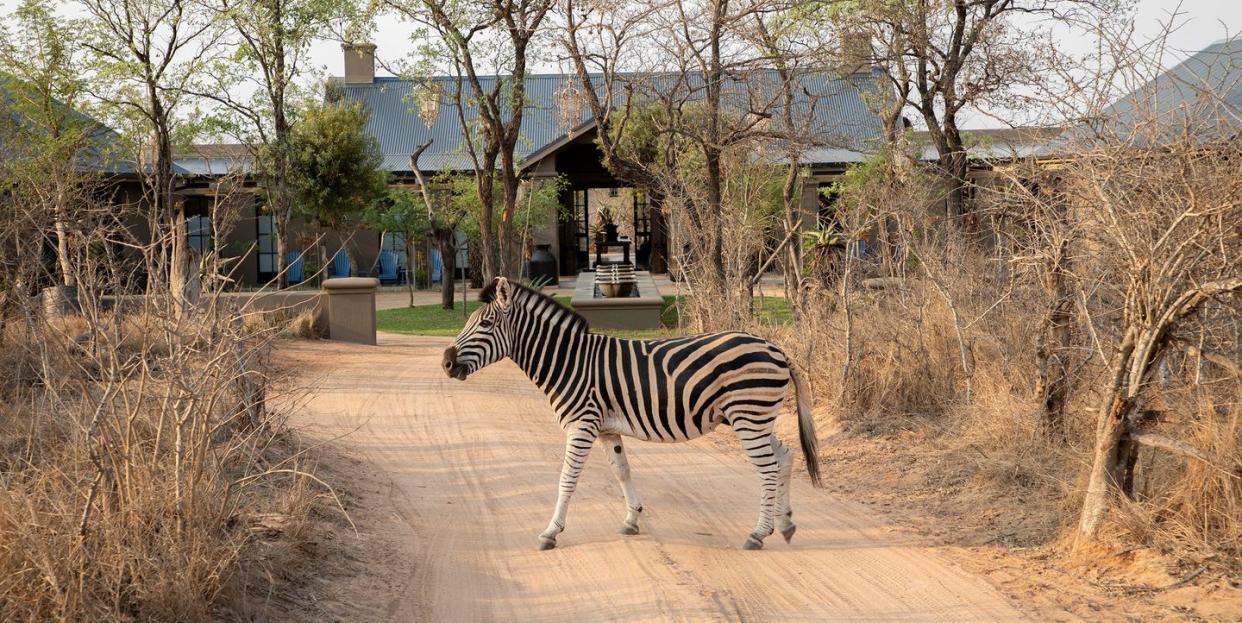

Melissa Biggs Bradley on Her New Book, Safari Style, and How We Should Travel Now

When I shut my eyes and have a dream of travel, it is more often than not about a safari camp somewhere in Africa–big nature, wild animals, sundowners and conversations around a fire, and that inimitable feeling of being completely in the present which all that inspires. Melissa Biggs Bradley, the founder and CEO of Indagare, the members-only, boutique travel-planning company, puts it this way in the first line of her new, richly photographic book, Safari Style: Exceptional African Camps and Lodges: "Africa gets in your blood." It sure does. Witness the first line of Isak Dinesen's Out of Africa: "I had a farm in Africa, at the foot of the Ngong Hills." Hers is allusive and full of longing, since Dinesen was already in Denmark when she wrote it, and was not going back to Kenya: You can almost hear the wistful sigh.

Bradley, a journalist by training and for more than a decade the travel editor of Town & Country, does go back to the African continent. A lot. She went as a child and she went on her honeymoon. She now goes for pleasure, with family; she goes to scout; and she leads trips there (in addition, of course, to organizing for Indagare members trips all over the world). She even went four times during the pandemic—and two of those trips were to lead small groups—10 and 12 people—to Rwanda. "They approached me," she says. It was before the vaccines, but "Rwanda was the first country to require negative Covid tests before you entered, again upon arrival, and again before you could see the gorillas. They were very buttoned up.")

So one afternoon a few weeks ago Bradley visited me in the Hearst tower in New York. There was jungle outside—concrete, not green, but magnificent in its own way—and the topic was Africa. (It was grand, although sundowners would have been nice.)

You began writing Safari Style before the pandemic and it was published right before the Omicron variant surfaced. Should we be thinking about trips to Africa now?

