Ai Weiwei Talks ‘Zodiac,’ AI and His Beating Heart

Ai Weiwei welcomes a recorded interview.

The Chinese-born dissident artist, documentarian and activist has instigated the Chinese government with his work and words over its views on democracy and human rights. Interdisciplinary in his talents, he works in art, sculpture, filmmaking, graphic novels and architecture.

More from WWD

K11 Appears to Be Revamping Guangzhou Mall With Gucci, Chanel Shoe Boutiques

Etsy's Gifting Survey Unwraps the American Psychology of Gift-giving

Report: Chinese Luxury Market to See 'Solid Double-digit Rebound'

Given that, he affirmed that is better not to leave anything to chance at the start of an interview Wednesday afternoon at his publisher Penguin Random House’s midtown offices.

Those who may not recognize his name would likely know his work. He designed the “Bird’s Nest” stadium, the lattice-like structure for the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics with the architectural Swiss firm Herzog & de Meuron.

One of his latest projects is “Ai vs. AI,” a public art project in London’s Picadilly Circus, where for 81 days he poses a question to artificial intelligence. The number is not random. After investigating government corruption and cover-ups, the artist was arrested in China in 2011 for “economic crimes,” imprisoned and held without charge for 81 days. In the time since he was allowed to leave China in 2015 and travel internationally, he has lived in Europe with his family.

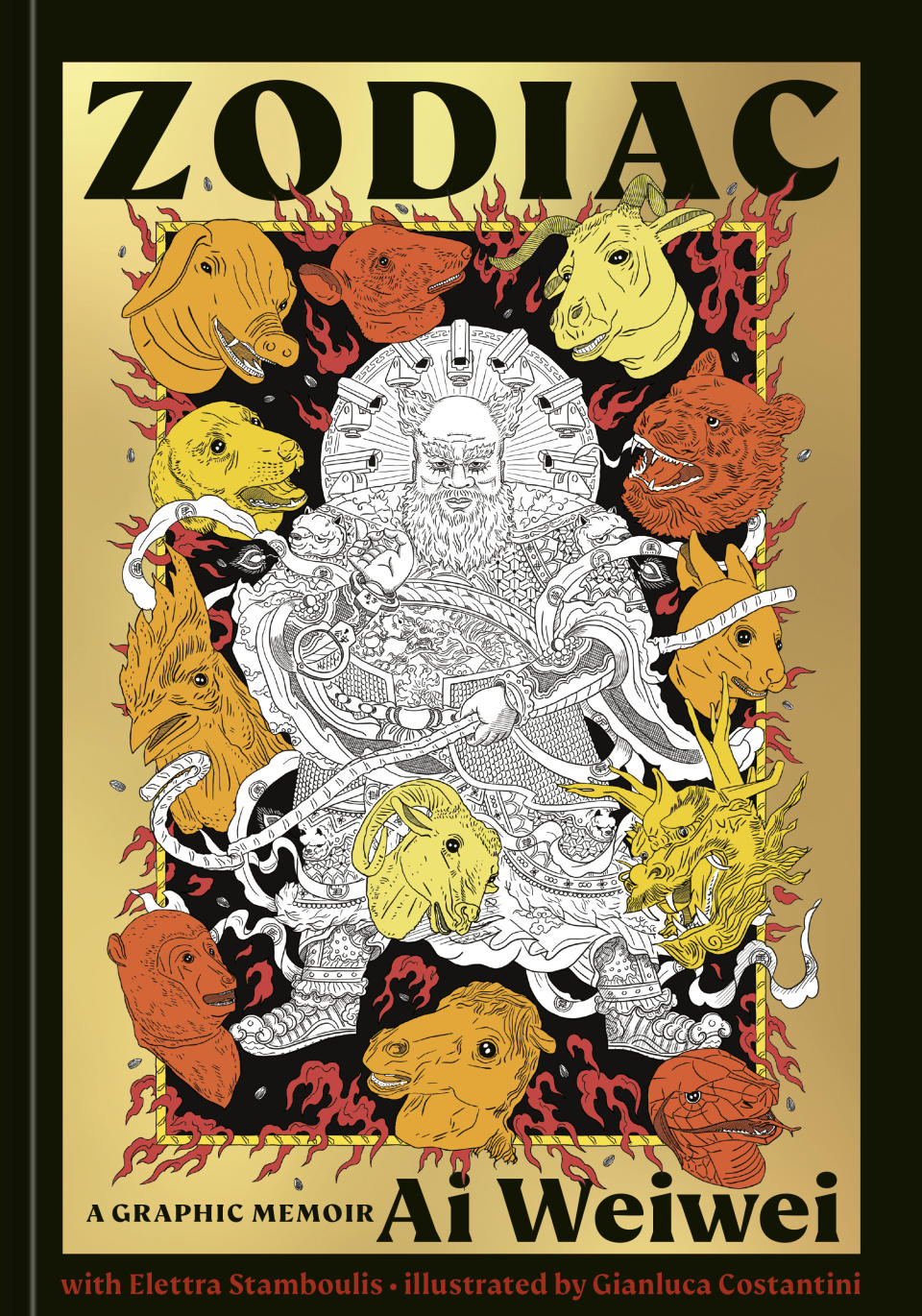

New York City is familiar territory for the creative, who lived on the Lower East Side in the ’80s and early ’90s. After a Q&A Tuesday night at Town Hall and a stop at National Public Radio Wednesday, Ai Weiwei spoke with WWD about his new book “Zodiac, A Graphic Memoir,” AI, building a massive structure without nails and his beating heart.

WWD: Do you enjoy this portion?

Ai Weiwei: I would say, “Yes.” It’s a new approach, because we always have to think about how to give a narrative to personal history. And there is so much that relates to the backdrop of culture, political activities and art. This creates some kind of blanket for the textures and the colors of life.

