Burberry’s profits are set to tumble – a ‘best of British’ strategy is trying to turn them around

When Kate Moss turned 50 earlier this week, there were the inevitable reminiscences about her most iconic fashion moments. While the Croydon-born supermodel has been the face of Chanel, Saint Laurent and Calvin Klein over the years, there is one label with which she is particularly aligned: Burberry, the revered British heritage brand whose campaigns she fronted 18 times in 20 years (1998 - 2018).

While Kate greeted her milestone birthday in the peak of health, alas, the same cannot be said for Burberry. Last week, the 168 year-old company announced that due to sluggish trading in the run-up to Christmas, it was lowering its profit forecasts to between £410 million and £460 million, down from earlier predictions of as much as £668 million. The results saw stock fall by as much as 15 per cent in London, the sharpest decline in more than a decade, making Burberry one of the worst performers of London’s biggest companies. Shares lost almost a third of their value last year.

If this is worrying news for British fashion, it’s particularly worrying for the 700 workers employed by Burberry’s factory in Castleford, Yorkshire, where its trench coats are made, and its mill in Keighley, Yorkshire, where its gaberdine is woven.

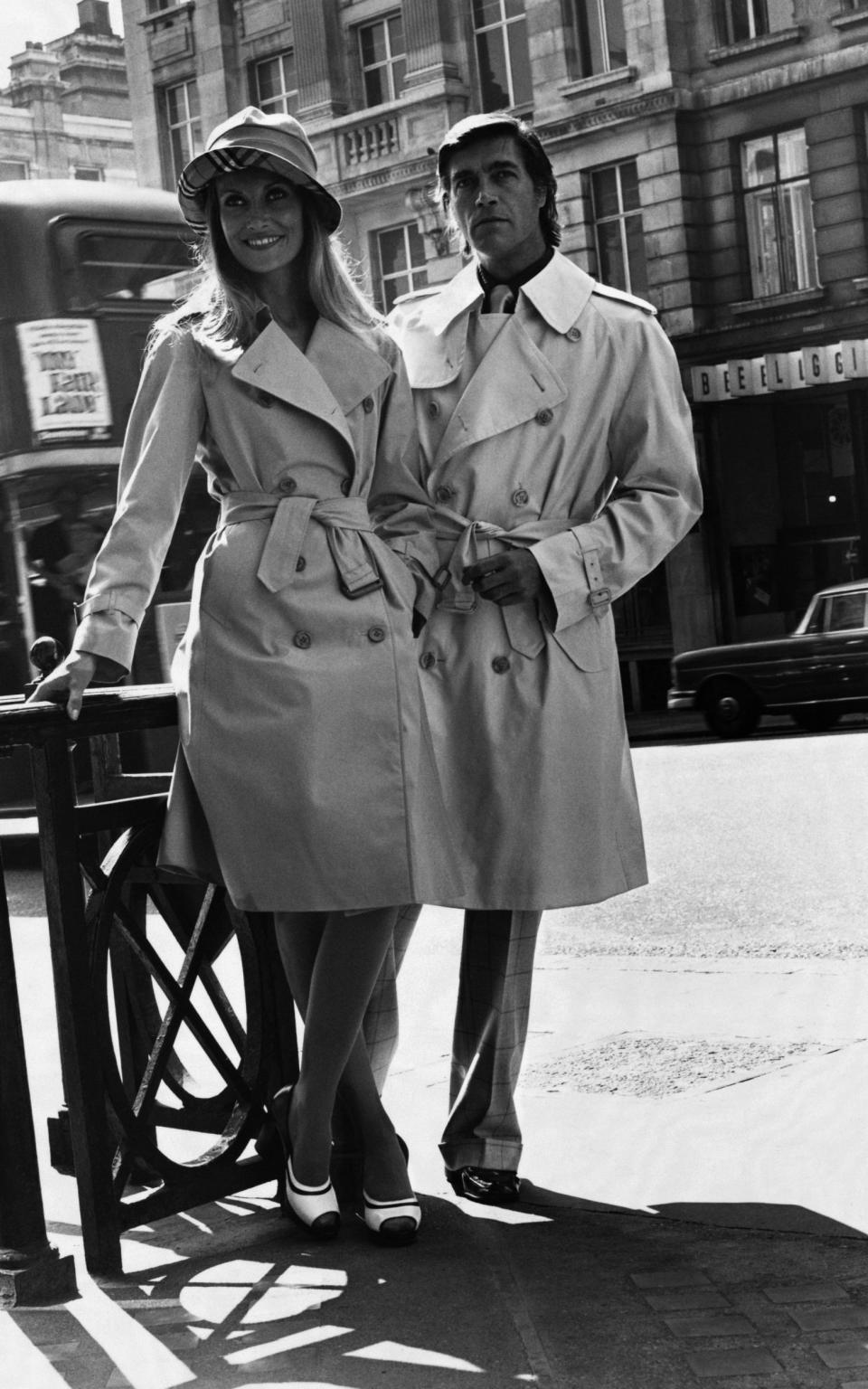

First introduced by Thomas Burberry after he invented the waterproof fabric in 1879, Burberry’s trench coats are the heart and soul of the brand. Sir Ernest Shackleton wore an early version on three notable expeditions; serving officers wore them throughout the First and Second World Wars. If there was an Oscar for coats, Burberry’s trenches would be a shoo-in: notable celluloid appearances include Meryl Streep in Kramer vs Kramer (1979) and Michael Douglas in Wall Street (1987).

Burberry’s Britishness has always been its key selling point. Often cited as one of the late Queen Elizabeth’s favourite brands (and also a favourite of Queen Camilla), Burberry is as British as tea and cake, holder of two Royal warrants, the most bona fide luxury heritage brand this country has produced.