I've learned over the last two years that none of us can predict anything. But safaris occupy a special niche. When you're on safari, you're in a bubble. You're outside all the time. You're eating outside, walking outside, your game-drive vehicle is roofless. By definition, you're away from people. And those you are in contact with, like the staff at lodges, are in the same bubble you're in. No one is going into town to see their friends in the evening. Everyone is vaccinated and being tested, wearing masks, washing hands. Their livelihoods depend on maintaining the bubble. In Rwanda, you couldn't even be in a car with more than one person, unmasked, without getting fined. I felt safe.

You quote Hemingway in your book: "I never knew of a morning in Africa, when I woke up that I was not happy." When did you first realize the joy that being in the bush can bring?

My grandparents, who lived in New York City, traveled to Kenya in the 1960s and went back multiple times after that, for a month or two at a time. My grandmother was very reserved, very proper. But when she spoke about Kenya, about elephants, about giraffes, she became an entirely different person. I was intrigued about the place that could transform her in this way—from restrained to elated. She had stopped going after my grandfather's death, but once all her grandchildren were old enough, she said, "Okay, I'm taking everybody on safari, because this has just been so important to us, to me. So off we went. I was 12. There were probably 16 of us in the family and stayed an entire month. I ended up sharing a tent with her the entire time. And it was magical.

I can still remember every single day of that trip. Watching animals from terraces at night, the fires lit every evening, the walking safaris. Yes, we did that, too—we walked in the bush. We were kids, but we got with the program. We understood instinctually that the Masai who accompanied us knew what they were doing and that we had to listen carefully to them—or something bad could happen. I had been abroad before by then, because my mother is Australian. But I'd never been anywhere as culturally and environmentally different as Kenya. I fell completely in love with it, too. My second time on the continent was for my honeymoon, in South Africa, and since then, I've been on dozens of safaris, all over southern and eastern Africa. With friends and family, and also with clients.

You organize and lead many types of trips around the world. What's the special allure of the African safari?

For me, it just never gets old. I'm as excited to wake up in the bush after hundreds of such mornings as I was on the first. It comes from a number of things:

I'm a believer in what I heard a conservationist call the "deep species theory": That our attraction to these landscapes is genetic. Homo sapiens arose in this part of the world, and so, on a cellular level, there is this recognition, this flicker of...wait a minute, this feels familiar, this is where it all began, where we all began.

If you don't buy into that theory, there's something else, too. One meets people in the African bush who have not lost the language of the planet, of nature—a language the rest of us, in our harried modern lives, can't speak any more. When I come here, I feel like that little ancient memory of my earliest self is turned back on. I feel more connected to nature. I believe that all of us, whether we realize it or not, mourn the loss of that connection, that primal awareness. A client of mine said to me during a recent trip to Namibia: "It's so quiet here, you can almost hear your inner voice." Exactly.

And then there's the meditative aspect. I mediate. It's important to me to be in the here and now. And the African bush is to me like a physical manifestation of mediation. I am mostly unplugged from technology here; phones don't work. The bush pushes you into the present, forces you to be fully in the moment. If you're on a walking safari, or even in an open vehicle, you need to be constantly aware of your surroundings. You could die if you're not paying attention—to where you're putting you foot, to the sounds out there. I think that's one of the reasons I have such happy memories of being on safari with family and friends: because there's no looking around distractedly to see what else is going on. You are all just right there. Together.

A friend who took his kids on safari a number of years ago told me: "I've never spent that kind of time with my sons. It was a total level playing field. There was nothing that I had on them or they on me. There was nothing keeping us apart." In the eyes of a lion, we are all totally equal. That puts things wonderfully in perspective!

And then, of course, there's the beauty of it.

The safari is no longer your grandmother's safari. The premise of your book is that the top camps have evolved. How?

In eastern and southern Africa, lodges and camps have moved away from being largely hunting concessions to photographic ones. Furthermore, They now prioritize environmental conservation and community empowerment as much as they do the guest experience. They are leading the way in focusing attention on the importance of those issues—protecting wildlife and habitat, providing employment and job training to locals. And they're doing it more effectively, in some cases, than governments can. Much of that evolution is driven by visionaries. People like Dereck Joubert of Great Plains Conservation, Luke Bailes of Singita, Keith Vincent of Wilderness Safaris, Joss Kent of &Beyond. And others.

Was there an epicenter of this "new safari"?

Mombo Camp in Botswana was a model. Until the 1990s, Botswana—sparsely populated, unfenced, teeming with wildlife—was focused on trophy hunting. The Moremi Game Reserve, where Mombo was located, was a former hunting concession. But when Wilderness Safaris' founders Colin Bell and Chris McIntyre took over its management, they were able to prove that photographic safaris could be just as lucrative as hunting safaris. They spiffed up the rudimentary canvas tents, instituted better service, and demonstrated that a new breed of non-hunting safari goers would pay absolutely premium prices to experience remote wilderness in high style.