WWD: How do you even start to write a graphic memoir with so much to draw from?

A.W.: I started because of social media. I am quite active on social media. All my activities and images are [posted] there so it was easy for my collaborator to gather all the information to make the book possible. There are not really a few favorite elements. Yes, it’s tons of material. But it’s just a reflection of when I was a child. There weren’t any books — just some little graphic books for children. So we read about the revolutionary stories. The story was propaganda mostly of the political ideologies, but still the drawings can make it very touching.

WWD: But many see propaganda art as true art in itself.

A.W.: It is, it is — it has concept and expression and it tries to communicate. So they have strong art intentions at least.

WWD: How can artists be most effective in these rocky geopolitical times, where it seems things are only going to intensify?

A.W.: That’s a question people often ask. Personally, I think my response is through my art. But on the larger scale, artists in general are not equipped to give some kind of political argument, because in the schools, they have been teaching this kind of old method. Some even think, “Art for art’s sake” or some kind of abstract ideas. But my art is more related to humans’ emotions and activities.

WWD: Do you think art has become too politicized?

A.W.: No, I think art helps to present very little of the political reality. You cannot think of too many. It’s not possible.

WWD: There are artists who are trying to draw attention to police brutality and all sorts of issues that are affecting the world.

A.W.: Well, you have the intention. But you might not necessarily make your concept or message [carry] through, because it has to be successfully expressed to have some effects.

WWD: Wouldn’t that be subjective, based on who is looking at the art, since everyone reads it differently?

A.W.: That’s true. It really very much depends on who is looking at it. But who is looking at it is also a result of how successful the artist’s work is.

WWD: How do you decide on the questions for the “Ai vs. AI” project in London?

A.W.: I am trying to ask questions that are kind of perfunctory, or genuine questions that are always asked like, “Who am I?” or “Is art worth being collected?” I give those to AI to answer, but also I answer them in my own way. So sometimes it’s a quite different answer.

WWD: Do you think it’s funny or irksome that AI is similar to your name?

A.W.: It is funny [laughs], yeah, but it happened that way.

WWD: What are you eager to do that you haven’t had the time to get to?

A.W.: Too many things — I have a lot of bad ideas that I want to make happen. Everything makes me come up with some ideas.

WWD: How did being incarcerated change your view and creative process?

A.W.: Everything has an effect on me and impacts me. It’s like walking in a crowd, you have to move. You can’t just stop somewhere. It’s very much like driving.

WWD: Do you like to drive?

A.W.: I never learned how to drive. I don’t have a driver’s license. But whenever I am sitting in a car, I appreciate that someone knows how to drive.

WWD: What strikes you about how New York has changed since you lived downtown in the ’80s and early ’90s?

A.W.: New York is something that you cannot describe. It’s a total experience — some of it above-the-ground and some of it below-the-ground with the subway. It’s fantastic. It’s a human theater. It is more powerful than any art form. It’s deeply impressive. But of course, New York can be crazy. It can be quite dramatic, where people have super [amounts of] power and also masses are trying desperately to survive.

WWD: Did you live in the East Village and go to Parsons School of Design for a year?

A.W.: I lived on the Lower East Side. I went to Parsons for half of a year. I kind of liked Parsons but I couldn’t get a full scholarship. I had to create. But it was a good decision that I was thrown out. In New York, you learn more on the streets than going to school. It’s probably the only city [to do that].

WWD: It’s also hard to define what you learn on the streets.

A.W.: Yeah, it took me 20 years to define it. I think my life served no purpose at that time. It’s kind of frustrating, when you’re young and you have such confidence, but at the same time you think your life is useless. It was only 20 years later that I can say that my experience has started to benefit me.

WWD: Do you think about your purpose often when you are working?

A.W.: Not often, but my work includes too many things — films, documentary films, doing interviews, architecture and so many other things.

WWD: Beyond that, though, there are so many messages interlaced into all of those things.

A.W.: That must be. Everyone has their own limit, but very often I cannot tell. I am kind of blind. Also, I have no goal, no purpose. I know the direction but I don’t know exactly the path. I have to figure that out. So that’s the meaning.

WWD: Are you doing more architectural work?

A.W.: No, I am just doing one more for my own. I have settled in Portugal. To convince myself that is my new home, I thought that maybe I would build something. Otherwise, what’s my relation to anywhere? I have started to build a building of old structure with no nails. It’s almost like a secret how it is parceled together. No nails.

[Showing a video of the expansive raw construction site on his smartphone] That’s the condition it’s in now. It’s pretty large. It’s really large. It functions as the largest single example of this kind of construction in the world. I have to create a big problem and then I solve it. That gives me a sense of a game.

WWD: Is it 300,000 square feet?

A.W.: Exactly, how did you know that? [Showing an aerial shot of the property] That’s above the roof. There will be an open courtyard [in the center].

WWD: That will be magnificent.

A.W.: It’s pretty interesting anyway.

WWD: Will you use it for public purposes as well?

A.W.: It’s useless. It’s a private place. I don’t need a building. I told you I created it because I have to create something, like a game.

WWD: Are there a few illustrators, artists, photographers or filmmakers that you are particularly intrigued by right now?

A.W.: Not so much [in terms of] connections in the art world. I don’t go to museums or gallery shows.

WWD: Are there any just through social media or online?

A.W.: I do it only when I have time. Social media is the best thing to help you kill time.

WWD: What are you most proud of so far?

A.W.: Proud of? I wake up and think, “Oh, I should be proud that I’m still alive. Going through so much, and I am still alive.” So, my heart. I am proud of my heart, while it is secretly still pumping for 66 years. I don’t even notice that it’s working. I am very proud of that.

Best of WWD