In Bologna, Maurizio Cattelan Has the Last Word

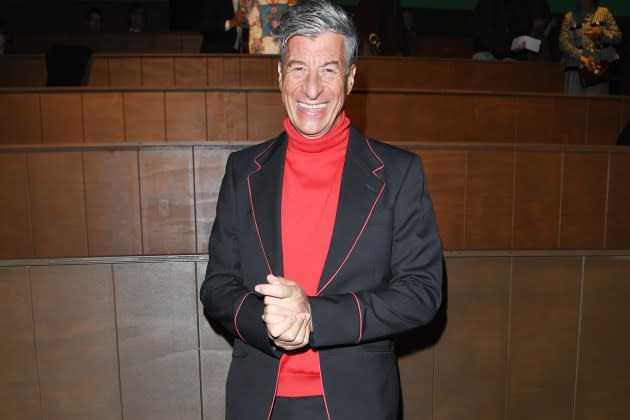

MILAN — Maurizio Cattelan has never worked with tiles but Thursday his latest landmark installation made with luxury ceramics maker Mutina and its Mutina for Art curator Sarah Cosulich kicked off Bologna’s Arte Fiera trade show.

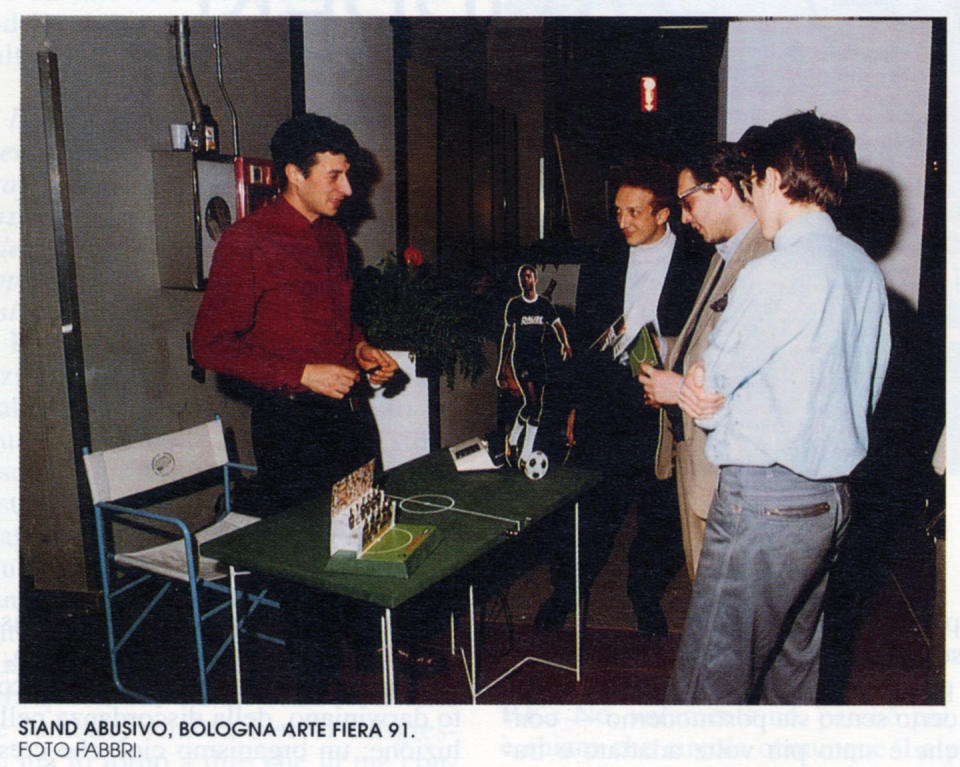

This wouldn’t be the first time his art was disrupted or he disrupted society with art. In 1991, as a young aspiring artist, Cattelan decided to showcase his work at Arte Fiera without having registered, been officially admitted or obtaining the proper permits. Bottom line — he didn’t get caught.

More from WWD

This month, and as it celebrates 50 years, the fair organizers have invited him back, on an official, legal basis this time.

Named “Because,” the showcase was constructed using the Fringe tiles designed for Mutina by Michael Anastassiades and is situated in the fair’s special exhibition space. A “guilty” cat sits beside a painting of a short circuit in the form of a “Z” shape, ready to flee, explained Mutina — much like Cattelan when he infiltrated the fair 33 years ago.

