Out West review – compelling trio of dramas reframes place and race

The monologue became a necessary staple over the lockdowns, reflecting pandemic angst and isolation back at us with social distance built in. Here it is again in three discrete short dramas directed by Rachel O’Riordan and Diane Page that speak of the sinister quiet of lockdown and of belonging, identity and race, like a delayed reaction to the past year.

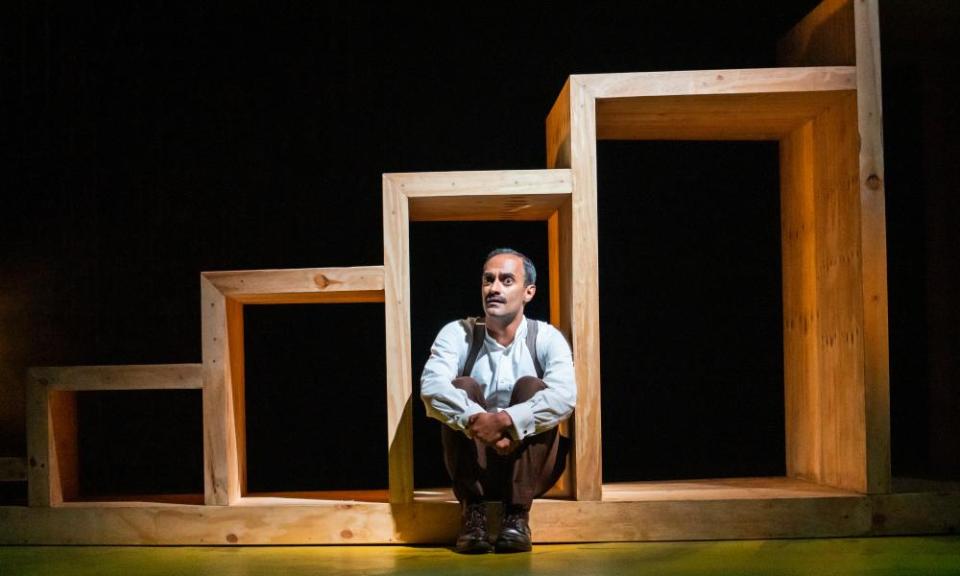

For all its familiarity, the form seems transfigured on the big, black canvas of this stage, bare but for Soutra Gilmour’s freestanding staircase structure and with subtly stunning lighting from Jessica Hung Han Yun. It has the curious effect of making the monologues appear bigger, too, holding the room with the force of each voice.

Gandhi makes his way to London as an 18-year-old in Tanika Gupta’s The Overseas Student. He is suited and booted, looking every inch the consummate Englishman on arrival in 1888. Gupta’s story begins before the starting point of Richard Attenborough’s award-winning biopic and is a part of his tender early life less well known to some.

He is forever hungry, unable to find vegetarian food, and his cultural alienation bears some shades of Sam Selvon’s The Lonely Londoners. But – crucially – he comes from a wealthy family and is a man of privilege even with this outsider status, taking elocution lessons and mixing in “society”.

The monologue’s complexity lies in these intersections of identity and there are endearing moments that capture Gandhi’s loneliness, with political and spiritual awakenings, too, but the script feels like a character study more than a story. What lifts it is Esh Alladi’s glittering performance; he fully inhabits his character, emanating emotion and intelligence.

Simon Stephens’s drama (with collaborator Emmanuella Cole), Blue Water and Cold and Fresh, is the highlight of the night. Featuring a man addressing his late father, it builds power by inches, keeping its powder dry until the very last, eviscerating moments, which shift the molecules with their force and gives the drama its terrible, final shape.

Tom Mothersdale plays a white history teacher in a mixed marriage, walking the streets of London in lockdown (“It’s like the whole city has been evacuated”). He visits various houses in which his father lived, and drops clues about their troubled history (“I’m not sure how much I liked him, my dad”).

As a monologue it feels impressionistic and ambling at first, refusing to settle on to certain ground: is this a story about an unresolved father-son relationship, the way we reshape history, or mixed marriage and white guilt? There is a particularly stinging description of the white, well-heeled, Instagram-friendly contingent at a BLM march in the summer of 2020. For a while, it seems to veer into territory similar to Stephens’s Sea Wall as a story of mourning, but moves on again.

The play withholds its central intrigue too consciously, perhaps, and this is a frustration until the payoff at the end when everything, including the seemingly whimsical title, becomes clear. Mothersdale’s performance creeps into brilliance, too.

The end of that monologue and one – savage – line in it has a visceral effect, freezing the air in the auditorium. But Roy Williams’s Go, Girl thaws us out with the story of Donna, winningly played by Ayesha Antoine. She is a security guard and proud mother, who has humour, sass and everywoman heroism.

Related: Triple threat: Out West at the Lyric Hammersmith – in pictures

Donna begins by remembering the proud day she was chosen to sing for Michelle Obama at her school. A fellow pupil – now successful photographer – takes a picture that reframes the moment as a portrait of black, working-class woe (“She made us look like we were suffering”).

We wait for the meaty drama around this to be unpicked but it swerves away from the intriguing setup to alight on a local hero story involving Donna and her daughter. If this feels like a missed opportunity, it lightens the mood with gentle comedy and feelgood vibes, and pleases the crowd, too.

At the Lyric Hammersmith, London, until 24 July.