'I needed knee surgery after it!' The return of barnstorming musical Rent

When a new production of the musical Rent opens in Manchester this month, it will provide proof of two kinds of endurance. The first is that of the theatrical community. Social-distancing restrictions have forced the Hope Mill theatre to halve its capacity and to install plastic screens between audience members from different households. (All seats sold out within 48 hours but online streaming tickets are still available.) Meanwhile, the show’s company will be living in their own bubble of shared accommodation throughout the run. Cosy.

The other example of staying power is Rent itself, the rock musical phenomenon that updates Puccini’s La Bohème to early 1990s New York and follows a group of friends – including the drag queen Angel, the dancer Mimi and the performance artist Maureen – who are grappling with poverty, gentrification and Aids. “For many musical theatre fans, it’s a gateway show,” says Luke Sheppard, who is directing the new production. “It always celebrated inclusion so it reaches very widely across sexuality and gender identity, touching people in specific ways.”

Sheppard has no doubts about the show’s relevance, though even he was taken aback by how closely it reflects our times. On the day when a government advertisement encouraged unemployed ballet dancers to consider retraining in cyber security, the cast were busy rehearsing the scene in which Maureen rails against performance spaces being closed and replaced by Cyberland. “It was quite spooky. You only have to glance at the news to see people in the arts who’ve been left behind and are now struggling to pay the rent.”

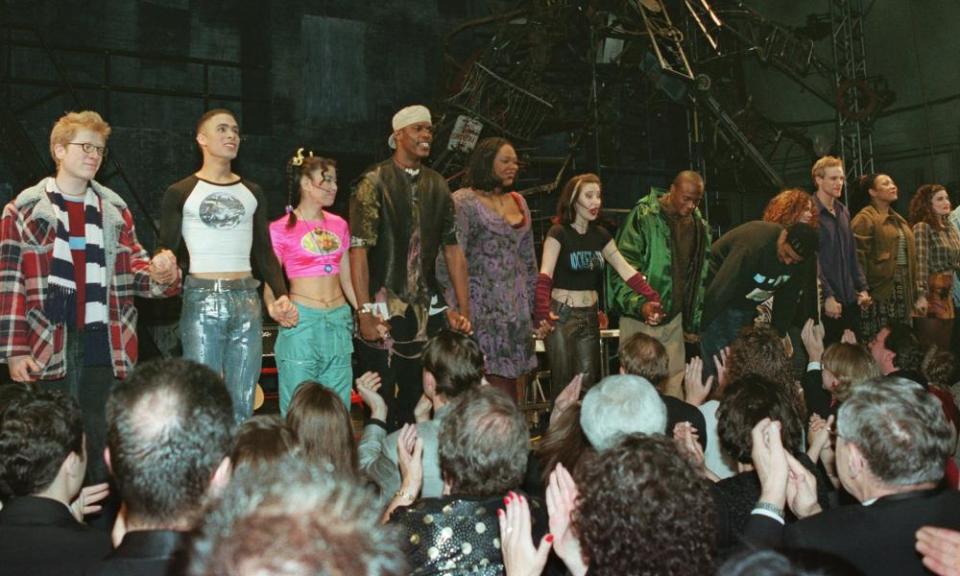

It is almost a quarter of a century since the show opened at the tiny New York Theatre Workshop with a cast that included Idina Menzel, Anthony Rapp and Taye Diggs. The circumstances of that first preview in January 1996 were uniquely tragic: the show’s 35-year-old creator, Jonathan Larson, had died unexpectedly from an aortic dissection the previous night. “It’s unbelievably sad that Jonathan didn’t get to enjoy the success of the show,” says Michael Greif, its original director.

“There wasn’t a moment that I wasn’t thinking about him,” recalls Wilson Jermaine Heredia, who won a Tony award for originating the role of Angel before reprising it on stage in London and in the 2005 film version. “I would gaze out at the audience at the Shaftesbury theatre and say to him, ‘Look where we are, Jonathan. I wish you were here to see this.’”

Daphne Rubin-Vega, who played Mimi, remembers Larson as “this lanky, curly-haired geek in dirty sneakers. Awkward-looking but adorable as fuck.” He lived in a shabby fifth-storey walk-up apartment not dissimilar to the one in the show, right down to the bathtub in the kitchen and the keys that had to be tossed down to visitors to let themselves in. “The hand-to-mouth existence was his world,” says Greif. “What was remarkable was how fully Jonathan’s heart and heartbreak were in the material. He was writing a contemporary musical and honouring a group of people he knew very well who were suffering and dying in the Aids crisis.”

