Built 104 years ago, historic Black Charlotte school begins its new life Saturday

More than a century after the Siloam School opened for Black students living in the Mallard Creek community, it’s beginning anew teaching history.

A group of citizens sought to save the one-room schoolhouse, and with the help of the Charlotte Museum of History, raised enough money by November 2022 to restore it.

With renovations finished, the museum is holding a grand reopening on Saturday, beginning at 11 a.m. Entry will be free, and the reopening will feature a ribbon-cutting ceremony and a chance to tour the school. The school can be found on the museum’s campus, at 3500 Shamrock Drive.

Attendees will be able to see the school’s new windows, doors, fresh paint, among other renovations. The museum will also provide tours.

With the museum’s effort to help the restoration, the project exceeded its fundraising goal, raising $1.2 million. The community’s commitment spurred larger organizations to contribute major dollars to get the project over the finish line, Terri White, the Charlotte Museum of History Director, said.

She also said the school’s restoration signifies a new direction and broader view of Charlotte’s history for the museum.

History and restoration process

The Siloam School was among thousands of structures designed by Rosenwald-era school plans, which created “state-of-the-art” schools for Black students in the Jim Crow era. However, the school was not built under the Rosenwald fund, which built schools and colleges for Black students in the South before desegregation

Local craftsmen and tradesmen built Siloam School, which is on the National Register of Historic Places.

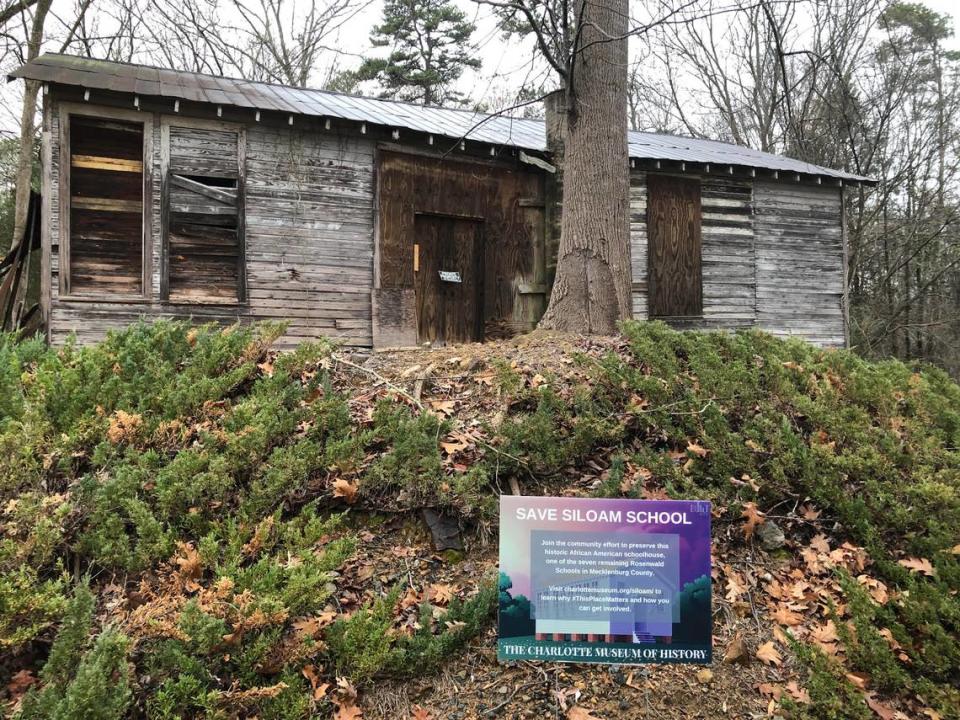

The building functioned as a schoolhouse until the 1940s, when it was bought by a family who used the structure first as a home, and later an auto garage. Over time, the building became endangered due to disrepair. There were boarded-up windows, rusted containers and cobwebs covering the corners of floors and ceilings.

By the 1980s, the structure was no longer used by the family, and the property was purchased by a developer in the early 2000s.

In 2016, the Save the Siloam School project took off. The museum, along with community members, created a plan to relocate the school from the Mallard Creek area. Crews moved the building in 2023 to the museum’s campus in east Charlotte to restore it as a community resource and education center.

White said the building’s origin story speaks to the spirit of the Charlotte community today.

“You have a community of people that are like, ‘Oh, you mean our ancestors worked hard to get this done? And they did it all on their own despite all odds? Well, (yes) we’re gonna save it despite all the odds,’” she said.

People from all kinds of professions and walks of life contributed to the restoration. They included historians, of course, but there also were glassblowers, painters and carpenters involved.

Siloam School and the Museum’s future

For decades, the Charlotte Museum of History has featured exhibits about colonial Charlotte and Revolutionary statesman Hezekiah Alexander, White said. The Siloam School’s renovation is part of the institution’s transformation to a modern history museum which focuses on interpreting local stories.

Former Charlotte Observer columnist and editor Fannie Flono served as the project’s chair. She said the project held community engagement sessions early on to learn what the community wanted.

Many Charlotte residents, including Flono, have relatives who attended Rosenwald schools in the South.

“And so that’s of interest to people, about how those Rosenwald schools were set up and the specific design on them.” Flono said. “Those buildings were set up so well, and a lot of them still exist. A lot of them have obviously been torn down.”

What’s next for Siloam School?

Terri said the museum is working to specialize Siloam School field trips to facilitate conversations about how Charlotte’s local history has changed over time. The museum is also finalizing a Siloam educator institute, which will provide training and tool kits for educators.

“We know that the themes of segregation and racism and Jim Crow are difficult for some people to talk about,” she said. “So we’re hoping that through artifacts, the school itself, oral history, tangible, factual things, that we can help teachers better prepare on how they’re going to have those conversations with their students either in the classroom or before they come on campus.”

For the community to address inequities, it’s important to understand their origin, Flono said.

Flono said she’s happy that the project is nearly complete. Every day the Siloam School sat on Mallard Creek Church Road, she thought it could be torn down or vandalized.

“Anything could have happened to that building while I was out there,” Flono said. “And so to know that five years later, it is actually saved and restored and available for people to get a grasp on the history behind it is just a remarkable thing.”