How the 1973 Battle of Versailles Changed the Course of Fashion History

Donna Karan called her “the mother of the industry.” Mussolini once reportedly called her “a bitch,” but that's neither here nor there. If there's one title fashion publicist Eleanor Lambert earned, it's “legend.” She created New York Fashion Week, the Met Gala, the International Best Dressed List, and the Coty Awards over the course of her iconic 75-year career.

But, arguably, Lambert's pièce de résistance was the Battle of Versailles fashion show, the day that American designers made the rest of the world feel their presence, arguably for the very first time.

The November 1973 event was made possible by the meeting of Lambert and Palace of Versailles curator Gerald Van der Kemp, who was seeking opportunities to fundraise for palace renovations. The once-immaculate compound of Louis XIV had seen better days and needed restorative work. Eleanor proposed a dinner and fashion show that would feature both French and American designers. At the time, the French were the only designers who seemed to matter in the industry. They were the couturiers, the trendsetters. Everyone else, Americans included, just followed their lead. So the narrative went until the Battle of Versailles.

The American representatives were Oscar de la Renta, Bill Blass, Anne Klein, Halston, and Stephen Burrows. (Anne Klein was accompanied by her assistant, a 25-year-old Donna Karan). The French camp consisted of Yves Saint Laurent, Hubert de Givenchy, Pierre Cardin, Emanuel Ungaro, and Christian Dior’s Marc Bohan.

No one considered the possibility that the Americans could out-show the French.“Everyone thought this was a joke,” fashion expert Marcellas Reynolds told InStyle.

The day preceding the show was reportedly a bit of a mess for the Americans. The French were taking up all the rehearsal time, and working conditions in the decrepit palace were less than ideal. The American set designer had prepared using inches rather than centimeters, so the designers from the states were left with useless backdrops that didn’t fit the space. There were also warring designer egos and a Halston tantrum that allegedly ended with both him and choreographer Kay Thompson walking out of the rehearsal. Liza Minnelli, who had come to perform during the show, saved the day by giving a rousing speech to the effect of “the show must go on.”

And go on it did–with Princess Grace of Monaco, Elizabeth Taylor, and Andy Warhol in attendance. Josephine Baker opened for the French, who proceeded to put on a two-and-a-half-hour performance. They had an orchestra, more than one live rhinoceros, and elaborate 17th century-inspired sets. It was grandiose and opulent, but overly formal. The focus didn't seem to be on the clothes or the models, but on showing off the resources they put into the project. “The French had a lot going on onstage but it was much more rooted in tradition and in history. They were aiming for something Marie Antoinette would have recognized,” The Washington Post fashion critic Robin Givhan told Harper’s Bazaar.

