What your bookshelves say about you

Good news for print publishers: The Notting Hill Bookshop, which was made famous by Richard Curtis’s 1999 film, has reported that paperback sales have doubled in the past couple of years. Interestingly, considering the widespread speculation that technology would kill off the traditional means of reading, we’ve got tech to thank: it’s social media that is inspiring Generation Z to pick up real books, via TikTok’s #BookTok hashtag, and Instagram’s #bookstagram and #booknook.

This is also good news for those of us who take pleasure in dissecting other people’s bookshelves and are glad to be reassured of continued opportunity (RIP CD collections) to find points of common interest, make discoveries – and judge.

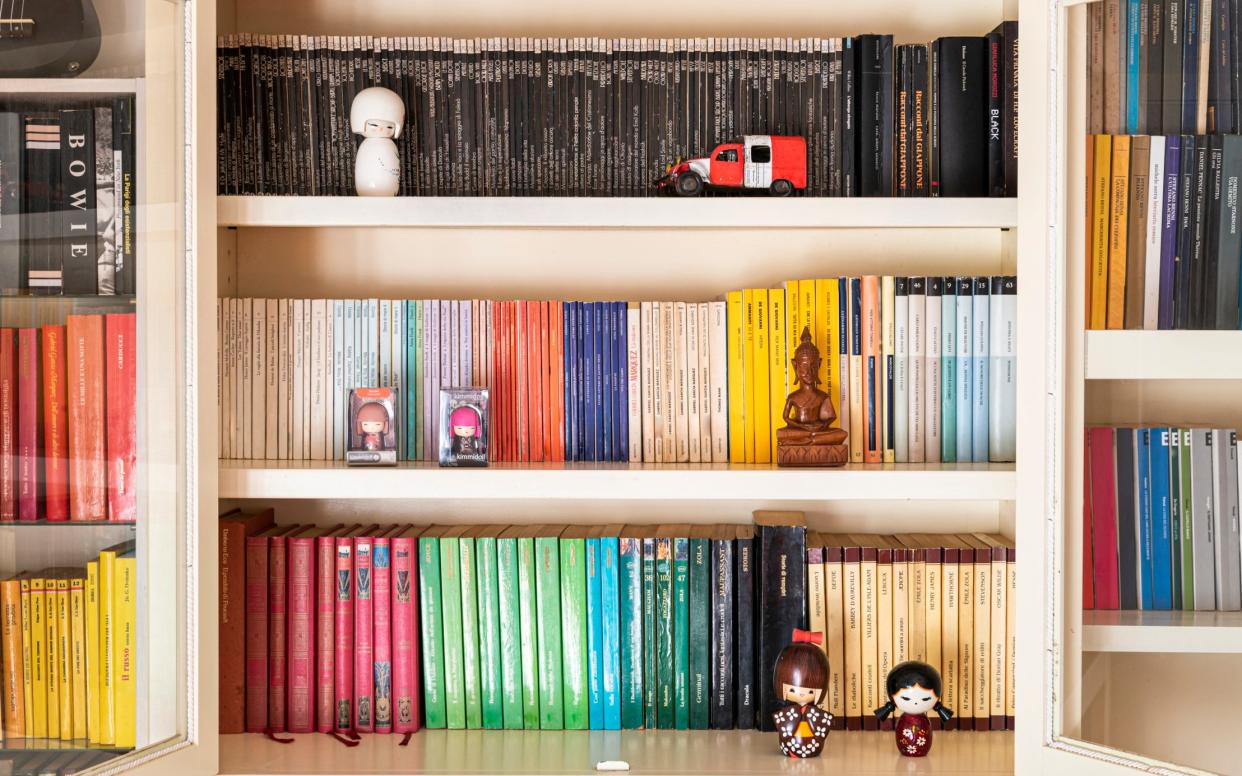

Books have been recognised as cultural capital since the Paris salons of the 17th century popularised their purchase, but beyond the curiosity of “what book”, there’s the “how” – and “it’s not much of a stretch to say that the way we display books says a lot about our personalities,” observes Brandon Schubert, an interior designer. Upping the ante is the fact that, although home libraries do exist – the renowned Heywood Hill bookshop in Mayfair has a “libraries department” – most of us lack a dedicated room and are instead endeavouring to combine system with aesthetics.

