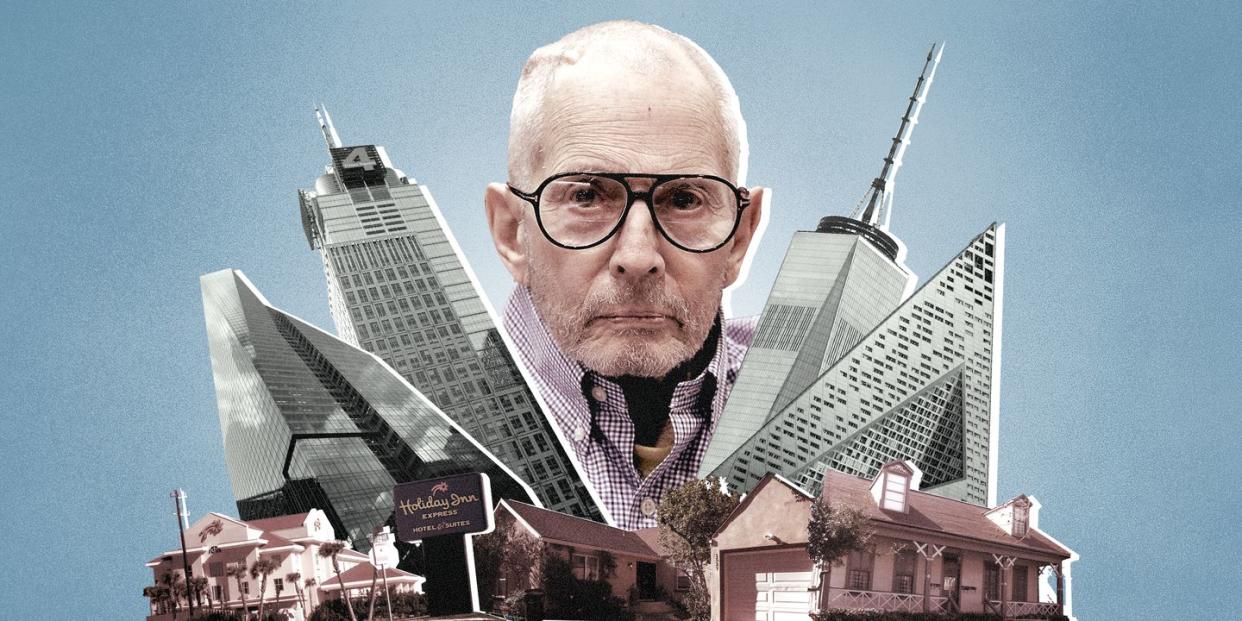

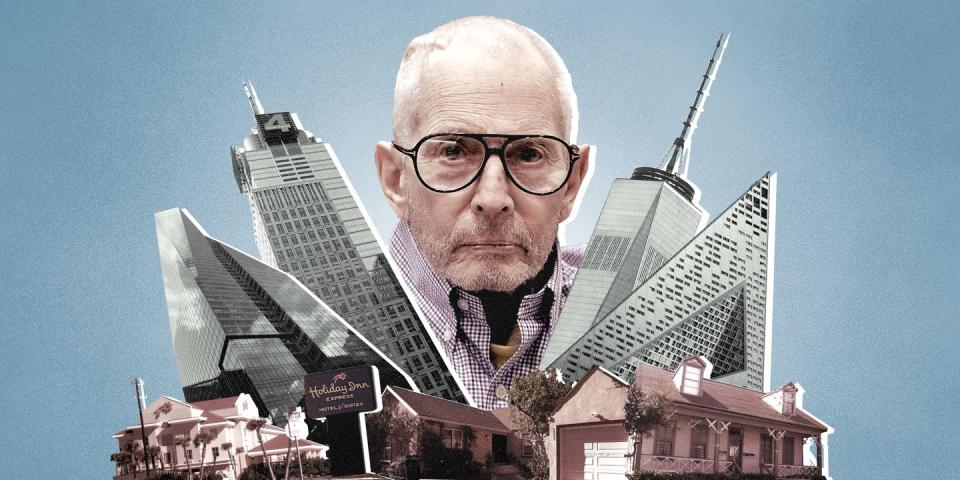

You Can't Choose Your Family: Can the Dursts Survive Robert's Murder Trial?

