Prosecutors say Murdaugh’s motive lurks in a history of theft. Can they tell the jury?

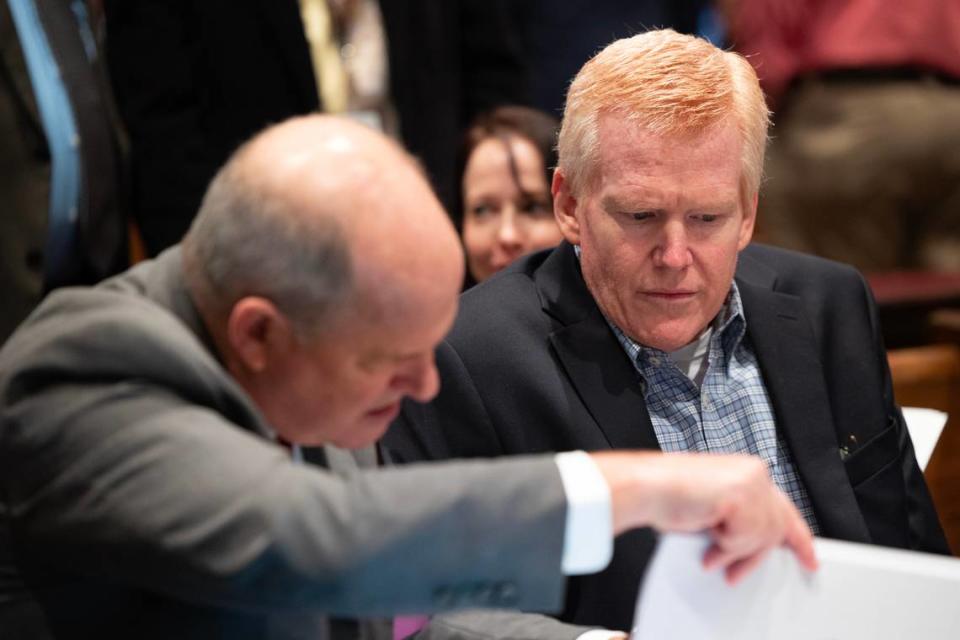

A South Carolina judge on Thursday heard gripping testimony from accused double murderer Alex Murdaugh’s longtime best friend and a top official from his former law firm about how the former Hampton attorney lied and allegedly stole from clients and fellow lawyers.

One prosecution witness, Jeanne Seckinger, a longtime finance officer at Murdaugh’s former law firm, explained how Murdaugh repeatedly violated the firm’s long history “of trust and brotherhood” with his lies and thefts of more than $2 million.

Chris Wilson, Murdaugh’s longtime best friend, wept with sadness and anger as he explained how Murdaugh used him in a 2021 scheme to pocket $792,000 in fees from Murdaugh’s law firm, in the process bilking Wilson of $192,000.

“He was one of my best friends,” said Wilson, who spent more than an hour on the witness stand Thursday, at times dabbing his eyes with a tissue. “I thought he felt the same way about me.”

Asked by lead prosecutor Creighton Waters how, sitting before Murdaugh, he feels now, a downcast Wilson replied, “I don’t know how I feel now, Mr. Waters.”

Both testified Thursday out of the jury’s presence at Murdaugh’s double-murder trial as Judge Clifton Newman mulls whether their testimony and others can be shared with a Colleton County jury as motive for murder.

Murdaugh, who hails from a prominent family, is accused of killing his wife, Maggie, and son, Paul, the night of June 7, 2021, at the the family’s rural 1,700-acre rural Colleton County estate.

He has pleaded not guilty, and faces life in prison without parole if convicted in their deaths.

For now, the 12-member jury has only heard hints from prosecutors about Murdaugh’s alleged money schemes.

On Thursday, after hearing from Seckinger and Wilson, Newman appeared receptive to the state’s arguments. He indicated late Thursday he was willing to let the jury hear information about Murdaugh’s money schemes, but said he might decide Friday how much of it could be disclosed.

Prosecutors want to introduce the financial evidence to show the jury a motive for why Murdaugh would seek to kill his own family members. Murdaugh’s attorneys, Dick Harpootlian and Jim Griffin, say there’s no connection between the murders and Murdaugh’s unraveling financial problems.

“He was burning through cash like crazy. (That) $792,000 was gone in no time at all,” Waters explained to Newman Thursday. “This is really about the fear of being about to be exposed. On June 7, at that point of time, he was out of options.”

Only by knowing the specifics of Murdaugh’s extensive embezzlement schemes — and the looming threat of disclosure by his law firm and attorney Mark Tinsley who had named Murdaugh as a defendant in a civil lawsuit — Waters said a jury would be able to understand why Murdaugh “was doing these things and why he was out of time.”

Waters told Newman he wants to introduce additional evidence to the jury that would show how Murdaugh engineered a $4 million theft from the estate of his late housekeeper, Gloria Satterfield, and how Tinsley was seeking $10 million in damages from Murdaugh at the time of the murders.

