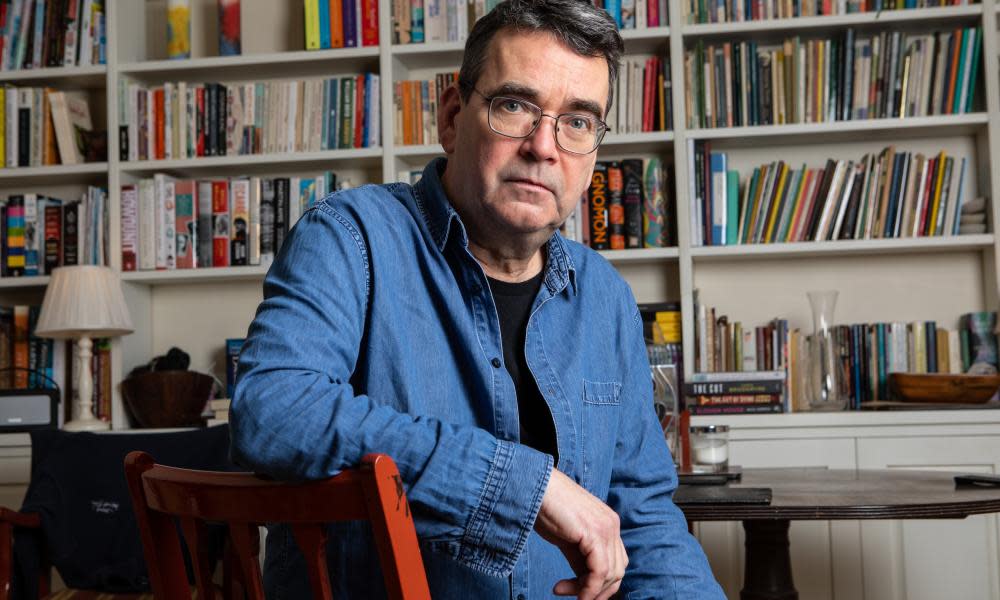

Mick Herron: 'I look at Jackson Lamb and think: My God, did I write that? My mother reads this stuff!'

Were it not for the packed bookshelves – everything from Len Deighton to the complete Philip Larkin – you could almost imagine the novelist Mick Herron’s flat as a safe house, plain and modest as it is, tucked away in a rather anonymous modern block in Oxford. The other immediate impression given by his home is of – how shall I put it? – antiquity. He’s still buying CDs (there’s a soaring Gavin Bryars choral work playing on the stereo) and at one point he produces his mobile, which, like the vast Toshiba laptop enthroned on a side table, seems suspiciously elderly. “It’s not a smartphone. I switch it on and it works. I don’t like having to learn new things, I’m too lazy,” he says. Before lockdown he had no wifi, either. “Obviously there are things I would need to check, and I would go out and do that.” At this point I look at him as if he’s just told me he gathers information by examining the entrails of birds. “In libraries,” he explains, gently.

He is clearly not lazy, not at all, about the stuff that matters to him. Herron is the author of the hugely entertaining Jackson Lamb series, about a stunningly inept collection of secret agents. These mess-ups and headcases have been banished from the sleek MI5 headquarters in Regent’s Park, London, to the secret service’s institutional oubliette Slough House, a grotty office block near the Barbican. Which is also the title of the seventh and latest novel in the series, published next month.

The books have become critical and commercial successes, and when I pay Herron a socially distant visit, filming is under way on Slow Horses, an adaptation for Apple TV. The Oscar-winning actor Gary Oldman is playing Lamb, Kristin Scott Thomas the steely apparatchik Diana Taverner, and Jack Lowden the disgraced young agent River Cartwright. For someone used to working in solitude, Herron has had an unexpectedly enjoyable time as script consultant – “there’s an awful lot of laughter in a writers’ room,” he says. But for the greater part of a decade, until the books took off, Herron – whose quiet, measured speech is inflected by a gentle Newcastle accent – was writing the series at nights, while commuting to London to work as a subeditor on a legal journal based, as it happens, near the Barbican. He’d be on the 6.30am train from Oxford, and back at the dining room table by 6pm to get 350 words down before the day’s end. This commitment strikes me as extraordinarily single-minded. But, he says, “I was doing it for myself; if I’d been doing it for the money I would have stopped long ago”.