Update: Closing arguments in the murder trial of real-estate scion Robert Durst began this week in Los Angeles County’s Superior Court, after being delayed due to the coronavirus pandemic for more than a year. Durst is accused of murdering his friend Susan Berman in 2000, and early arguments in the case were heard in March 2020 before the trial was halted.

In November 2015 hundreds of well-wishers crowded into the lobby of the 52-story tower at 4 Times Square, the skyscraper credited with kicking off the neighborhood’s resurgence, to honor the people who built it. It was the 100th anniversary of the Durst Organization, and the family members behind the company—which has made them New York real estate royalty—were celebrating inside one of their most famous buildings.

Wait staff circulated with cocktails, and the lobby’s brightly lit limestone walls were lined that evening with images of Joseph Durst and his son Seymour, who, with his brothers, became master developers, amassing a fortune estimated at $5.2 billion.

Guests marveled at the models of the family’s 11 skyscrapers jutting into the Manhattan skyline and at photographs of a string of striking residential buildings, such as the pyramidal Via 57 West, which overlooks the Hudson River. Among the participants were members of the fourth generation of Dursts to work at the family firm: Helena, Alexander, and Lucas. “We created an enduring family business, which supports tens of thousands of people and is responsible for changing the skyline,” Douglas Durst, the family’s current patriarch, told me that day. “With each generation, the business grows.”

There was, however, one omission among all the memorabilia on display: an image of Robert A. Durst, Seymour’s eldest son and the family’s black sheep, who has been dogged by suspicions of murder for nearly four decades.

This week, Robert is scheduled to go on trial in Los Angeles for killing Susan Berman with a gunshot to the back of the head in Los Angeles nearly 20 years ago. The prosecution argues that Robert killed her because he feared she was about to betray him to the authorities, who had reopened the investigation into the 1982 disappearance of his first wife, Kathie McCormack Durst.

Robert, now 76 and sitting in the Los Angeles County Jail, has been estranged from his family for a quarter century. He is practically a taboo subject among the Dursts, one of his nephews tells me. Family friends, who follow Robert’s comings and goings, say they are loath to bring him up in his family’s presence for fear of alienating his normally stoic relations.

In addition to the HBO documentary The Jinx: The Life and Deaths of Robert Durst, which brought his case to an international audience and won an Emmy, Robert has been the subject of a lightly fictionalized movie, a couple of television specials, and numerous books. He casts a shadow on the family’s reputation, and his upcoming trial for the murder of Berman is only the latest chapter in his long, strange story.

This family saga is about to enter its next act: a high-profile trial that will explore not only every nook and cranny of Robert’s life but also delve into his privileged upbringing and his family’s position in New York society.

The Black Sheep

The upper echelon of New York’s real estate world has had its share of rivalries and scandals (although they usually play out behind closed doors, lest they damage business or reputations). Remember Abe Hirschfeld, the real estate tycoon, self-proclaimed inventor of the open-air garage, and owner of the New York Post? In 2000 he was convicted of trying to hire a hit man to kill his business partner and served two years in prison. Afterward he ran unsuccessfully for the U.S. Senate.

But Robert Durst’s story, spanning three deaths, three states, and nearly four decades, is in a category of its own. It also raises the question: How does a family like the Dursts handle such a public airing of its dirty laundry?

So far, people who would know say it hasn’t affected the business, which involves 13 million square feet of Manhattan office space packed with blue chip tenants, apartments all across New York City, and projects in development in Dutchess County, New York, and Philadelphia. The Dursts are also still welcomed in philanthropic circles, where they’re known for supporting environmental organizations (like the Trust for Public Land) and the performing arts.