WWD chatted with the artist famous for monumental pieces, like the marble middle finger in front of Milan’s Stock Exchange.

WWD: What gave you the idea for your rogue stand back in 1991?

Maurizio Cattelan: In that period I was testing the best way to start speaking the language of art. It was a work in several acts. At that time, I hadn’t yet moved to Milan. I was living in Forlì and gravitated towards Bologna. Having a football team is, today as then, a status symbol, not only in Italy. Those were the years of [former AC Milan soccer player Ruud] Gullit and [late Italian Prime Minister Silvio] Berlusconi but also of the migrant ships who were looking for a better future in Italy, and of the Northern League. All this first resulted in a football team made up of migrant players from what we would now call the Global South. The team was called A.C. Forniture Sud, sponsored by a mysterious Russian company. I went to promote the team with an illegal stand at Arte Fiera that year.

WWD: Tell us a little about the story? How did they discover you? Did you get caught?

M.C.: No, everyone assumed I was working there for real. Every morning, I would set up the table, the chair and, to appear more professional, a telephone, and showed the pop-up leaflet with the team photo and the coat of arms. I didn’t get caught.

WWD: I have read you have held a lot of jobs (reportedly an accountant, a cleaner, a mailman and, finally, a nurse). When was the first time you felt someone in the art world took you seriously?

M.C.: Probably when I sold the first piece, or when a curator invited me to be part of an exhibition in a museum. I don’t recall when it was exactly, but it must have been around the beginning of the ’90s.

WWD: Did your parents struggle with your lack of direction in the beginning? When did they realize that you had an acumen and talent for art as a child?

M.C.: They didn’t at all, at least when I was a child. Together with my sisters, we were moving targets, blaming each other to avoid the punishment. The first memory I have from school was a suspension in first grade. I don’t remember why, but the teacher wrote in the notebook that I shouldn’t show up the next day. My parents should have signed the note from the teacher, and I spent a whole day imitating [forging] my parents’ signature so as not to face their judgment and punishment. They never found out. Also, the report card never arrived at my parents because I kept forging their signature. When I first saw Truffaut’s “The 400 Blows” (1959) I thought they had made a movie about my life. It was a revelation. For the first time, I realized that not all in my life until that moment was to be trashed and forgotten: it could become the live material to work with.

WWD: What was your stand about and what did it stand for?

M.C.: There’s only one photo, and it’s more than enough! The afterword is that I would have liked the team to play, but in the museum where I was invited there wasn’t the space to improvise a football field, so I thought of using the same team on a table-football table made specifically for 11 players. Incredibly, I found a manufacturer, Garlando, willing to make a change to their product, as long as he first did a test in the company with his employees. It was I think the closest thing to a performance I’ve ever done.

WWD: I saw the invite for” Because” — a skeleton. Why? Can you give us a preview of what it will be and the idea behind it?

M.C.: This collaboration with Mutina is the opportunity to work again with Sarah Cosulich, who curates the Mutina for Art project. Sarah asked me to present two of my works from the collection of Mutina’s founder Massimo Orsini within the fair. It is not a booth, it is not a showroom, it is not an art gallery, but it is also all these things. It seemed right to keep the promise I had made in the city: “I’ll be right back.” The skeleton is an image I took in America: it’s something every herd-keeper has in their house, to keep the bad luck away. In a such battered economy everybody should have a skeleton in the closet, as a talisman.

WWD: What was your experience working with ceramics? How did this collab with Mutina come about?

M.C.: I didn’t exactly work with ceramics, but on ceramics, as you’ll see. I have an open relationship with this material: the last time I worked with ceramics recently was to get the mold of the Guggenheim water closet to make it into solid gold. This time Mutina offered me a ceramic stage.

WWD: If your art was a tool, what would it be used for? What would its power be?

M.C.: I have a soft spot for vacuum cleaners. They are the closest thing to magic. I wish my work could be the same.

*

Mutina for Art is a project linking ceramics specialist Mutina to the exclusive world of contemporary art through special projects. Also curated by Cosulish and on display until March 27 at Casa Mutina Milano is “100 Days” by Peter Dreher, the German artist famous for painting the same empty glass for 45 years. During Milan Design Week, Mutina kicked off festivities with a project coproduced by Nilufar Depot, envisaged by Spanish architect and designer Patricia Urquiola for Mutina, a structure made of a 3D element known as Jali.

Best of WWD