“For a jury to understand what is going on, they really have to understand the full picture,” Waters said. “When the hound is at the door, when Hannibal is at the gate, violence happens.”

Griffin told Newman Thursday the connection is illogical and should not be admissible under South Carolina’s rules of evidence, which don’t allow the jury to consider prior alleged criminal conduct.

And in any case, Griffin said, the imminent death of Murdaugh’s father, Randall Murdaugh, had already begun to generate considerable sympathy from his law partners and others, sympathy that would have delayed any investigation from his firm, which already had a long history of forgiving his financial improprieties.

And, Griffin said, Mureaugh was in the process of refinancing various properties and that refinancing would have releived financial pressures.

“It’s all just a theory,” Griffin said. “There’s no facts.”

Law firm CEO confronts Murdaugh about missing money

The state on Thursday first presented testimony from Seckinger, the chief financial officer who oversees the bookkeeping at the Parker Law Group, Murdaugh’s former law firm known as PMPED.

Seckinger testified that Murdaugh was forced to resign from the law firm his great-grandfather started because of evidence he stole millions of dollars from his law partners over a number of years. Seckinger testified that for years money had gone missing around Murdaugh, who also had a habit of charging inappropriate personal expenses.

Her testimony offered a glimpse into the inner workings of one of the Lowcountry’s preeminent personal injury firms, where partners were paid a salary of $125,000 a year before receiving what they earned from lawsuit settlements and jury verdicts.

On one occasion, Seckinger testified that Murdaugh billed a client for a private flight to the Florida Keys. But his actions at the close-knit law practice that his family founded, and where he was a well-respected and profitable lawyer, were regularly brushed under the rug after he paid the firm back.

Each December, PMPED tried to clear out all of their cash reserves in order to minimize taxes, according Seckinger, who has known Murdaugh for more than 40 years and worked at the firm since 1999. That meant that partners often would have to loan money back to the firm at the beginning of the new year so that they could cover basic operational expenses.

Attorneys were expected to turn over all fees and expenses received from clients to the firm, and all payments were expected to be made out to the firm, Seckinger testified. Not doing so would be “stealing,” she said.

At first, Seckinger said she was merely suspicious that Murdaugh was trying to hide money from a civil suit where he was a defendant. The suit stemmed from a 2019 fatal boat wreck Paul had been involved in that killed 19-year-old Mallory Beach.

It was well known around the office that Murdaugh was being sued and that the plaintiffs wanted to get a hold of his finances, Seckinger testified.

In May 2021, Seckinger’s said she grew concerned when she learned Murdaugh had not properly deposited money from a settlement, leading her to believe he was either withholding a check made out to the law firm or had the check inappropriately made out to himself.

At the time, Murdaugh claimed that he was just trying to put some money in Maggie’s name and was buying a settlement from Forge, a structured settlement company used by PMPED, as a favor to one of its executives, Michael Gunn.

Gunn, who also testified Thursday, is a principal at Forge, a structured settlement firm regularly employed by Murdaugh’s former law firm. Murdaugh is accused of directing checks to a Bank of America account he controlled that appeared to belong to Forge. It did not.

Seckinger, however, was uncomfortable with Murdaugh using the firm as a vehicle to hide his money.

“That would be wrong and we would not want any part of that,” Seckinger testified Thursday.

But in June, Murdaugh’s paralegal brought another urgent matter to Seckinger’s attention: They were missing a $792,000 fee check from attorney Wilson, who had just completed a case with Murdaugh.

While the firm had received a check for expenses, they had not received the check for fees, which usually arrived at the same time, Seckinger testified.

“At that point in time, no one was saying they thought he was stealing from the firm,” Seckinger said, adding but there was concern that he was “sheltering money from being disclosed.”

On June 7, 2021, hours before Maggie and Paul were shot to death at the family’s remote estate, Seckinger said she “made another run at finding out from Alex if we had any information (about the check).”

“He was cleaning out a filing cabinet outside his office, and he saw me and said, ‘What you need now?’ And he gave me a dirty look, not one I’d ever received from Alex,” she said.

Inside Murdaugh’s office, Seckinger said she told Murdaugh she “had reason to believe he had received those fees himself, and I needed proof that he did not.”

Murdaugh assured her he that the money was simply in a trust account because he was considering how to structure the settlement. The meeting ended abruptly when Murdaugh received a phone call that his father had been moved into hospice care.

Immediately, Seckinger said that she dropped the matter of the missing check and started talking to him as a friend.

“We quit talking about business,” Seckinger said.

Later that night, Murdaugh’s wife and son were found murdered, and the inquiries were put on hold. It also postponed actions in a civil lawsuit over the boat crash, which could have required Murdaugh to disclose financial information.