Still, some social observers think the family will pay a price for Robert’s public troubles. The family of Kathie McCormack, his first wife, filed a $100 million lawsuit against not only Robert Durst but against, among others, his current wife, Debrah Charatan; Douglas Durst and Wendy Durst Kreeger, as co-executors of the estate of Seymour Durst; the estate of Susan Berman; and Michael S. Struk, the detective (now retired) who first investigated Kathie’s disappearance, in 1982. The suit alleged a wide-ranging conspiracy to keep hidden the death and disappearance of Kathie Durst, but sources have confirmed that it was dismissed yesterday.

“They are a low-key family,” says the society publicist R. Couri Hay. “But they can’t escape the raised eyebrows. I’m sure this is the last thing they want to talk about to anyone at an outing or charity event, but they will suffer for the alleged crimes of the brother.”

And that’s just what the family’s patriarch wants to avoid. “While I think that Douglas manages the issue well,” says Jonathan Durst, Robert’s cousin and the president of the Durst Organization, “I hate to see what it does to him.”

At the time of the 100th anniversary, Forbes ranked the Dursts at No. 59 on its list of the richest families in America. Even then the Dursts could not escape Robert’s shadow. Nearly half the Forbes text describing the family was about Robert’s legal troubles.

“You can’t choose your relatives, but you can choose your friends,” says Jeff Gural, a rival developer whose family owns a sizable stake in the Flatiron Building, among other New York attractions. “I think everybody is sympathetic, [but] I do think they’re happy he’s locked up.”

The trial will no doubt generate another round of unwanted scrutiny for his family. “The Durst family has been one of the champions of New York City’s growth,” says Mitchell L. Moss, professor of urban planning and policy at New York University. “Seymour Durst was a genius at understanding that you could never fail if you built near a subway. His children and grandchildren have built on that tradition. Robert, the alleged killer, is a striking departure.”

The American Dream

The Dursts emigrated to the United States from Eastern Europe more than a century ago. According to family lore, Joseph Durst landed on the Lower East Side in 1902, from Gorlice, Austria, with $3 sewn into his lapel.

He went from being a tailor’s apprentice to selling children’s clothing from a pushcart, eventually opening a garment factory with a partner. When his partner bought him out in 1915, Joseph used the proceeds to buy his first property, 1 W. 34th Street. He also got into banking, forming Capital National Bank, to make loans in the city’s bustling garment district. When the bank was sold, he used the profits to focus on real estate, buying and selling existing buildings.

Joseph’s sons Seymour, Roy, and David got into the business in the 1940s and pushed into development. Seymour was a skilled negotiator, with a talent for assembling small parcels into major development sites, first along Third Avenue and later in the Times Square area.

Robert Durst grew up in Scarsdale, New York, outside Manhattan. As a child he was profoundly affected by the death of his mother in 1950, when she fell off the roof of the family house in a possible suicide. “I just remember [Robert] as a very difficult child,” says his cousin Nan Rothschild. “He was the only one who was really difficult when we had family gatherings.”