They proved, too, that they could provide more jobs and training to local communities than hunting operations did. It became a powerful model and resulted in the banning of hunting in all of Botswana. The ban was recently partially overturned by the new government, amid protest and controversy, but the country's concessions remain leased to high-end, conservation-minded safari companies who train and employ locals.

Another relatively new development was the advent of local guides in the camps—Africans who combine not just phenomenal formal training in biology, flora, and fauna, but also bring their ancestral knowledge to bear.

You feature 21 lodges in your book—in Kenya and Tanzania, South Africa and Namibia, Botswana and Zimbabwe, and Rwanda. How did you pick them?

I wanted each lodge to be an absolute "wow!" A place that would deliver on on everything someone could possibly dream of: amazing design, amazing guest experiences, amazing food, amazing game viewing. I also wanted them to be regionally representative, representative of the visionaries behind them, and to have a common denominator: a serious commitment to both conservation and community empowerment. But it's important that readers not look at this compendium as showing the only places they can go to. Rather, they are examples of the best out there—of what to look for, and which companies or operators to think about.

Similarly, there isn't a single "best safari." At Indagare, we act like matchmakers. If you're looking for the iconic, Out of Africa thing, you should probably go to East Africa—Kenya, Tanzania—and see the open plains. If you're looking for high-octane adventure, you should probably go to Zimbabwe and raft the Zambezi. If you want culture, go to Namibia, or Ethiopia, where you can actually be with tribes.

Do you have a favorite lodge, personally?

No, I don't. But I do love places where I can hear the night when I fall asleep, and things stirring when I wake up in the morning. As much as I can appreciate the role of the more palatial places—and they've certainly wowed me—I tend to always want to go back to the simpler, more natural ones. I don't need to get a blow-out, or eat Daniel Boulud food in the bush. But that's just me. For others, it makes all the difference.

What has been the effect, over the last two years, of the dramatic drop in tourism on the lodges and the communities dependent on them?

It's been devastating. This book started out celebrating the power of travel to have a true impact on conservation and community empowerment in Africa—look at these lodges, look how spectacular they are, and know that they are also doing good in addition to showing you a good time. Now? I hope that the book will also be seen as a call to action. We actually cannot wait for Covid to go away fully before we return to safari. We really do have to support African lodges—now. Many have closed, possibly permanently. Thankfully, not the lodges in this book, because they have deep pockets, and wealthy people behind them. But if we wait to return, educations will be lost, livelihoods will be lost, animals and ecosystems will suffer.

It's already happening. In Kenya last January, for instance, 25 percent of lodges in and around the Masai Mara were closed. Possibly permanently. A corresponding number of girls between the ages of 14 and 18 were no longer in school. And that's a direct result of people in their communities losing their income. Without that income, girls can't afford to go to school. Or they are being married off for their dowry, getting pregnant, and leaving the workforce for good. They're the new lost generation. Everyone in the lodges talks about it.

It's a similar situation in Rwanda. In the last two decades, that country has gone from true hell—the 1994 genocide was one of the worst things in our lifetime—to this beacon of hope in Africa, with high literacy rates, good health care, many women in Parliament. Just phenomenal. And a lot of that was driven by tourism.

And the mountain gorillas in Volcanoes National Park are one of the few endangered species whose numbers are truly rising. Again, the effect of funds generated by tourism. The country became crazy popular about 4 or 5 years ago. Because it was giving out only 96 gorilla trekking permits a day (so as to not stress the animals), it meant you had to book a year and a half in advance for your chance to see them. The rangers in Volcanoes would take people up to the gorillas 5 days a week, eight people per group. Now, because there are few travelers, they're doing 2 or 3 groups a month.

This is the rangers' and the porters' entire source of income. It was so stark to see. Rwanda has also seen more poaching recently—people are hungry. And that, of course, is magnified all over the continent. When I was in Kenya last January, our guide said that in the 15 years that he's been guiding, "I've never seen it this empty. And I don't think for the rest of our lives we'll see it like this." It's mission critical to go back there.

Thinking purely selfishly, are there advantages or opportunities for travelers willing to go now?

