Why I'm addicted to self-help books

The first self-help-adjacent book I ever read was called Every Girl’s Handbook. My mother bought it for me when I was 12 (coincidentally, at exactly the same time that I discovered Agatha Christie) and it was packed full of useful information about makeup and what star signs I might be compatible with for both friendship and romance. I loved that book, loved in particular the idea of a book designed to help me, and studied it with great passion and commitment night after night. I did not, however, become a regular reader of self-help books at that point in my life – after all, I had all of Christie to read, and then Ruth Rendell. I devoted most of my next two reading decades to crime fiction.

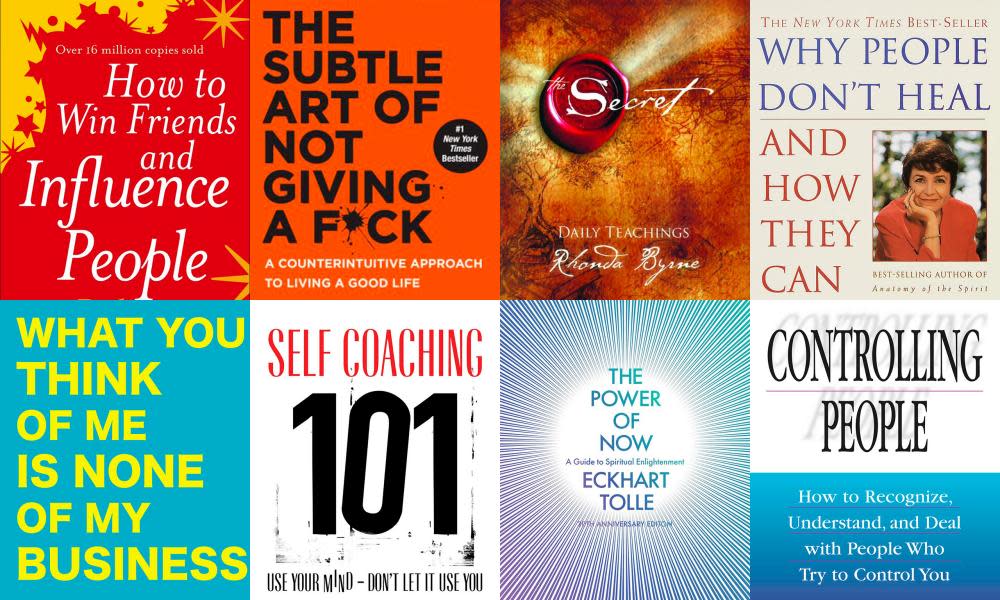

I might never have returned to the self-help genre, or become an avid fan of it, were it not for an experience I had in Crete in 2003. I had agreed to teach a creative writing course in Loutro, a rocky village on the Libyan sea, for a company called World Spirit. In those days I would have described World Spirit as a “new agey” outfit. There was another course running at the same time as mine, and its tutor was a guru. Other people called him that and it was also how he described himself. I caught a ferry with him on the way home. He was fascinating, and spent the ferry ride explaining in the most charming and entertaining way that everything I had ever believed and the entire way I viewed the world were wrong. Meeting him inspired me to read his book, which proved far too new agey for me. Despite coming to this conclusion, I was fascinated by the guru and what he represented. And people were talking, at the time, about another spiritual book called The Power of Now, by Eckhart Tolle, so I thought I’d give it a try.

Related: Oliver Burkeman interviews Eckhart Tolle, author of The Power of Now

It’s no exaggeration to say that The Power of Now changed my life. Like the Ferry Guru’s book, it was definitely new agey, but if you took away the spiritual stuff (I wanted to do this at the time; I wouldn’t want to now), what remained was a radical new way of looking at the world. Thanks to Tolle, I learned that I would be entirely mistaken if I were to judge, for example, my friend Zelda’s recent actions negatively and imagine I’m a better person than her. As Tolle puts it: “If her past were your past, her pain your pain, her level of consciousness your level of consciousness, you would think and act exactly as she does. With this realisation comes forgiveness, compassion and peace.” (I later wrote a self-help book of my own, called How to Hold a Grudge, that is aimed at solving the conundrum of other people still massively annoying us even once we know that they’re doing their best and that we are in no way superior to them.)

Another vital lesson I learned from Tolle was that it’s the stories we tell ourselves about events that cause all our pain and suffering, not the events themselves. All happenings and events and facts are neither good nor bad, neither happy nor unhappy, Tolle argues. For instance, if your husband fails to turn up for your 20th wedding anniversary dinner, you might tell yourself the story: “He doesn’t care. He doesn’t love me any more. I don’t matter to him.” And if you believed that, you’d feel terrible. Tolle points out that if we eschewed interpretations and instead stuck to the simple facts, the only truth would be: “A woman arrived at a restaurant at 7pm, and a man did not” – and there’s nothing upsetting about that statement.