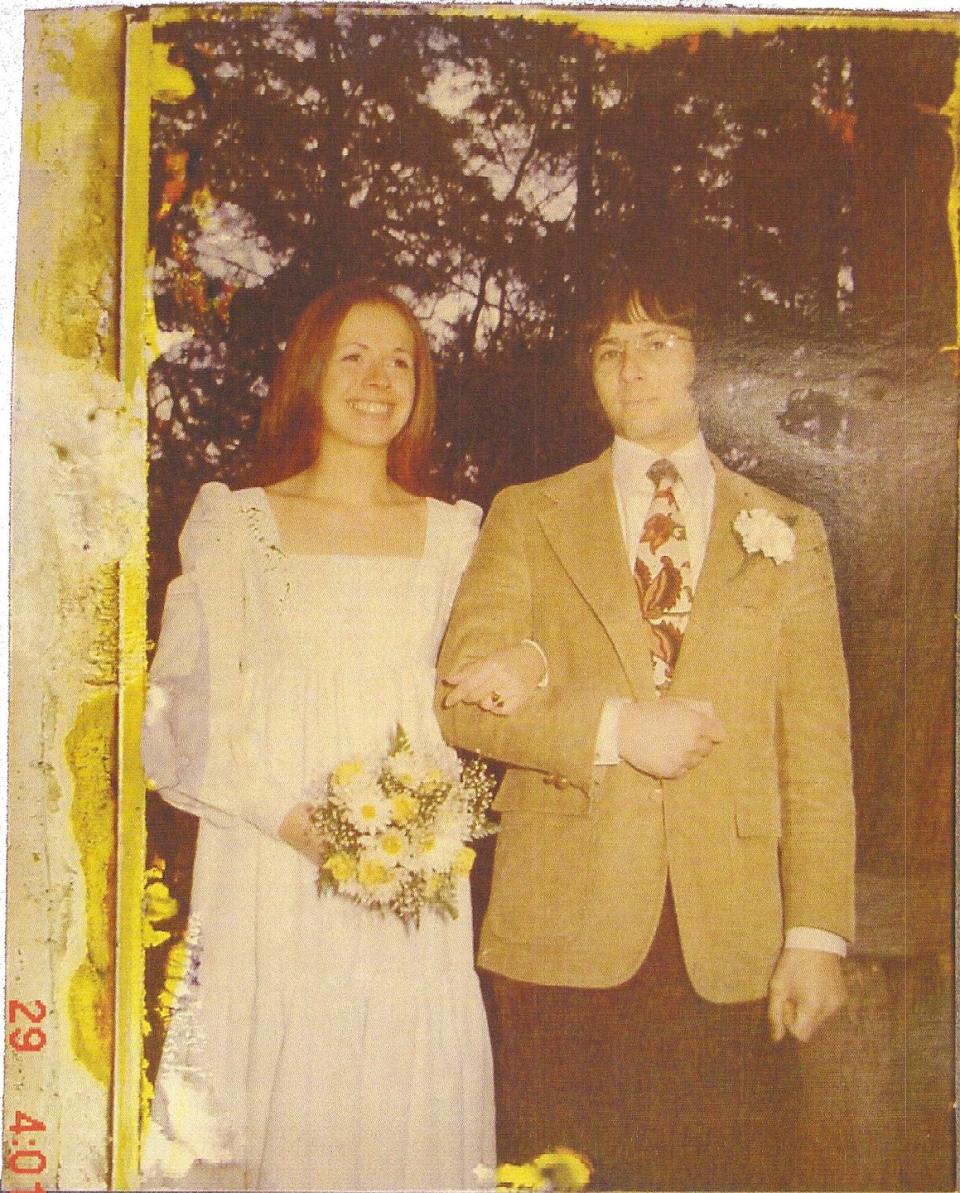

Still, Robert graduated from Scarsdale High School, earned a degree in economics from Lehigh University, and attended graduate school in Los Angeles—though he never earned a doctorate, as he used to claim. In 1973, Robert joined the family business and was given the responsibility for collecting rents and, sometimes, negotiating leases. The same year, he married Kathie McCormack.

By the late 1970s, Robert’s marriage to Kathie was unraveling. When she vanished, in 1982, only months before she was to graduate from medical school, the story hit the front pages of the tabloids—and Susan Berman helped manage the media. Robert told the police and reporters that his wife might have run away with a drug dealer. However, investigators and Kathie’s friends and family long suspected Robert, who they said had become increasingly violent with his wife. Her sister Mary told me that as soon as Robert told her that Kathie was missing, she told her husband Tom Hughes, “I think he killed her.” But with little evidence and no body, the story soon faded.

