How the blood-soaked killers of Imperial Japan nearly escaped justice

In March 1943, on the island of New Guinea, a young Australian pilot was put on a truck by his Japanese captors. It was twilight, and the young man gazed out wistfully at the hills and sea, lost in thought. When the truck eventually came to a halt, he was ordered down and told he was about to be killed. He knelt on the ground, and a few minutes later, he was beheaded by sword. Hissing could be heard as blood spurted from the neck. “The head,” noted a Japanese diarist, “is dead white, like a doll.” A senior corporal laughed: “Well, he will enter Nirvana now.”

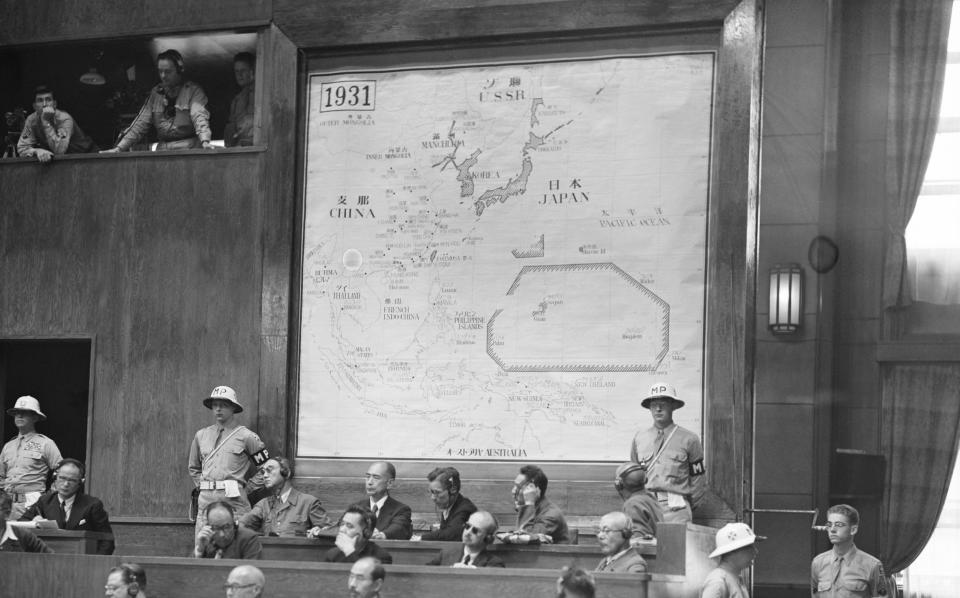

This was one of the many disturbing testimonies heard at the courtroom on a hill overlooking Tokyo, where, between 1946 and 1948, 28 of Japan’s war leaders were put on trial. The list of rapes, bayonetings, beheadings, cannibalism and extreme torture appalled those listening. In the Anglophone sphere, the Ichigaya trial has been remembered far less well than that of the Nazi leadership at Nuremberg; yet in Judgement at Tokyo, the American scholar Gary J Bass proves their significance every bit as forensically as the best courtroom lawyer.

The trial itself was a mass of paradoxes and conflicted interests, and beset by significant debate over the justification of its authority and rulings. It was held in a city and a country laid waste by US bombers. Near the start of the trial, the Philippines became independent; halfway through, India followed, then Burma. China, already devastated, became embroiled in a catastrophic civil war that would see many more millions killed and displaced. By the time the process in Tokyo ended, American and Commonwealth judges were sitting alongside a Soviet colleague, even as the Berlin Airlift was underway.

Judgement at Tokyo, subtitled “World War II on Trial and the Making of Modern Asia”, is thus not just a book about the trial itself, but also the nature of the Allied victory and Japanese defeat, and the emerging world in the Indo-Pacific. In a theme to which Bass repeatedly returns, racism and anti-imperialism were major features of both the trial and the climate in which it was prepared and concluded. The Japanese insisted their war was one of liberation from white colonials – “Asia for Asiatics” – yet, in their war of conquest, they repeatedly showed themselves capable of far greater cruelty and supremacist attitudes than any Western colonial power had. Bass’s examination of India, British rule, the tragedy of the Bengal famine, and particularly his analysis of the Indian nationalist leader Subhas Chandra Bose – still venerated in India despite siding with the Nazis and Imperial Japan – are fascinating and creditably even-handed, at a time when balanced views are often lacking.

At the heart of the trial lay a problem: how to pin local war-crimes on Japan’s leadership. With China gripped by civil war and the Japanese having torched many of their papers, the Chinese struggled to amass hard written evidence for the horrific deeds performed on their soil. Even more problematic was agreeing the trial’s authority and justification, in the absence of a programme as clear-cut as the Holocaust. The trial president, Sir William Webb of Australia, privately believed that waging aggressive war was not criminal – in opposition to the prime argument of the prosecution. In the end, all living and sane defendants were found guilty of at least one count; yet four of the 11 judges dissented, including, most outspokenly, Radhabinod Pal, a Bengali lawyer and academic and apparent loyal servant of the Raj. Pal remains a hero in Japan to this day.

