Absolutely Deranged Study Says Swallowing Makes You Happy and Is Why You Overeat

Every now and again, we get news of a scientific breakthrough that makes us want to put our heads through drywall — and this is one of them: researchers have determined that the happiness we derive from swallowing is what keeps us eating more (and more) of it, not from food's aroma, or taste, as you might expect.

Yes, you read that correctly: You keep eating more because your brain loves to swallow.

Start with why you're excited to eat in the first place. A constellation of indicators driven by flavor, aroma, and hunger cause us to take that first bite. But after that?

In what may be the greatest ad for Ozempic nobody could've seen coming, a paper with the catchy title of "Serotonergic modulation of swallowing in a complete fly vagus nerve connectome" was published last month in the journal Current Biology, to figure out the neurological process that keeps us, for lack of better poetry, NOMing back for more.

While reasonable hypotheses such as "Have you ever only eaten 1/15th of a cheesesteak?!" and "What kind of serial killer-grade psychopath only eats one french fry?!" went tragically untested, a substantial conclusion was somehow reached:

We identify a gut-brain feedback loop in which Piezo-expressing mechanosensory neurons in the esophagus convey food passage information to a cluster of six serotonergic neurons in the brain. Together with information on food value, these central serotonergic neurons enhance the activity of serotonin receptor 7-expressing motor neurons that drive swallowing.

By which they mean: The moment food moves from your grill past your gullet — technically, your esophagus — your brain releases a hit of serotonin, a.k.a. the "feel-good" hormone.

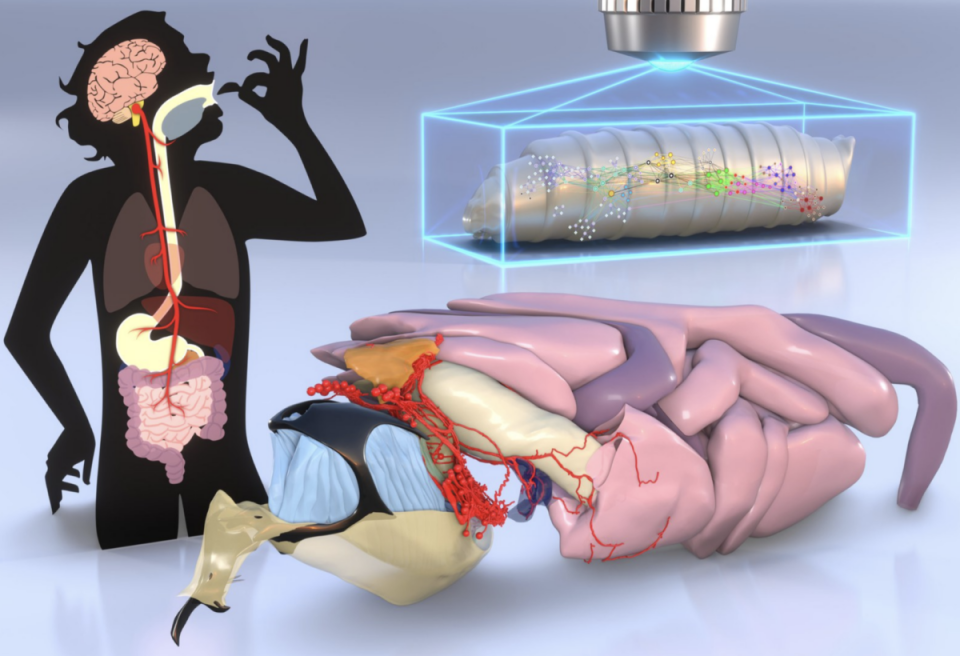

Seeking to figure out how your stomach interacts with your brain when you're digesting food, an international consortium of scientists set out on this adventure, armed with an electron microscope aimed at the larvae of fruit flies — who have somewhere between 10,000 and 15,000 nerve cells — after splitting them into "razor-thin slices." This is how they were able to get a closer look to see how their nerve cells work in tandem with one another during the digestive process.

For a visual reference, please enjoy the art used for the University of Bonn press release, which somehow accurately conveys the entire thing:

Masterful. But that's not all! The researchers did indeed find something significant, which was what they called a "stretch receptor" in the esophagus — a nerve signal that's fired off to the brain when the esophagus is processing food. If this all sounds utterly useless at face value, we're relieved to tell you that somehow, it's not. In fact, it could be extremely useful information. Per the Bonn press release:

"If [that "stretch receptor"] is defective, it could potentially cause eating disorders such as anorexia or binge eating. It may therefore be possible that the results of this basic research could also have implications for the treatment of such disorders."

In other words, if this research does path to humans like the researchers suspect it does, then there could be implications involving helping identify — and maybe, one day, reactivating — those receptors which may be broken in those with eating disorders, helping solve those problems.

It's yet another example of the kind of human behaviors we believe are a matter of choice, when they're just part and parcel of brain chemistry.

Until then, the next time you're being chided for having that extra french fry, just remember: It's not nearly as much a matter of self-control as you've probably believed it to be. If nothing else, take it as a way to be more forgiving to yourself. After all, there are far more bitter pills to (ahem) swallow. The only problem is that they might make you want to eat more of them.