I, for instance, have distributed books throughout my house according to type, with fiction in custom-built shelves on the first-floor landing arranged by alphabetical order of author; Sylvia Plath separated from Barbara Pym by Marcel Proust. I am efficient, perhaps unimaginative, and few would describe me as free and easy – guests seldom stay longer than two days.

Schubert, on the other hand, “puts books on shelves without any thought to organisation”: romance next to reference books next to science fiction, “except that I try to vary heights and widths so that the end result is inconsistent, and I always incorporate vases, glass ornaments, sculptures – all sorts of things”. It’s an approach that marks him out as a creative and collector who is probably better at spontaneity than me (I happen to know that he joins in family games).

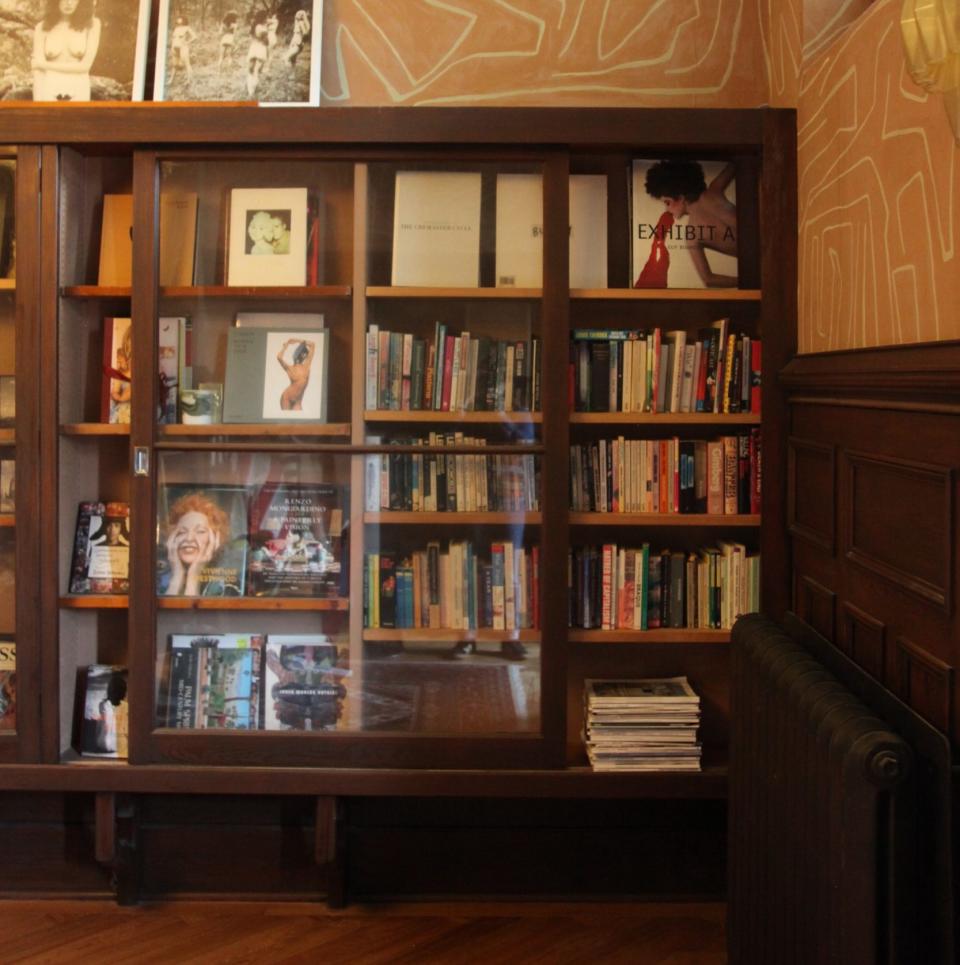

It’s possible, of course, to arrange shelves in such a way to imply insouciance. “I think it looks very relaxed and chic to hang a picture in front of books, as my colleague Emma Burns has done in her barn,” says interior designer Philip Hooper, of Sibyl Colefax & John Fowler. He also places large books horizontally and sometimes props a small painting on top of them – though all his spines “kiss the edge of the shelf and are vertical: it’s not on to have them slouching at jaunty angles”.

But his order is not absolute, so things can get lost, which Hooper professes to enjoy. “I like the feeling of looking for something in particular, but in searching that out you stumble on a lost treasure,” he says. There’s a compelling argument for it: the writer and publisher Susan Hill, who, in pursuit of a particular book encountered dozens that she’d forgotten about, never read, or wanted to re-read, turned the experience into a charming biography of her library, entitled Howards End is on the Landing.

