The Apple advert that brainwashed America

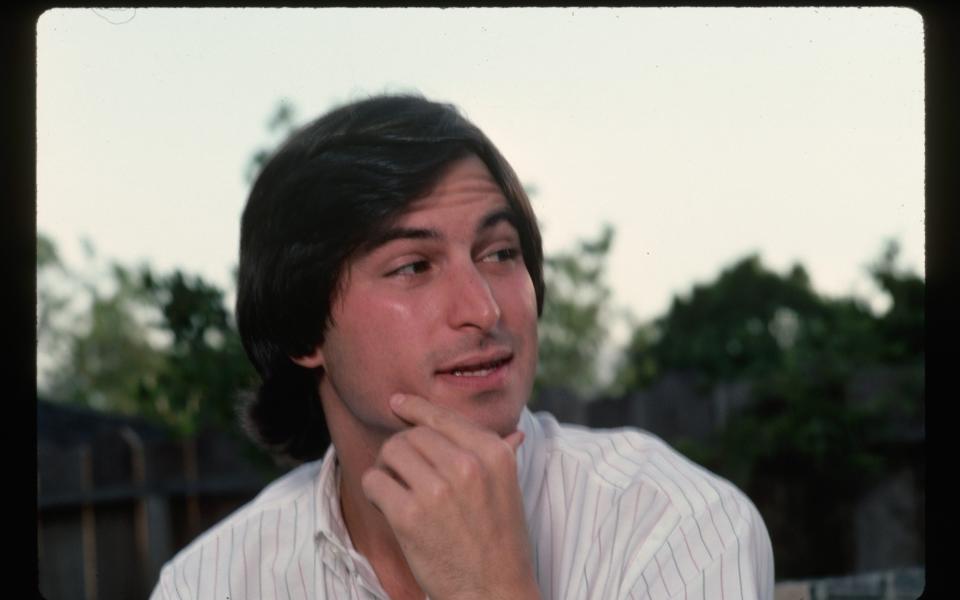

Ridley Scott was confused. In 1983, he was asked to direct an advertisement for a new Apple computer to be launched the following year. He imagined Apple had something to do with the Beatles. Chiat/Day, Apple’s then public relations firm, assured the British movie director this was a different Apple. “They said ‘no, no, no. Apple is this guy called Steve Jobs’” recalls Scott. “I went, ‘Who the f--- is Steve Jobs?’”

Significantly Scott was celebrated as the director of two bravura dystopian movies Alien (1979) and Blade Runner (1982), as well as the creative force behind advertisements for Hovis and Chanel no 5.

No wonder Apple wanted the South Shields-born director to sprinkle some of his magic dust on their new computer. They wanted him to help share the fantasy of the Apple Mac as a game-changing, liberating, must-have piece of kit for the home or office.

Scott read the script for the Apple ad with growing mystification. The setting, he realised, riffed on the storyline of George Orwell’s novel Nineteen Eighty-Four. But something was missing – there was no mention of the product. “My God [I thought]. They’re not saying what [the Mac] is, they’re not showing what it is,” Scott told the Hollywood Reporter. “They’re not even saying what it does. It was advertising as an art form. It was devastatingly effective.”

Scott is being modest. It was in no small measure down to his bravura realisation of the script that was broadcast on US TV as a 60-second commercial at halftime of the 1984 Super Bowl that the ad was devastatingly effective.

In the finished film, glum, grey workers sit in a vast grey hall before a huge screen. Scott astutely hired these extras from Britain’s skinhead community – they certainly give off the aura of a downtrodden rabble whom no sensible person would invite round for cucumber sandwiches.

As they sit, Big Brother declaims from the screen:

“Today, we celebrate the first glorious anniversary of the Information Purification Directives. We have created, for the first time in all history, a garden of pure ideology – where each worker may bloom, secure from the pests purveying contradictory truths. Our Unification of Thoughts is more powerful a weapon than any fleet or army on earth. We are one people, with one will, one resolve, one cause. Our enemies shall talk themselves to death, and we will bury them with their own confusion. We shall prevail!”

