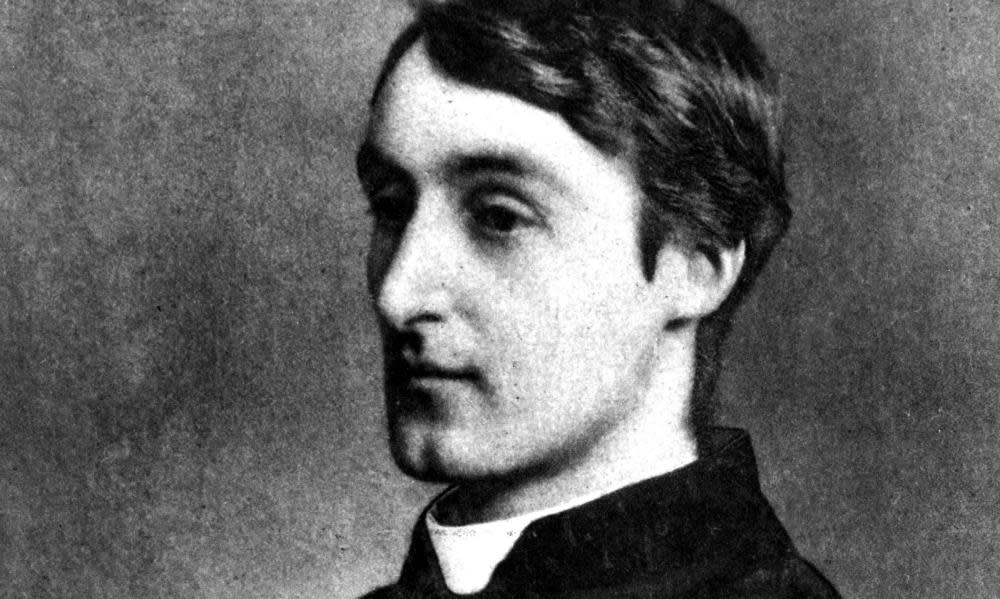

Poem of the week: Felix Randal by Gerard Manley Hopkins

Felix Randal

Felix Randal the farrier, O is he dead then? my duty all ended,

Who have watched his mould of man, big-boned and hardy-handsome

Pining, pining, till time when reason rambled in it, and some

Fatal four disorders, fleshed there, all contended?

Sickness broke him. Impatient, he cursed at first, but mended

Being anointed and all; though a heavenlier heart began some

Months earlier, since I had our sweet reprieve and ransom

Tendered to him. Ah well, God rest him all road ever he offended!

This seeing the sick endears them to us, us too it endears.

My tongue had taught thee comfort, touch had quenched thy tears,

Thy tears that touched my heart, child, Felix, poor Felix Randal;

How far from then forethought of, all thy more boisterous years,

When thou at the random grim forge, powerful amidst peers,

Didst fettle for the great grey drayhorse his bright and battering sandal!

Gerard Manley Hopkins wrote this poem in 1880 to commemorate the death of Felix Spencer, a Liverpudlian farrier who died from pulmonary tuberculosis. The suggestion that the name-change from Spencer to Randal alludes to the ballad Lord Randal is an interesting one: Lord Randal was poisoned by his sweetheart, while Felix Randal fell foul of the toxic environment of poverty. But it’s equally likely that the serendipitous rhyme with “sandal” might have occurred to the poet as he played with possibilities.

Hopkins presents his priest’s role as a great deal more significant than the “duty” remarked in the first line. That casual twist of the sentence into a question - “O is he dead then?” - conceals the strength of the reaction, as if an embryonic lament (“O Felix Randal the farrier is dead!”) had been revised to a coolly surprised comment to a colleague. But this effect is momentary, before the steep plunge into impassioned personal recollections. A doubled lamentation, “Pining, pining…”, seemingly extends from the broken-spirited parishioner to the mourner.

The emotions driving the poem are complex. Physical admiration, possibly attraction, is clearly present in the second line with its unexpected alliterative jolts – “his mould of man, big-boned and hardy-handsome”. Alliteration is a Hopkins signature, of course, but it seems especially resonant in this poem - plainly audible, but never intrusive. One reason must be the accentual syllabic meter that carries the sonnet along almost in defiance of Petrarchan symmetry, allowing echo-room in the extended line for all those sound effects. More importantly, it’s rooted in context; emotional turmoil as well as the noise and heat of the farrier’s days “at the random grim forge” are implied.

Hopkins knows exactly when to flatten and simplify his diction. Again in the second stanza, as in the poem’s first line, the tone is quieter, more detached: “Sickness broke him. Impatient, he cursed at first, but mended /Being anointed and all…” The qualifier “and all” has a colloquial flavor, at least for modern readers – as does “all road” in the fourth line, meaning “any way”. There’s a very subtle hint that Felix Randal’s own idiom has infiltrated the voice of the narrator. On the other hand, the priest seems to be speaking in the drier commentary of the ninth line: “This seeing the sick endears them to us, us too it endears.

The Holy Sacraments deliver salvation, and the poem emphasizes their transformative effects on the parishioner, the learning of what is so gracefully phrased as “a heavenlier heart”. At the same time, the priest is fatherly in a literal way; in lines 10 and 11, there’s a direct tenderly empathetic voiced addressed to “child, Felix, poor Felix Randal” .

Hopkins welds priest, father and perhaps doctor into his persona. The reference to the “fatal four disorders” suggests a medical diagnosis based on the ancient concept of the four humours: it was thought necessary that the four – blood, yellow bile, black bile and phlegm - remain in balance to ensure human health. In its symbols and textures, the poem seems at times a synthesis of the four elements - fire, air, earth and water – that were said to correspond to the humours. Heat and air are the elements of life and livelihood, contrasting with the weight of impending death and the flowing of tears. Above all, Hopkins reveals the totality of his human response to suffering. The poem gathers up the professional roles into an enormous expression of empathy, and seizes an unforgettable image of life and power from the ashes of decline.