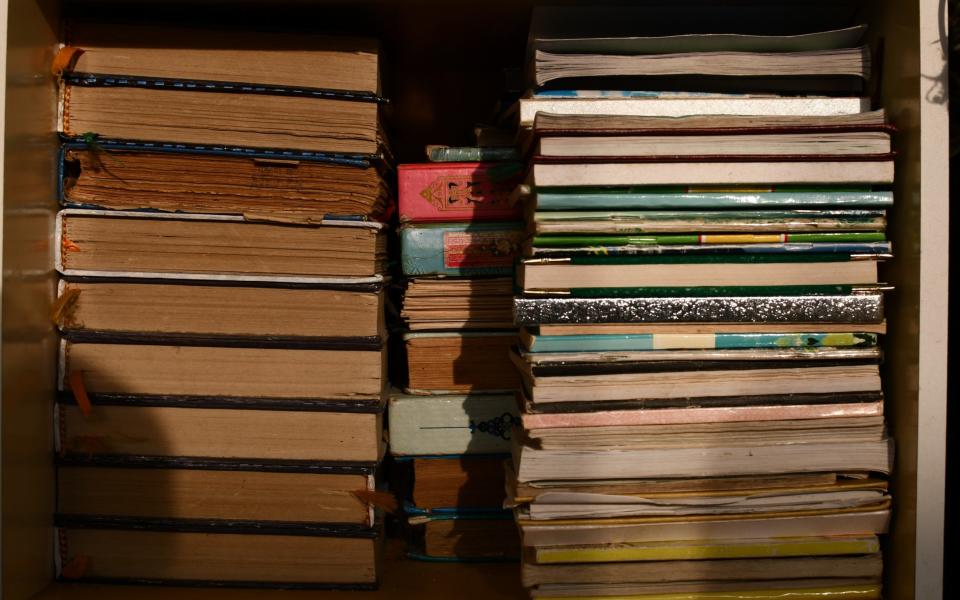

Disorder can go further: Sarah Gwonyoma of hit Instagram account @whatsarahreadnext and the online What We Read Next book club (i.e. she’s one of the bookfluencers, though she prefers the term “book critic”) confesses to untidy stacks around her bed and either side of the fireplace, which she puts down to “real life taking precedence over putting them away”.

As well as being high achieving, Gwonyoma is excellent at seizing the moment, but her system is genuinely organic. This is in contrast to the growing trend to amass higgledy-piggledy piles – which somehow still look suspiciously posed – in empty fireplaces and under windows, raising questions relating to how you find a particular title, as well as concern for the books if the window is left open and it rains.