Though it would be unfair to imagine that the day job had influenced the Jackson Lamb novels unduly (Slough House wouldn’t pass the most cursory health and safety inspection), it’s certainly clear that Herron’s years in the workplace have given him a deep well of material to draw on. Much of the pleasure of the books lies not so much in the thriller plots (excellent as they are) as in his conjuring of the textures and dissatisfactions of office life. “Plotting is pretty much secondary to me,” he says. “What really interests me is the characters and getting to grips with them, and them getting to grips with each other.” I hope none of us has worked in an environment so comfortless as Slough House; and yet the passive aggression over kettle use, and disgust at irksome perfumes emanating from the office fridge, are eminently recognisable.

Over this squalor, veteran agent Jackson Lamb presides – or perhaps “squats” would be a better word. He is the Falstaff of the spying world: obese in body; revolting in personal habits; gratuitously insulting in manner. Lamb is the id, perhaps, to Herron’s own deeply courteous ego. “He says things I would never say,” Herron tells me. “I look back at some of those lines and think: ‘My God, did I write that? My mother reads this stuff!’ He’s become unstoppable – I can’t have him suddenly becoming nice, or showing that he has a heart of gold – neither of which I believe, anyway.”

John le Carré gave me permission to become a writer – he showed me you could invent an entire world

Herron’s Regent’s Park and Slough House – the whole machinery and bureaucracy of his secret service – are created from a patchwork of elements, some newly invented, some drawing on previous fictions. The late great John le Carré has been an important influence: the day after le Carré’s death is announced I call Herron, curious to know if his character Molly Doran, the ferociously sharp queen of the Regent’s Park archive, draws on le Carré’s unforgettable Russia analyst, Connie. “Absolutely,” he says. “After I’d written Molly, I realised she’d come lock, stock and barrel from Connie Sachs.” Le Carré was, he says, one of those authors who “gave me permission to become a writer … He showed me you could invent an entire world, invent its language too.” Part of the appeal of the spy novel for Herron is that “authenticity” is really a question of creating a fully imagined, credible world. Unlike the police procedural novel, it’s not as if anyone’s really going to be in a position to contradict you, at least openly.

Nevertheless, Herron’s novels are fixed to reality in a certain way. If le Carré’s early spy novels reflected a cheerless postwar world full of moral uncertainty, Herron’s fictional universe is an expression of our own chaotic and friable times. Slough House is underpinned by the real Skripal poisoning case. The Catch, a recent novella picking up loose threads in the Lamb books, draws on the murky story of Jeffrey Epstein. As he says: “In the past couple of years, no matter how far you push [the story], something stupider and even worse is going on in the real world.”

One of his characters, Peter Judd, an unscrupulous, ambitious and amoral politician, seems strangely familiar. A quotation from the first book, Slow Horses, needs, I think, no further explanation: “With a vocabulary peppered with archaic expostulations – Balderdash! Tommy-rot!! Oh my giddy aunt!!! – Peter Judd had long established himself as the unthreatening face of the old-school right … Not everyone who’d worked with him thought him a total buffoon ... but by and large PJ seemed happy with the image he’d either fostered or been born with: a loose cannon with a floppy haircut and a bicycle.”