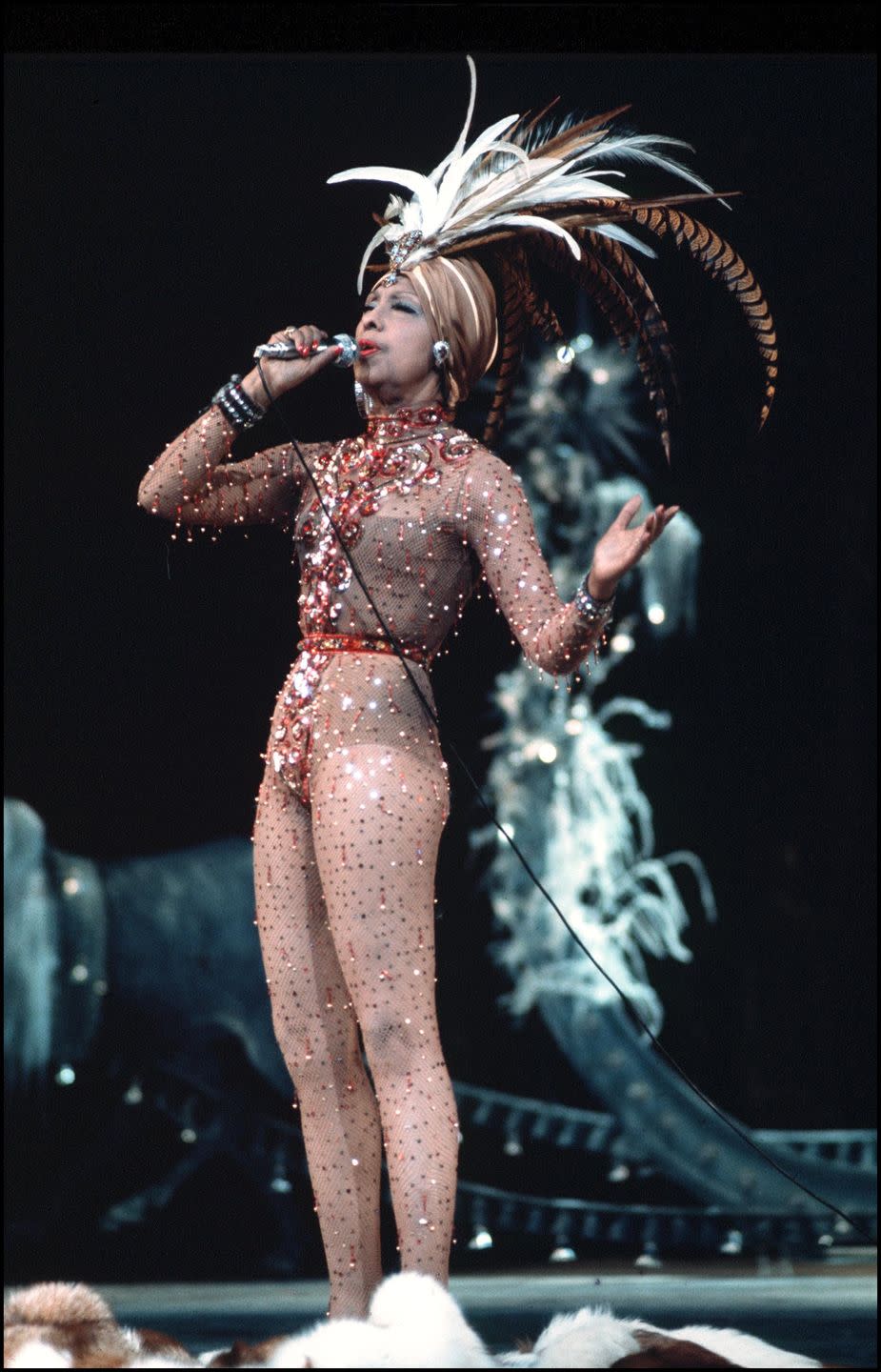

If the French show had the stale energy of an antiquated opera house, the Americans’ had the energized zing of a Broadway debut, in part thanks to Minnelli. One of Halston’s closest friends, Minnelli had recently won an Oscar for her role in Cabaret. She was the common thread throughout the American show, opening and closing each of the five designers’ segments. The lack of lavish sets emphasized the performances and, of course, the clothes. They utilized dramatic lighting and music, and had the models dancing and voguing. “The American segment pulsed with the vibrancy of the groovy disco era, and a more liberated view of femininity,” Women’s Wear Daily explains. Compared to the lengthy French segment, the Americans’ 30-minute portion was so captivating that the audience threw their programs up in the air not once but twice.

The Americans were unanimously victorious. The next day’s headline for Women’s Wear Daily read, “Americans came, they sewed, they conquered,” and the fashion world was permanently changed that snowy November night.

By many accounts, the Americans’ inclusion of Black models like Pat Cleveland, Alva Chinn, Billie Blair, and Bethann Hardison was what put them over the edge. Their presence was surprising for the time, and they stole the show. According to Cleveland, the careers of many American models, and Black American models in particular, were set on an upward trajectory from that day forward. “After [Versailles] they couldn't get enough of those girls,” Cleveland told InStyle. “It was mostly 7th Avenue girls that were coming to Europe after '73, and they were very welcomed. Things were changing. It all had to do with the music, dancing and the fun that people were having. It brought a liveliness to everything instead of just being in a couture house that was very silent; ladies having tea and looking at girls walking around the room.”

“So much of what happened at Versailles was really a reflection of the times,” Givhan, who authored a book about the event, said. “It was a reflection of what was going on politically and socially in terms of race relations. The Americans emphasized ready-to-wear, sportswear, and fashion as a kind of entertainment and a women's freedom to choose her own style of dress.”

Following the event, American designers’ sales started to boom abroad. Givhan said that, while it was an accomplishment for those involved, the true beneficiaries were the designers that came after the five at Versailles. “So much of the stress of Versailles for people like Oscar de la Renta and Bill Blass was this feeling that they had to prove themselves worthy of Paris,” she told Harper’s Bazaar. “I think for the designers who came after them, they were freed of that pressure… I think they are so freed of that and they have such a sense of pride of the importance of an American point of view. I think one of the reasons Alexander Wang can work at Balenciaga is because of the kind of weight the Versailles show lifted from the American fashion industry, but also the transformation that happened on the French side in terms of the respect for what the Americans were doing.”

The energy of the fashion industry shifted that day. The Americans won, and nobody really lost.

You Might Also Like