Although Robert still maintains that he doesn’t know what happened to Kathie, he has conceded that much of what he told the police at the time was false. Whether he believed his son’s story or not, Seymour Durst backed Robert and never offered Kathie’s family any consolation, the McCormacks say.

“He told me on a number of occasions that Kathie was spotted in different parts of the country,” Seymour’s friend, the developer Larry Silverstein, told me in 2002. “But they were never able to get to her in time.”

The investigation went dormant and would remain that way for 18 years.

A Change of Heart

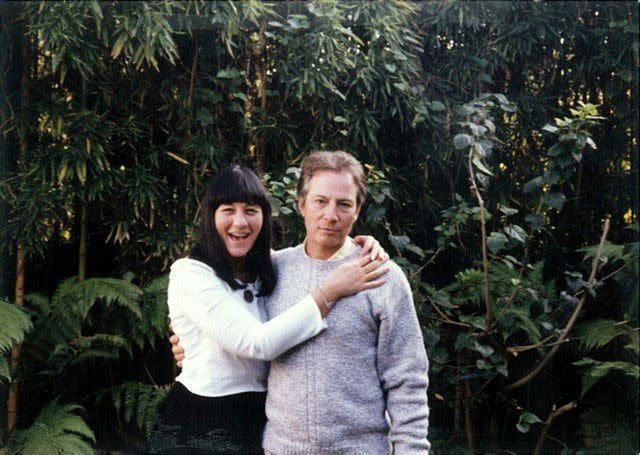

Robert returned to the fold in the mid-1980s. To outsiders he appeared to be his father’s heir apparent, and he proudly told friends of regular Sunday breakfasts à deux with his father. Robert helped manage the business and was a presence on the New York social scene; he was friendly with Studio 54 founder Steve Rubell and regularly attended ballet performances. He traveled and dated women, one of whom, Debrah Charatan, a real estate executive, would eventually become his wife.

But by the late 1980s he was becoming increasingly erratic. According to family members Robert gave Charatan rent money he collected and stacks of company vouchers for black cars, until Douglas put a stop to it. As children the two brothers had fought constantly, and Douglas still worried about what his brother might do. Robert kept a heavy plumber’s wrench on his desk, and Douglas countered by placing a length of pipe on his own.

Other family members shrugged off this kind of behavior until Robert took to using his uncle’s garbage can as a urinal. “My uncles didn’t frown on it as long as it was my wastebasket,” Douglas says. “When it was their wastebasket it became an issue.”

In 1992 the elder Dursts replaced Robert with Douglas as the successor trustee for the family trusts, and two years later they formally named Douglas heir apparent. Humiliated, Robert failed to turn up at a planned lunch and never returned to the office. He cut himself off from his friends in the real estate industry and even skipped his father’s funeral, in 1995.

“To me,” says Jonathan Durst, Robert’s cousin and the president of the Durst Organization, “it was another indication of how erratic Bob’s behavior was.”

Robert’s peripatetic existence, and the Durst family’s world in New York, was rocked in October 2000, when he learned that the authorities had reopened the investigation into his wife’s 1982 disappearance, setting off a new round of headlines.

Unbeknownst to the family, Robert was hiding out in Galveston, Texas, and New Orleans, posing as a mute woman. Investigators were eager to talk to Robert’s friend Susan Berman, who was then living in Los Angeles, but before they could, Berman was found dead. Ten months later Robert was arrested in Galveston on charges of killing his neighbor, Morris Black, cutting up the body, and dropping the pieces in Galveston Bay.

Robert was acquitted of Black’s murder despite his grisly testimony that he had cut up the body. Susan Criss, the Galveston County judge who heard the case, recently claimed she didn’t believe that Durst shot Morris Black in self-defense. Criss said, “I believe he did what he was accused of doing.”

At that time the family’s view of Robert changed dramatically. Douglas and his brother Tom feared for their lives. Their sister Wendy, who had tried to keep in touch with Robert, was devastated. In 2006, Robert settled a lawsuit against the family trusts for $65 million and severed his last ties to his relations.