It may not boast the sales of Louis Vuitton, but Burberry’s classic house check is as globally recognised as the ‘LV’ monogram of its French rival, and worn by a slew of all-ages fans including David Beckham, Sienna Miller, Ryan Gosling, Gwyneth Paltrow, Jacob Elordi, Helen Mirren, Adele, and the Prince and Princess of Wales.

Which begs the question: what has gone wrong? The answer is not straightforward. In the luxury sector, trading conditions are more challenging than ever, and Burberry is far from the only brand to be flailing. “Burberry isn’t getting anything massively wrong – the state of the economy across the world is the biggest factor at play here,” says Fflur Roberts, head of luxury goods at Euromonitor. “It doesn’t matter which industry you’re in – consumers are squeezed, and disposable income is down.”

Certainly, shoppers worldwide have been shying away from the eye-wateringly higher price points being introduced by most luxury brands, proving that inflation is hitting the one per cent as well as the rest of us. Burberry is particularly reliant on Chinese shoppers, who have been slow to return to Europe. Like its rivals, it has also been affected by the government’s decision to scrap VAT-free shopping for tourists, with the result that they find it cheaper to make their purchases in other European countries than the UK.

In addition to these challenges, Burberry could also be said to be suffering from an identity crisis – albeit not one as critical as that of 2004, when a pub chain banned Burberry-wearing youths from drinking in its establishments, and the storied house check found itself being worn by celebrities so downmarket as to damage its exclusive image.

In March 2018, Burberry’s longstanding creative director, Christopher Bailey, exited the business after 17 years “to make way for a new chapter in the brand’s creative strategy”, as it was explained at the time. Yorkshire-born Bailey’s collections drew heavily on references to Princess Margaret and the Mitfords, peddling a luxurious version of English eccentricity that played well to foreign buyers.

It wasn’t cutting edge, but it sold well. When Bailey was replaced by Riccardo Tisci, formerly of Givenchy, Burberry’s ‘cool’ factor increased, abetted by his high profile, international celebrity friendships (Madonna, the Kardashians) and his knack for creating viral moments on social media.

But many felt that his Italian roots didn’t convincingly transplant to a brand that was so famed for its Britishness. When Tisci exited in 2022, he was replaced by Daniel Lee, another Yorkshireman who seems perfectly placed to steer Burberry through choppy waters. Lee is cool, but not in a nebulous way: as well as being Phoebe Philo’s right hand man during her successful tenure at Celine, he turbo-charged sales at the sluggish Italian leatherware brand Bottega Veneta, where he was creative director from 2018-2021, winning a clutch of awards for his efforts.

Most pertinently, Lee has a midas touch with handbags, the cash cows of every luxury brand and an essential driver of image and sales. Unusually for a £3 billion brand, Burberry has never been a go-to for bags. At best, you’d describe theirs as practical and well-made. At worst, you’d describe them as instantly forgettable. As the designer behind Bottega Veneta’s exponentially successful Cassette bag, a coveted design worn by every celebrity worth her multi-million social media following, Burberry is quietly counting on Lee to deliver another hit.

There’s no doubting Lee’s keen commercial instincts, or his understanding of the power one killer accessory can have in shifting the dial. In the digital age, the right handbag, shoe or pair of sunglasses can change a brand’s fortunes overnight.

When Lee unveiled his first Burberry collection in February 2023 (watched on by guests including Vanessa Redgrave, Bianca Jagger, Jodie Comer and Baz Luhrmann), some found his bold cobalt blue reworking of the classic house check a little too radical for comfort. Maybe, but does anyone care about the clothes?

It’s a genuine question, and one that luxury brands need to consider. Fashion may no longer be driven by a colour, skirt length or aesthetic mood (“Nancy Mitford picking roses in her cottage garden” doesn’t really cut it these days), but nor is it enough to plough all your efforts into creating a covetable handbag, however obsessed with single ‘objects’ younger customers may be.

Burberry has a long and venerable heritage. It stands for craftsmanship, and it’s a positive sign that Lee, like Bailey, feels a responsibility to preserve its Britishness. In 2019, Burberry scrapped plans for a new factory in Leeds, part of a £50 million investment that pledged to create 200 additional jobs, denying the decision had anything to do with Brexit, though its impact surely played its part.

But Burberry does appear to give back, stepping up during the pandemic and utilising its global supply chain to deliver 100,000 surgical masks to the NHS, as well as repurposing its factory in Castleford to make non-surgical gowns and masks.

If karma fuelled sales, Burberry would be thriving. In terms of its digital strategy, it should be thriving, too. Burberry has always been ahead of the game, live streaming its shows years before many of its contemporaries – and last season, it created a viral moment when it took over the north London café Norman’s, inviting Mary (Bur)Berry in for a cup of tea and a photo session, a stunt which arguably garnered more ‘likes’ than any of the Hollywood celebrities who graced the front row at the actual show.

For all the money that Burberry has spent over the years on lavish fashion shows, and glossy ad campaigns featuring supermodels, A-listers and a 12 year-old Romeo Beckham (its current campaign draws on a slew of famous faces from stage, screen, music and sport including Rachel Weisz, Neneh Cherry, Bukayo Saka and Damon Albarn), its current situation is a stark reminder that if the product itself isn’t desirable, all the marketing in the world won’t shift it in sufficient numbers.

Which is scant consolation to smaller or fledgling brands, an increasing number of whom can barely afford to stage a fashion show. If Burberry, with its slick marketing, deep pockets and genuinely talented creative director is struggling to thrive, what hope is there for everyone else? Nobody wants the global fashion industry to turn into an oligopoly, where only the biggest, wealthiest players can survive. Alas, in today’s challenging conditions, it takes a lot more than “best of British” to prosper.