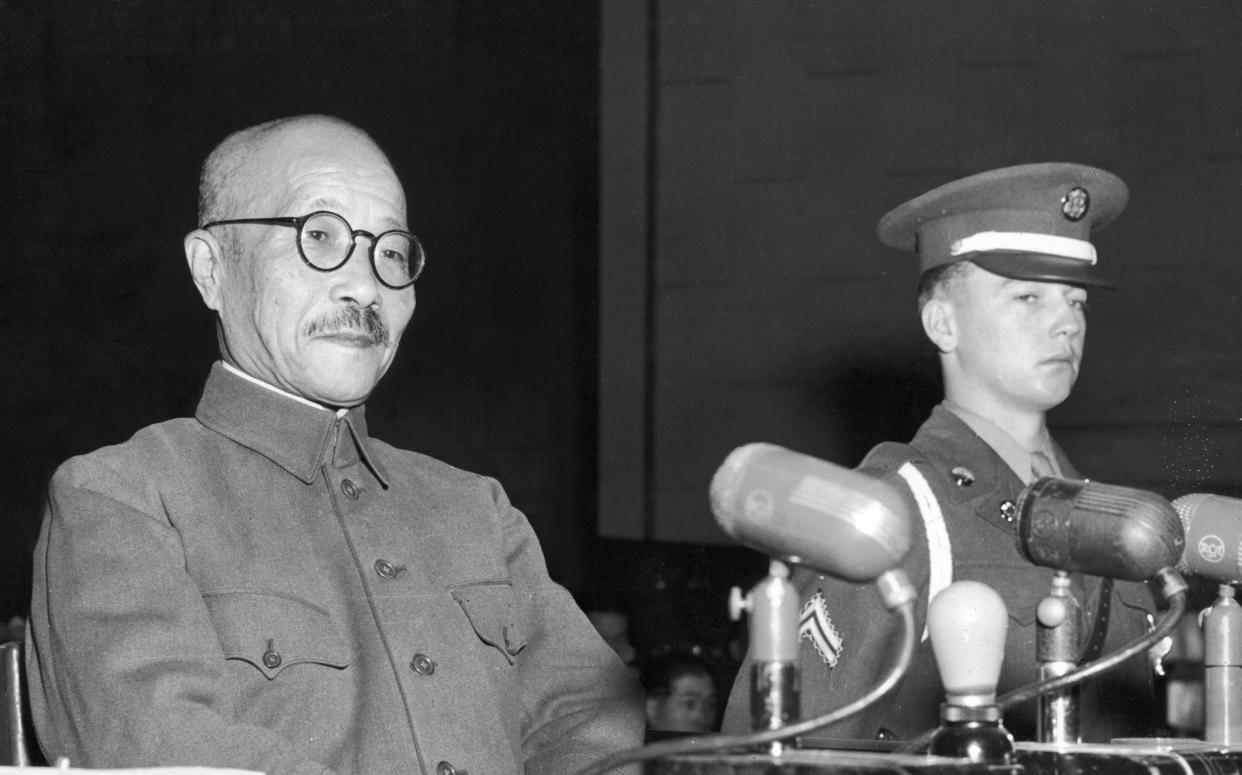

The American-led victors strived to bring legal justice rather than nationwide retribution, in order to help build a lasting global peace – ideals that already lay in tatters in India, China and elsewhere around the Far East. In contrast, Japan itself emerged from the war as a peaceful, democratic and astonishingly successful nation state. Part of this success was the insistence of the Americans, and particularly General Douglas MacArthur, that Emperor Hirohito remain in power, despite his all-too-obvious culpability. This was another of the trial’s paradoxes: realpolitik trumped the ultimate perpetrator’s guilt. Seven men in all, meanwhile, were hanged, including Hideki Tojo, the ultra-nationalist hawk and wartime prime minister, and one of the towering figures in Bass’s book.

Every so often, a new work emerges of such immense scholarship and weight that it really does add a significant difference to our understanding of the Second World War and its consequences. Judgement in Tokyo is one such, a monumental work in both scale and detail, beautifully constructed and written, leaving the reader not only moved but disturbed as well. And Bass’s book is published at a time when Europe is once again at war, with the number of casualties and depths of destruction rapidly reaching 1940s levels – unthinkable a few years ago – while, overseas, the Middle East is in turmoil, many parts of Africa are in conflict and sabres are rattling again in the Pacific. Political leaders and military commanders around the world should read this book – and, with a bit of good sense, hurriedly learn the cautionary lessons it holds.

Judgement at Tokyo by Gary J Bass is published by Picador at £30. To order your copy for £25, call 0844 871 1514 or visit Telegraph Books