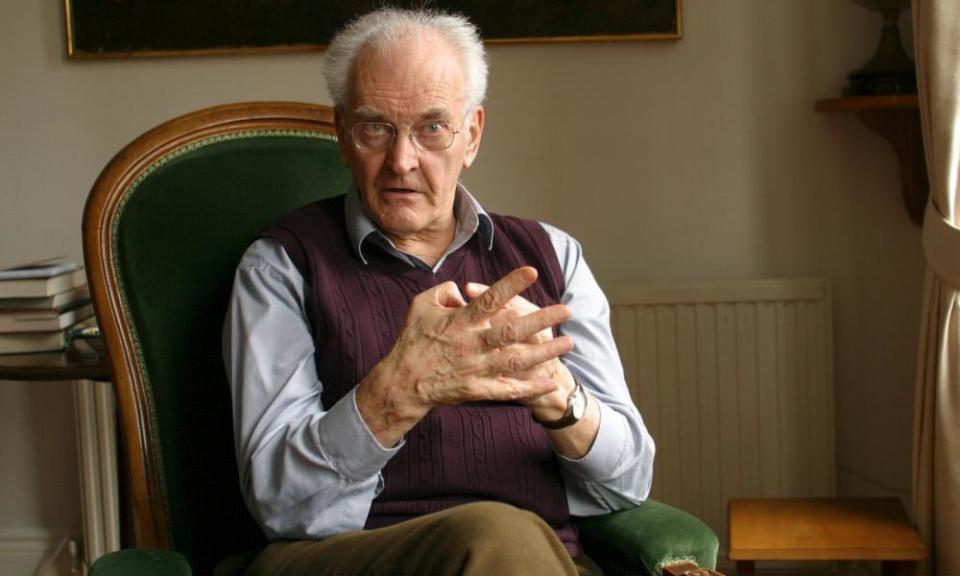

Peter Nichols probed his private life to reveal the state of the nation

Peter Nichols, who has died aged 92, once wrote an autobiography called Feeling You’re Behind. The title says a lot about Nichols in that it combined a rude joke with a sense that other playwrights enjoyed a popularity he had been denied. Yet from A Day in the Death of Joe Egg in 1967 to Passion Play in 1981, Nicholas enjoyed a rich run of success in British theatre and showed a capacity to create resonant public drama out of personal experience.

Related: Peter Nichols, playwright best known for Joe Egg, dies aged 92

The obvious thing to say about Nichols is that he relentlessly mined his private life. After a clutch of TV plays in the early 1960s, he hit the big time in 1967 with Joe Egg, which is about to be revived in the West End. It was – and still is – a landmark play in that Nichols dramatised the problem faced by himself and his wife, Thelma, of how to live with a disabled child. The difficulty, as Nichols acknowledged, was that of confronting the issue “in a way that will prevent a sudden stampede to the exit doors”. His solution was twofold: to have the characters directly address the audience and to show that domestic pain is made bearable by caustically irreverent humour. Where other dramatists might have veered towards the maudlin or sentimental, Nichols wrote a blackly funny play in which the teacher-hero typically sees God as “a sort of manic-depressive rugby footballer”.

While most of Nichols’s plays are deeply autobiographical, they exploit popular forms and at the same time offer an image of modern Britain. A classic example is The National Health, brilliantly staged by Michael Blakemore for the National Theatre in 1969 and rarely seen since. The setting is a ward in an outdated Victorian gothic hospital and Nichols uses Carry On jokes and soap-opera parody to create a microcosm of modern society. The six inmates embody everything from buoyant optimism to bilious pessimism (“this sceptr’d isle with its rivers poisoned ... beaches fouled with oil ... the sea choked with excrement”) while attended by a cynically jocular male nurse who argues that “most of the healing arts are bent if you want my frank opinion”.

Reared in the keyhole naturalism of television, Nichols was always at his best in maximising the theatricality of theatre. His mix of personal memory, popular comedy and political comment reached its apogee in his 1977 musical, Privates on Parade. The show was directly based on Nichols’ own experience, as a young serviceman, with Combined Services Entertainment in the Malaysia of the early 1950s where his contemporaries included Stanley Baxter, Kenneth Williams and John Schlesinger. This resulted in the creation of the memorably camp figure of Acting (or even over-acting) Captain Terri Dennis who signed on only because “the panto season was over and life under Clementina Attlee wasn’t exactly the Roman Empire”. But behind the gags and songs lay a serious question about whether the British military presence in Malaysia was dictated by a desire to combat communism or commercial interests.

Nichols enjoyed working on a big scale. In Poppy, staged by the RSC in 1982, he used the form of Christmas panto to explore the 19th-century Opium Wars. But Nichols could also create effective domestic drama. One of his most moving plays – though difficult to revive today for obvious reasons – was Chez Nous in which a middle-aged man is revealed to have had an affair with his best friend’s teenage daughter. Far more durable is the 1981 Passion Play, which tackles the corrosive nature of sexual infidelity. It is part of a remarkable trinity of plays on that subject – including Harold Pinter’s Betrayal and Tom Stoppard’s The Real Thing – but what distinguishes Nichols’s is his invention of alter egos for the central couple who articulate their private anxieties.

In later years Nichols fell out of fashion and, while he continued to write, many of his new plays went sadly unproduced. But he is part of the great pantheon of postwar British dramatists and, at his best, he showed zest, flair and a unique talent for fashioning national metaphors out of his lived experience.