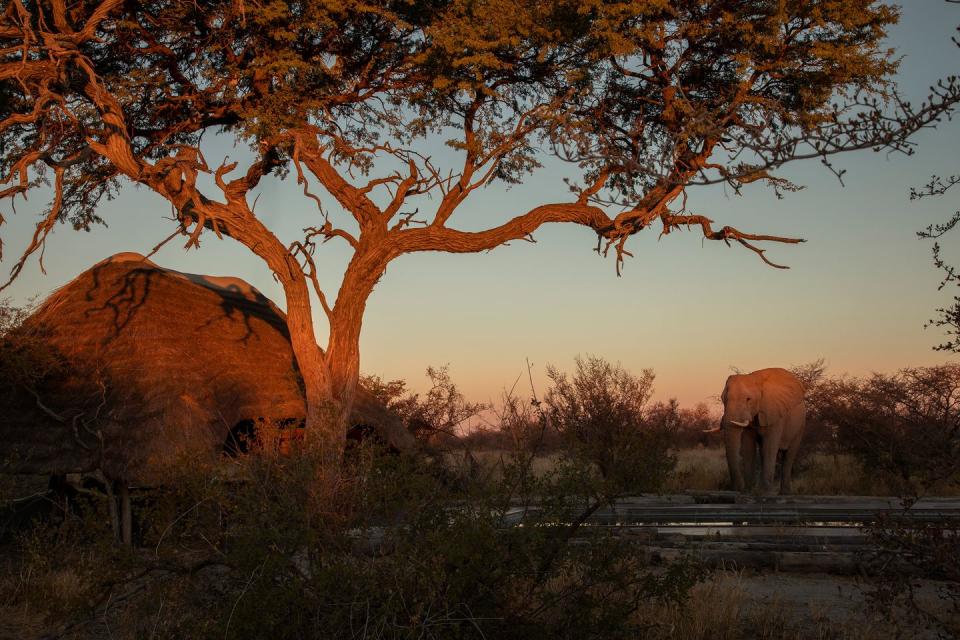

Yes. Wildlife behavior around the lodges has changed noticeably. Because there are so many fewer encounters with humans, animals become habituated to our presence more easily. There is less human pressure on them: less noise, fewer game-drive vehicles. etcetera. One of my guides was saying that the normal habituation to vehicles for lion cubs is around five months, with vehicles going out every day. During Covid, these little guys were coming over within a month. When I was in Rwanda in November 202o, a leopard brought her cubs literally under the floorboards at Magashi lodge, in Akagera National Park. Normally, that would never happen.

And there are also booking opportunities if you're flexible and patient. In pre-Covid times, you needed to book a safari at least 12 or 18 months in advance because space is always scarce at the small, premium lodges. But people, of course, have been postponing—from 2020 to 2021, from 2021 to 2022, and now some are postponing to late 2022 and early 2023. But each time that happens, they are creating an opening for someone else. If you can travel on fairly short notice, there might suddenly be space at a camp you were dreaming of. Keep checking—and be ready to go for it. And be sure to buy travel insurance. So much is out of our control, but with insurance, you have some peace of mind.

What do you say to people pondering the nearly Shakespearean question, "to go or not to go?"

Know thyself. I think of most of us in this era of Covid as falling into one of three categories:

There are the trailblazers, people who feel that time has been stolen from them by the pandemic. Their attitude is one of personal accountability: I can mask, I can wash my hands, and I can go someplace. Those are the people who went to Rwanda with me. They are flexible and grateful for the time they have.

There are the terrified: They are not traveling until Covid ends, and are fine with that.

And then—and this is the largest group—there are those who are on the fence and trying to find their way. They are not as eager as the first group, not as nervous as the second, but their travel muscles have atrophied.

To them I say: You have to assume a different mind set. Travel is not going to be like it used to be. If we want to travel, we will have to accept a new level of risk and uncertainty. I went to France for two weeks this past summer, and to Italy for two weeks. In Italy, there would be 24 of us on a boat. Statistically, even though we were all vaccinated, one of us should have a breakthrough infection. Which would mean having to quarantine in Italy. I decided that there are things I cannot live with, but getting stuck for two weeks in Italy is not one of them. I have my books, I have work I can do. That's what you have to think about: What if you have a positive Covid test on arrival or departure, and get stuck? Can you live with it?

Final word on travel generally?

Be patient. The travel industry has been battered and bruised and beaten. You can't show up and expect everything to be the same. Hotels have 40 percent of their staff, and half of them have been living on unemployment for almost two years. Airline staffs are 30 percent of what they were.

Final word on the African safari?

It's an incredible time to travel. There have never been fewer tourists, and there probably never will be again. It is also so important to support by your presence the conservation work these safari lodges are doing. Yes, you have to jump through hoops to get there, but wow, will you be rewarded.

You Might Also Like