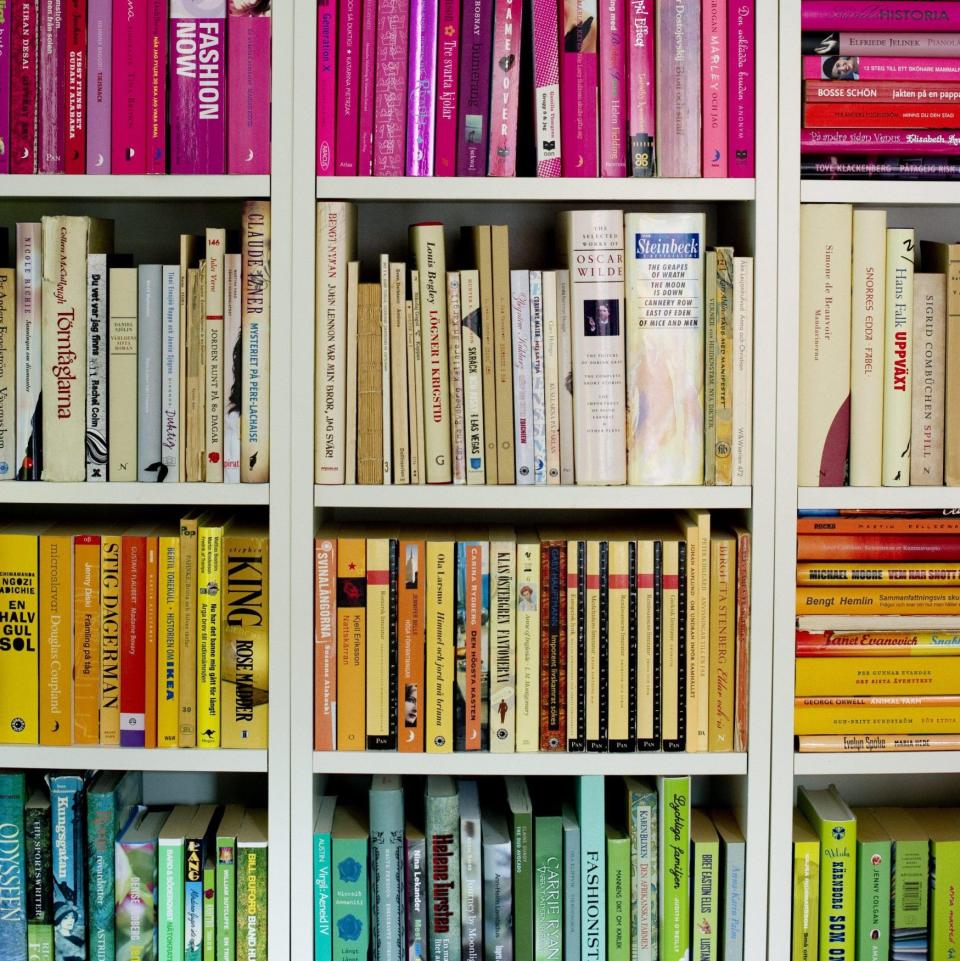

It’s a look that is seemingly overtaking grouping by colour. Tanya Willock and Temidra Willock-Morsch, owners of the New York-based design shop Hidden Gem, once compared grouping by colour to “a work of art”, but in some quarters it’s now losing favour – and fast.

“It seems a bit of nonsense and implies you never look at the actual books,” says Hooper. In fairness, Willock and Willock-Morsch did qualify their statement by saying the implementation was ideal for those with “tons of books you don’t really use” – and Hooper concedes that occasionally blocks of colour can occur if, like him, you “always keep matching spines together”.

Schubert is more tolerant of calculated arrangements – “It’s like anything else in interior decoration: folks are making a decision about how their books look best, and going for it” – saving his judgment for what is arguably more important: the books themselves.

There is nothing worse, he moots, than “a bookcase full of books that clearly do not belong to the occupants of the house, whether they’re in different languages or on topics that no one who lives there is interested in, like 19th-century bird identification in Patagonia.” Usually, he reckons, such assemblages have been acquired by the metre, to fulfil the idea that Books Do Furnish a Room – a title Anthony Powell gave one of his novels (a marketing masterstroke if ever there was one).

But what of those who read, and yet prefer visually restrained surrounds? Architect William Smalley – who, as a student, “had a side gig arranging books for the smart customers of Heywood Hill” – has “big built-in cupboards which are lined with shelves like a mini-library; there is also a bar. All my books are hidden away, and I’m glad not to have them shouting at me”.

Such desired minimalism is often the argument given for storing books with the spines facing in, a practice which simultaneously offers a potentially pleasing arrangement of texture, and consistently meets with widespread derision. Many suspect it as a means of disguising a diet of contemporary thrillers by those who claim their literary allegiance lies with James Joyce and other difficult modernists. “Spines facing inwards is clearly stupid,” retorts Smalley.

Disingenuousness of display is a nuanced matter, for we may claim that our collections are autobiographical, but some of us make cuts – and slightly incredulity-stretching submissions. I have not so much glanced at a page of the aforementioned volumes of Proust (though intend to, one day, and my copies were my grandparents’, who, incidentally, catalogued their books using their own variation of the Dewey Decimal system).

But they’re on a shelf, unlike the well-thumbed torridly gothic works of Virginia Andrews, which are hidden (let’s say from my children). Similarly, says Hooper, “I’m not sure I want the world to see my collection of vintage Just William books.”

The interior designer Scarlett Gowing’s approach is more honest, for she intends that the bookshelves guests will see are specifically representative of a moment in time – the moment being now. She performs regular edits, moving books she keeps for sentimental reasons into other rooms, and will show off the cover of a new art or design book by placing it front forward, “so friends will notice it, and can enjoy its beauty, and we’ll talk about it,” she explains.

And thus her enthusiastic desire for engagement coincides with Gwonyama’s posting of a book on Instagram – from which we can conclude there’s more than one way of running a literary salon, just as there’s more than one way of curating a shelf.