“Alex was distraught, upset, not in the office,” Seckinger testified. “We didn’t want to harass him when we didn’t think it was really missing and had a year to clear it up, so we didn’t harass him over it.”

By Sept. 2, 2021, Seckinger looked up payments made to Forge in the firm’s ledger.

She found Murdaugh had been writing checks to a Bank of America account for Forge. The account holder was Murdaugh.

The next day, Seckinger said that she and the firm’s partners, including Murdaugh’s brother Randy, convened at a partner’s home and agreed that Murdaugh needed to be terminated. When he confronted, Seckinger said that Murdaugh confessed.

“We made him resign,” Seckinger said.

Friend says Murdaugh admitted to ‘stealing’

In reality, Murdaugh had already received $792,000 from his best friend, Wilson.

In early 2021, the two friends worked together on a personal injury case that resulted in $2 million in fees, which Wilson was responsible for distributing to the other attorneys on the case.

Rather than send the money to Murdaugh’s law firm, however, Murdaugh convinced Wilson in March 2021 to write $792,000 in three separate checks to Murdaugh personally. Wilson testified he was told it was a structuring procedure he was unfamiliar with, but that he “trusted his friend” of some 30 years.

“As far as I knew, the firm was aware the the monies had been being paid to him, that he had were being put in annuities,” Wilson testified.

But Murdaugh later wired the money back to Wilson saying he had “messed up” the fee structure and requested Wilson send the full amount to the law firm, even though Murdaugh told him he could not recover $192,000. Wilson said he sent the missing money to Murdaugh’s firm from his own personal account.

Prosecutors believe the whole procedure was meant to throw suspicion off of Murdaugh for stealing funds from his law partners. Even then, Wilson remained unsuspicious of Murdaugh.

He rushed to his friend’s side when his wife and son were killed. It was only when the law firm contacted him about the money that he was told Murdaugh had been stealing from clients and the firm.

On the morning of Sept. 4, 2021, Wilson saw his old friend one final time at Murdaugh’s mother’s home, when he asked him for an explanation.

“He broke down crying,” Wilson remembers. “He told me he had a drug problem, that he was addicted to opioids, that he’d been addicted for 20-plus years or so. And he told me that he had been stealing money.”

“I was so mad, I don’t remember how it ended,” Wilson said. “He sh-- me up. He sh-- a lot of people up.”

Later that day, Wilson said he learned Murdaugh had been shot on the side of the road, in what turned out to be a botched attempt by Murdaugh to have himself shot in an insurance scheme.

“I thought for sure he had tried to kill himself,” Wilson testified.

The fight over motive

The question of the financial motive may prove to be one of the most important battlegrounds in the Murdaugh trial.

Griffin and Harpootlian have argued that it was impossible Murdaugh would kill his wife of almost 30 years or Paul, “the apple of his eye.”

Rogan Gibson and Will Loving, two friends of Paul’s who considered the Murdaughs a second family both testified Wednesday that they could think of no reason that Murdaugh would commit murder, despite claiming to hear his voice on a video taken from the kennels just minutes before the killings.

If the prosecution is able to get witnesses, including Seckinger, Wilson and Gunn, on the stand, the jury will hear the details of more than 90 different alleged alleged financial crimes across 17 different indictments. They would present what Waters has called an “unbroken chain” of alleged lying and theft as well as the cynical manipulation of friends, clients and family going as far back as 2011.

Murdaugh’s defense attorneys have strenuously objected to the introduction of this evidence. They have argued that introducing unproven allegations would violate evidentiary rules, delaying the trial and unfairly prejudicing the jury.

Griffin, a veteran white-collar defense attorney, has worked to stymie the prosecution’s efforts to introduce evidence. The defense has made it clear that they will not stipulate to allowing the evidence to be admitted and they appear to be willing to take up Newman’s challenge that every financial witness undergo cross-examination before taking the stand.

Griffin has argued that the state’s use of these witnesses violates two key evidentiary rules:

▪ 403a — preventing the inclusion of evidence that might unfairly prejudice or confuse the jury due to creating delays

▪ 404b — preventing the testimony of past bad acts unless it meets a strict set of criteria, among them a proof of a common scheme, intent or narrow definition of motive

In cross-examination of Seckinger, Griffin highlighted just how many people were involved in the law firm’s investigation of Murdaugh’s alleged theft. In many cases, she had no direct knowledge of the thefts, only what had been told to her.

Isn’t that hearsay, Griffin asked Seckinger.

“It’s not hearsay if they said it to me,” Seckinger replied, snappily.

Seckinger has previously testified to her confrontation with Murdaugh at the November 2022 federal trial of former CEO of Palmetto State Bank Russell Laffitte, who was convicted on bank fraud and conspiracy charges related to his handling of Murdaugh’s accounts, often making money transfers from client’s accounts at Murdaugh’s request.

In the small world of Hampton County, Seckinger is also Laffitte’s sister-in-law.