I read all about abusive relationships, psychological vampires and women who love too much

I found myself thinking about everything differently and creating much less suffering for myself, and I wondered what other books might seriously help me improve my life. Soon I was reading every self-help book I could get my hands on. I learned about “emotional incest syndrome” – which can happen when a parent enmeshes mentally with their child and trains him or her to feel responsible for the parent’s emotional state and wellbeing. I had encountered many instances of this in real life (haven’t we all?) but I had never heard it named or anatomised before. I read a fascinating book by Patricia Evans called Controlling People on a plane to New York. Evidently the subtitle – How to Recognize, Understand, and Deal with People Who Try to Control You – was too small to be visible to my fellow passenger, who leaned across the aisle and said: “Hey, is that good? I’d love to be able to control people! Does it teach you to do that?”

I gulped down books about narcissism (“Oh, so that’s what’s wrong with Fred/Bill/Gordon – now it all makes sense!”), toxic partners, spouses, bosses, siblings, parents, children and hairdressers. I read all about verbally and emotionally abusive relationships, psychological vampires, energy predators, women who love too much, men who wipe down kitchen work surfaces too infrequently, and how and when to care less. I read a book by Caroline Myss called Why People Don’t Heal and How They Can, and many other books about the connection between physical symptoms and psychological states. For a few weeks I stalked around the house muttering: “Aha! So that sore throat I had yesterday was caused by my inability to stick up for myself when Lucinda was having a go at me!”

Many of these books, including The Power of Now, have a lot to say about how our egos always want to be right … and yes, that’s obviously true to an extent, but personally I find nothing more exciting than discovering that I’ve been massively wrong in some aspect of my thinking, and that I can start to think in the opposite way and achieve an opposite – and preferable – result. Whenever I have these moments, they land on me with the force of an amazing and delightful twist in a crime novel. If I were Zelda (not her real name, by the way), exactly as she is, I would behave as Zelda does. I would be unable to choose to do otherwise. Amazing! My thoughts and beliefs, not anyone else’s behaviour or actions, cause my feelings, and I can always change my thoughts if I want to. Eureka!

I fully understood that there was a strong chance that some of the books I read might be nonsense, but that only made my adventures in self-help all the more exciting. With each new book I thought, either this book will be right and I’ll learn something amazing and life-changing, or it’ll be dead wrong and I’ll be able to prove it and still learn something, only in a different way. I treated each book I read as if it was full of clues – and as someone who also loved mysteries and Agatha Christie, I loved clues and solving mysteries more than anything.

I started to buy self-help books I had no need for: How to Stop Binge-Drinking Vodka and Healing Emotionally After Being Crushed By a Falling Hippo. It turned out some of the concepts that are key to giving up vodka are also helpful if what you want to give up is smoking – that was definitely a problem I had in my 20s, and one that I have chosen to reintroduce into my life many times since. I think the last time was … ahem, two days ago. Self-help book addicts understand, you see, that not all problems get solved or stay solved, and that this, crucially, does not mean we shouldn’t bother with self-help books. On the contrary: it means we should read more of them, and different ones, and examine all the problems from every possible angle. Let’s face it, if the troublesome issues created by our human brains (the only culprit, always) are sticking around, then of course we need a constant supply of suggestions about how to deal with them.

Two years ago, I discovered the best and most helpful self-help content of my life so far: American life coach Brooke Castillo’s Self-Coaching Scholars programme, and Castillo’s book Self Coaching 101. Castillo, and her organisation, The Life Coach School, teaches that all circumstances are neutral – neither good nor bad – and that it’s never a circumstance but always a thought that creates our feelings and therefore our actions and our life experience. And the good news is: we can always choose what thoughts we want to think, on purpose and keeping in mind a particular feeling or result that we’d like to aim for.

This has worked brilliantly for me – so brilliantly that I’m now evangelical about Castillo’s approach. For example, I used to be resentful of the teacher who told my son, “I don’t care if you pass or fail your GCSE”, having first threatened to expel him from the same GCSE course after he missed an end-of-year exam that no one knew anything about because the school had sent out a timetable on which that exam did not appear. Now, whenever I think about that teacher, I grin and feel proud – because what first springs to mind is the massive breakthrough I made when I realised that what I wanted more than anything, in relation to her, was to “return her model” and not be affected by it. (If you don’t know what that means, then you’d probably benefit as much as I have from joining The Life Coach School’s self-coaching scholars programme.)

Now, to return to my copy of How to Stop Binge-Drinking Vodka. Obviously I can’t and won’t buy or read a book about giving up smoking because I don’t really smoke. Just every now and again. Look, stop judging me, OK? Or actually, judge me all you like, because I’ve just bought a fascinating book called What You Think of Me Is None of My Business …

• Happiness, a Mystery: And 66 Attempts to Solve It by Sophie Hannah is published by Profile/Wellcome Collection. To order a copy go to guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.