Yawn! What communist gibberish! Thank heavens that there is a noise at the back of the hall. A sexy young woman in orange shorts and white singlet is running towards the screen, eluding Big Brother’s pursuing lackeys in their futuristic helmets. The young woman was played by Anya Major, a model and discus-throwing athlete, who the following year would appear as the eponymous heroine in the video for Elton John’s Nikita.

Major got the part following a casting call in London’s Hyde Park in which several of the women auditioning for the role struggled to control their sledgehammers. One unsuccessful candidate nearly hit a passer by when she released too early. By contrast, Major was a master of torque, increasing angular acceleration as she rotated before releasing the sledgehammer at the right moment to optimise both velocity and distance. Not many models can do that. She got the part.

In the completed ad, she swings her sledgehammer then releases it into the screen, ending Big Brother’s broadcast, and preparing millions of TV viewers in the USA for the final triumphant message.

“On January 24,” the voiceover told viewers. “Apple Computer will introduce the Macintosh. And you’ll see why 1984 won’t be like [Orwell’s] Nineteen Eighty-Four.’” Across America. millions of TV screens went momentarily blank before they were filled with an image of the today-ubiquitous Apple logo.

The message? Apple Mac would liberate downtrodden masses from the totalitarian surveillance state. All viewers needed to do to secure such liberation was pay US$2,495 (£1,960.16) which in today’s money amounts to about $7,000 (£5,500). Apple CEO Steve Sculley insisted that the Macintosh be priced $500 higher than Apple’s co-founder Steve Jobs wanted, to include the cost of advertising and publicity, not least Scott’s iconic ad.

