Plaques set up around Toronto tell the slave-owning pasts of prominent historical families

Temporary plaques exposing the history of the families behind some of Toronto's street names have been spotted around the city.

But the person behind them has chosen to remain anonymous.

Essex County Black Historical Research Society president Irene Moore Davis was sent a photo of these plaques last week by an acquaintance who noticed Davis was quoted on them.

"They wanted me to be aware of it because my name was on it," she said.

The plaques give a brief history behind the name of the streets, emphasizing the relationship between the name and Black history.

In total, five temporary plaques were installed around the city, but it's unclear how many still remain.

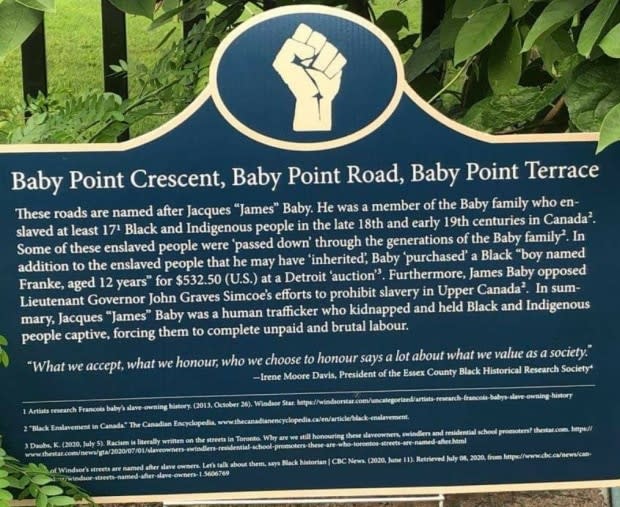

One of the plaques, installed in the Baby Point area of Toronto, reads, "These roads are named after Jacques 'James' Baby. He was a member of the Baby family who enslaved at least 17 Black and Indigenous people in the late 18th and early 19th centuries in Canada. Some of these enslaved people were 'passed down' through the generations of the Baby family."

Davis said while they were "fairly well-to-do" people, citing their involvement in the military and the Legislative Council of Upper Canada rarely recognized their slave-owning history.

"In all of that glorification of the Baby family, no one ever mentions they were slave owners," she said, adding that these slaves "were passed around like property."

She was quoted in the plaque saying, "What we accept, what we honour, who we choose to honour, says a lot about what we value as a society."

Another plaque outlines the history of the Jarvis family, explaining, in part, that William Jarvis "vehemently opposed" making slavery illegal in Upper Canada in 1793, "which meant that enslavement was gradually phased out instead of being abolished."

When Davis saw the photos of the plaques, she said she was "just amazed" and keen to find out who was behind it. She reached out to all of her friends in the Black history community but came up short.

"Nobody had any clue who was doing this," she said.

After posting the photos to her social media platforms, Davis said the person behind the plaques messaged her directly but asked to remain anonymous.

Renewed focus on systemic anti-Black racism

The plaque instalments follow a similar call for education on street names when thousands signed a petition to change the name of Dundas Street that was named after Henry Dundas, an 18th-century politician who delayed Britain's abolition of the slave trade by 15 years.

Both are part of a renewed focus on systemic anti-Black racism after the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis on May 25, putting the issue of street names and historical monuments back in the spotlight.

While there has been a lot of discussion on what to do with these street names and monuments, Davis said she thinks people will be better educated with more context and education.

"Unless it was something like a Confederate general statue, which nobody needs to see in a public place ... I'm [of] the mind that we educate people better by adding to what's already there."

From her interactions, she found people share a similar mindset.

"What I'm seeing across social media, and just in conversations with people, is that they want to see more of that," Davis said.

She suggested investing in more durable and permanent plaques to outline the historical context in different parts of the city.

At a city hall briefing in June, Mayor John Tory said he had asked city manager Chris Murray to form a working group of staff from relevant departments, including the Confronting Anti-Black Racism and the Indigenous Affairs office, to examine the issue of renaming streets in a broader sense.