A decade and several novels on, Judd has graduated into a manipulative, cynical villain, happy to ally himself with the nationalist far right in his endless pursuit of personal power. Herron, as it happens, was a student reading English at Balliol College, Oxford, at the same time as Boris Johnson. Did you know the prime minister then, I ask? “I saw him once or twice in the junior common room. I wasn’t mixing in that kind of circle,” he says, drily. “I don’t think the Bullingdon Club opened its arms to northern comprehensive types, somehow.” Herron seems a little sheepish at the resemblance between the fictional PJ and the all-too-real BJ. “When I started,” he says, “I didn’t have a readership, so I could say what I liked and it didn’t matter.”

Slough House was finished just as the first lockdown began. Coronavirus does not feature in the book, though we learn that Britain has recently been through a shock referred to only as “you know what”, as if Brexit is, like JK Rowling’s Voldemort, too terrible to be named. “I don’t want to write a book about Covid, because who wants to read that? And the one I’m writing now won’t appear until 2022, when, let’s hope, this will all be a dim memory.” Nevertheless, he says, he’s furious about the government’s bluster, the “chest-beating” and the endless claims that Britain is “world-beating and everyone else was looking on in envy”. It’s not something he’ll address head-on, he says, “but I will find, to my own satisfaction, a way of converting into prose how angry I feel”.

When Herron began working on the Jackson Lamb series, at the back end of the 2000s, he’d already written an entire series of thrillers featuring an Oxford-based investigator, Zoë Boehm. They weren’t especially commercially successful, but “I was fulfilled, because I was doing what I wanted to do”. Oddly enough, the entire concept of the Jackson Lamb thrillers – its cast of failures and dropouts – depended on his own lack of fame and fortune. “I could happily empathise with people not having a stunningly successful career, it’s fair to say.”

For a long time I didn’t really trust the money that was coming in – I felt like someone might ask for it back

When Slow Horses, was brought out by Constable in 2010, it didn’t do well. The publisher turned down the next book. Dead Lions, and its successor Real Tigers, were published only in the US, by Soho Press. But then an editor from John Murray publishers – Mark Richards – got in touch. He wanted to see if there was a way of having another crack at putting out the novels in Britain. “He came to plead his case, took me out to lunch. He seemed a nice guy, seemed to know what he was doing. But I genuinely thought nothing would come of it – I thought he’d republish the books and they’d sink just like they always had before.”

That same year, 2015, John Murray published Slow Horses and Dead Lions in paperback. And indeed, just as Herron had predicted, “they sank without trace. But Mark kept on at it. He decided the reading public had got it wrong and he was going to keep reprinting these books until people noticed.” Eventually they did. In 2016, Herron was in a position to take four months unpaid leave from his job. After that, he resigned. A real turning point came in 2017, when Waterstones named Slow Horses thriller of the month – a full seven years after it was first published. Herron calls himself “a rescue author”. I sense, from our surroundings, that he’s not exactly flinging money about, unless he’s bought a fancy car. But no: he can’t drive, he tells me. “For a long time I didn’t really trust the money that was coming in. I felt like someone might ask for it back.” And anyway, his tastes are pretty simple. “I like books, I like music, I like food and wine – but I don’t want toys,” he says.

The 16 years of office work between the publication of the first Zoë Boehm book and becoming a full-time writer were not wasted, he says. The commute was “good thinking time … Sitting down and writing was the end product of a day in which at least part of my brain was thinking about what would go on the page.” The work itself was useful: subediting, he says, “is as good a discipline as you can have for writing prose of any kind. You learn how to treat your own stuff as if it’s someone else’s – it just becomes the material that you’re working with.” Progress was necessarily slow, “but I wasn’t in a hurry; it’s not like I had a readership knocking on the door. I worked at my own speed and the satisfaction was in the work.” What is absolutely clear to me is that Herron would have written, doggedly and enjoyably, for the rest of his life, with or without the success he has happily achieved now. “This is what I do,” he says, simply. “I’m a writer.”

• The latest book in the Jackson Lamb series, Slough House, is published by John Murray on 4 February. Slow Horses will stream on Apple TV.