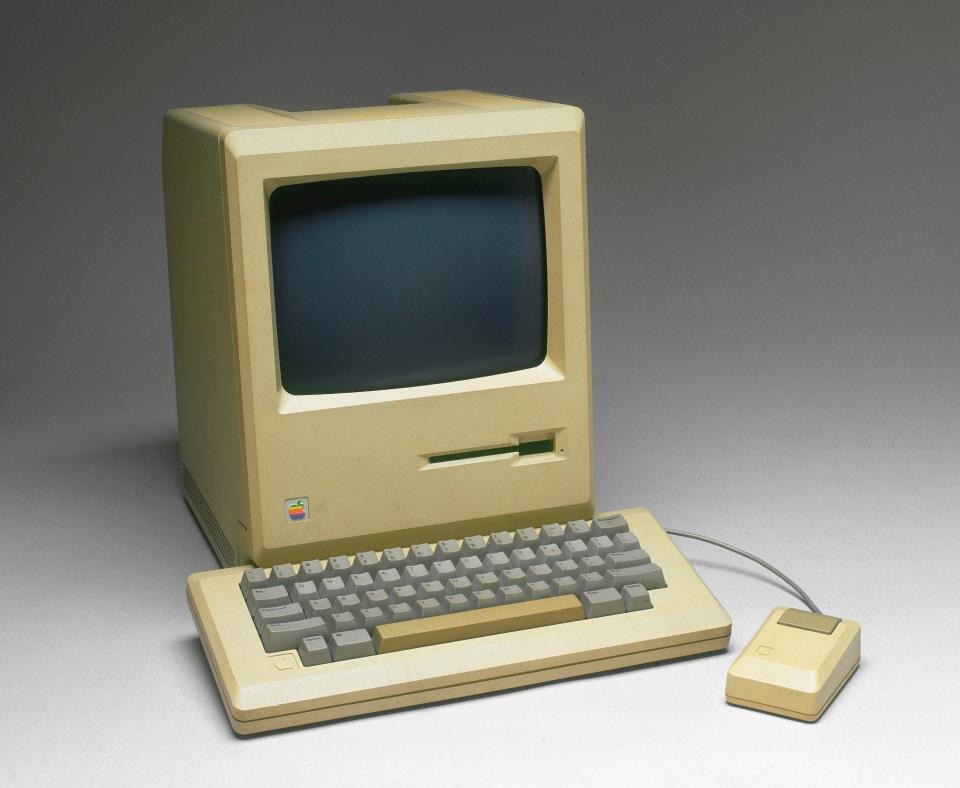

Even though the ad was iconic and the product revolutionary, the Apple Mac proved a flop. “It was a dazzling but woefully slow and underpowered computer, and no amount of hoopla could mask that,” wrote Jobs’s biographer Walter Isaacson. It had a small, monochrome monitor, blocky graphics, a feeble 128K of memory and no internal hard drive. It quickly became nicknamed the “beige toaster” by detractors . While 70,000 Apple Macs were sold by April 1984, by the end of that year it was selling only 10,000 a month and Apple was plunged into a crisis that ended when Jobs was ousted from the company he co-founded.

That, of course, wasn’t the end of Steve Jobs’s story. In 1997 he staged a boardroom coup and became Apple’s chief executive. The second coming of Steve Jobs yielded the products with which he is now associated, namely the iPod (launched in 1997) and iPhone (2007). Indeed, the 1997 Apple TV ads used historical figures such as Gandhi and Einstein, suggesting that they, like Jobs, were liberating figures because in the campaign’s solecistic description they “Think different”. Jobs was, so the campaign suggested, the latest in the line of liberating heroes freeing humans from shackles be they real or mental. Jobs’ gadgets were sold as liberating devices.

Four decades on from Ridley Scott’s Apple Mac ad, its message of human liberation seems, in hindsight, risible. We do not live in the utopia promised by the Super Bowl ad, nor in the liberating world the Think Different campaign foretold, but in a conformist dystopia more nightmarish than those of Ridley Scott ‘s best movies.

True, the fall of the Berlin Wall five years after the Apple Mac was launched did herald the end of rule by the real-life Big Brothers of the Soviet bloc, but in our current world of digital surveillance and data mining, in which your every key stroke exists in the cloud, you’d be forgiven for thinking that we live in something if not quite as totalitarian as Orwell’s dystopian nightmare, then something similar. We are ruled not by Big Brother but tech bros such as Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg, Jeff Bezos, and current Apple CEO Tim Cook.

But here’s the twist. Big Brother needed electroshock, sleep deprivation, solitary confinement, drugs, rats in cages and hectoring propaganda broadcasts to keep power, while his Ministry of Plenty ensured shortages of consumer goods so that subjects were in an artificial state of need. Today’s tech giants have more effective tactics to ensure we do their bidding. They have ingeniously made us desire our own domination, glutting us with must-have goods. So, at least, argues Korean German philosopher Byung-Chul Han in his book Psychopolitics, in which he distinguishes between 20th century totalitarian control and its 21st century successor.

“Confession obtained by force has been replaced by voluntary disclosure,” Han argues. “Smartphones have been substituted for torture chambers.” Well, not quite. Torture chambers still exist. But the point remains: control of the masses beyond the wildest imaginings of real-life wannabe Big Brothers including Hitler, Mao, and Stalin has been achieved largely by more subtle means.

As for Ridley Scott, he continues a lucrative association with Apple. His production company, Scott Free, signed a first-look deal with Apple TV+ in 2020 and his Napoleon film was made for the company.

That said, Scott clearly does have misgivings about the cultural impact of Apple. “Advertising is changing dramatically,” Scott recently told The Hollywood Reporter. “And the problem is it went onto this,” says Scott, holding up his iPhone, “which was both genius and the enemy.”

Scott’s concern is that advertising now breaks into what people are trying to read, that it becomes a disruptive distraction — and a very short one at that,

“It’s now in segments, where you’re trying to find an article and there’s 19 little snippets of it,” he says. “Is it effective? I very much doubt it.”

It’s a good point, no doubt, but the more significant one is that the great octogenarian director recognises the truth about Apple. It is both genius and, if you’re serious about liberation from technological control, the enemy.