder children, Erika and Klaus, were flamboyantly unconventional – promiscuously bisexual, precociously talented as actors and writers, but too politically reckless and financially feckless to make careers for themselves. There were drugs. There were scandals. Eventually there was another, more devastating suicide – Klaus’s – which Tóibín presents as a test of Mann’s humanity, a test he fails when he chooses to continue his lecture tour rather than attend his son’s funeral. And repeatedly there were young men at whom Tóibín’s Mann looks as yearningly, without ever touching them, as Mann’s Aschenbach gazes at Tadzio in Death in Venice. Katia sees it, and says nothing. His marriage is strong, but never quite enough.

Tóibín’s cast is large, and there are glittering vignettes. Erika Mann marries WH Auden, not for sex (they are both gay) but for a British passport; in a wonderfully comic scene Tóibín summons up Auden being acidically bitchy about Virginia Woolf. There is a memorably spiky account of Alma Mahler’s performance as grande dame in exile. But always behind the parade of characters lours the dark background of Germany’s decline and fall and subsequent division. Tóibín expertly balances the private and public, and he follows Mann’s trajectory from patriotism to disillusion with non-judgmental finesse.

In 1914 Tóibín has the rumours of war make themselves manifest as the rude rhymes Mann’s children are singing. “We hate Johnny Russia with his big smelly farts … We hate the English with their cold, cold hearts.” He imagines Mann, on the eve of war, alone in his opulently fixtured and fitted new house, reading German poetry and listening to German music, thinking how much he treasures Germany’s “deepening sense of its own soul, the intensity of its sombre self-interrogation”.

The first world war, though, dismays and confuses him. He writes a nationalist essay that he afterwards regrets. The 1918 Munich revolution makes him a target. He is saved from summary execution by Ernst Toller, the playwright turned revolutionary leader, whom he dislikes. When Hitler comes to power in 1933, Mann – with his Jewish wife, his socialist brother Heinrich and his outspokenly dissident children – is marked. He is no longer impressed by Teutonic high seriousness.

Related: Colm Tóibín: ‘I couldn’t read until I was nine – my first book was an Agatha Christie’

He escapes first to Switzerland, moving on to the south of France, where he frequents the cafes where other German exiles gather – social democrats bickering with communists – and finally to the US. He watches the second world war from transatlantic safety and has illuminating encounters with the powerful. Tóibín’s chilling account of his conversation with the financier and newspaper proprietor Eugene Meyer is masterly. Meyer’s formidable wife, the journalist and art collector Agnes Meyer, has brought Mann and some of his family to the US. Now he is required to pay for his freedom. Meyer passes on a message that emanates – though no names are mentioned – from President Roosevelt. Mann has been publicly calling upon America to intervene in Europe. Now he is told that America will enter the war, but in its own good time. “You want me to keep silent?” Mann asks. “They want you to become part of the strategy,” Meyer says. Mann wonders whether “Eugene dictated the Washington Post editorials in the same monotone as he used now”. Still impassive, Meyer tells Mann that if he cooperates, he could be the next German head of state. After their talk, Mann – appalled – resolves to move to California, well away from the centre of power.

When he pays a return visit to postwar Germany he is repelled by the machinations of west and east alike, each bloc attempting to make propagandist capital out of a visit that he had intended to be a celebration of concord. Politics have failed Mann and he turns his back on them. Tóibín grants him one last unconsummated infatuation with a compliant waiter, and then leaves him, an old man ready for death, thinking about a Germanic beauty that transcends ideological divisions, about Buxtehude and Bach.

This is an enormously ambitious book, one in which the intimate and the momentous are exquisitely balanced. It is the story of a man who spent almost all of his adult life behind a desk or going for sedate little post-prandial walks with his wife. From this sedentary existence Tóibín has fashioned an epic.

• Lucy Hughes-Hallett’s books include The Pike: Gabriele d’Annunzio, Poet, Seducer and Preacher of War (4th Estate). The Magician by Colm Tóibín is published by Viking (£18.99). To support the Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.