The music itself felt radical, too, introducing a youthful MTV energy into a landscape dominated by cobwebbed monoliths. “It was all Andrew Lloyd Webber and Les Mis and Grease,” says Heredia. “That didn’t interest me. Whereas reading Rent and hearing the music, I felt for the first time that here was something that spoke to me and my generation. I was a club kid. I knew these characters.” Greif saw that urgency and immediacy reflected in the audience. “The crowd always skewed young,” he says. “It was pretty amazing.”

Many of the cast members felt validated by this show with diversity in its DNA. “All the reasons why I didn’t qualify to be a useful member of the theatre community became assets,” says Rubin-Vega, who is Panamanian-American. “The liabilities, the limitations, every time I’d heard, ‘No, sorry ’– they became the reason I was there.” Heredia felt the same. “Broadway was a no-go for me,” he says. “One, because I’m Latin. Two, because I’m brown Latin on top of that. But when I auditioned for Rent, I thought: ‘Even if I don’t get the part I know this is going to change musicals forever.’” I ask whether Larson knew the impact the show would have, and Heredia howls with laughter. “Oh, Jonathan knew!” he says. “Anthony was at a party with him where he introduced himself to people with the words, ‘Hi, I’m the future of musical theatre.’”

That vitality and self-belief only made his death more shocking. “Idina called in the morning to tell me,” Rubin-Vega recalls. “She was almost laughing because it was inconceivable. He was just here. How could he not be here?” It was decided that the first night’s show would go ahead as a seated reading. “We were all in shock,” says Greif, “and I wanted to let everyone simply celebrate Jonathan. I didn’t want Wilson to worry about jumping on the table in heels.”

In fact, that’s exactly what happened as the evening blossomed into a fully fledged, barnstorming performance. “That was very moving and meaningful,” says Greif. “I stood up during the song Out Tonight,” Rubin-Vega explains. “And by La Vie Bohème at the end of the first act, we were all on the tables. You can’t do that show sitting down!”

After three heaving months in that intimate space, the show exploded on to Broadway. “We got a fast pass,” laughs Rubin-Vega. “I think that was the moment I understood what ‘zeitgeist’ meant.” Rave reviews rained down along with four Tonys, six Drama Desk awards and a posthumous Pulitzer for Larson. Throughout the acclaim, Rent retained what Sheppard now calls its “joyful messiness”. There was a reason for this. “Some things in the show I was uncomfortable with, or felt were unfinished,” says Greif. “But we didn’t touch them because we’d already had those conversations with Jonathan and we knew he hadn’t wanted them changed.”

Rent ran for more than 12 years on Broadway, spawning a film version and hundreds of productions around the world. It suffused pop culture, whether it was being celebrated (in the US version of The Office, co-workers sing its big number, Seasons of Love, to their departing boss) or mocked (as in Team America: World Police, with its musical show-stopper Everyone Has Aids). It also inspired a generation of younger talent, such as Layton Williams, the star of Everybody’s Talking About Jamie, who played Angel in the UK 20th anniversary tour in 2016. “It’s a demanding show to do,” he says. “I had to take four or five weeks off and have surgery on my knees. Playing Jamie was a walk in the park after that. But it’s a great ensemble piece. Everyone in it gets a chance to shine.”

Accepting his Tony award in 1996, Heredia had said: “Here’s to a new era in theatre.” Did that come to pass? “It took a while,” he admits. “But if it weren’t for Rent, producers wouldn’t have taken a chance on In the Heights and Hamilton.” Lin-Manuel Miranda, the creator of those musicals, has repeatedly cited Rent as one of his main inspirations, and is now directing Andrew Garfield in a Netflix adaptation of Larson’s lesser-known musical Tick, Tick … Boom! “Jonathan and Lin are so alike,” says Rubin-Vega, who stars alongside Miranda in the forthcoming film of In the Heights. “They both have this incredible range of musical reference points, and they both make it look easy.”

Related: Think you love musicals? Meet the fan who has seen Les Mis 977 times

Unlike Larson’s friends and family, audiences have only ever known Rent as the work of a writer snuffed out in his prime: he was dead, after all, before the show was famous. What that means is that its seize-the-day sentiments, exemplified by lyrics such as “No day but today”, seem now to comment on his early demise, almost as if they were written with that foreknowledge. But this isn’t why people are still staging Rent today. “It’s a very healing show,” says Heredia. “People have told me that it has got them through tough times.”

Sheppard is clear about its appeal. “Jonathan Larson wanted it to be a piece about hope rather than despair. That’s one of the reasons it has been so cathartic doing it now. It offers a light at the end of the tunnel.” For Rubin-Vega, Rent is something more than just a show. “It became a purpose,” she says. “And it was the ride of our lives.”

Rent is at Hope Mill theatre, Manchester, from 30 October to 6 December. Online tickets are available.