From that point on, Douglas has had private investigators tracking Robert’s movements. “Up until 2001,” Douglas says, “I thought my brother was innocent.”

Opening Old Wounds

The Dursts aren’t your typical New York real estate moguls. They’re not backslappers, storytellers, or self-promoters. Douglas tends to be taciturn, with a dry humor that requires you to listen closely or risk having the joke sail past your ears. “They’ve always been a low-key family,” says Jeff Gural. “They didn’t drive around in limousines. Seymour took the subway. There was nothing fancy about their lifestyle.”

But Douglas doesn’t shy away from the occasional public spat. New York mayor Bill de Blasio, in an effort to blunt claims that he was too close to the real estate industry, cited the Dursts in a 2017 op-ed as political donors frustrated by their lack of post-election access to City Hall. The Dursts had been content to keep their disputes with the administration out of the media, but after being singled out by the mayor, a family spokesman offered an ominous retort: “Winter is coming.”

Also in 2017, Douglas Durst, an environmentalist, clashed with the billionaire Barry Diller over the latter’s plans to build a performing arts pier on the Hudson River. Durst, who once led Friends of Hudson River Park, reportedly helped finance several highly publicized lawsuits that stymied the pier project until New York governor Andrew Cuomo and the Hudson River Park Trust agreed to complete the long-stalled 4.5 mile–long park.

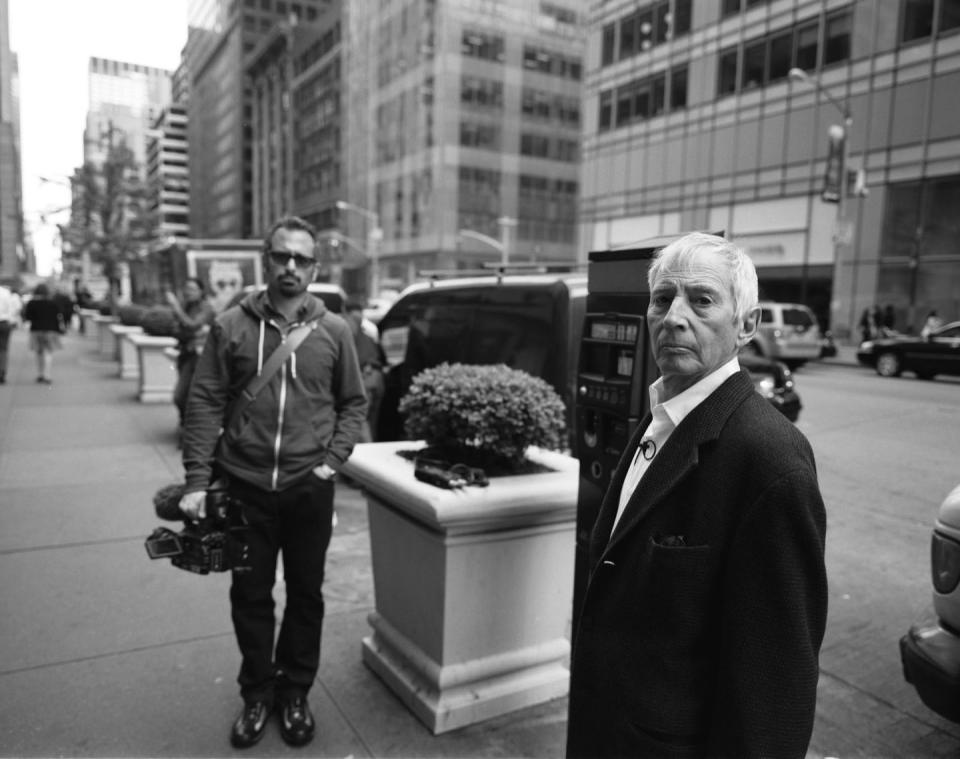

For many in New York society, Robert would have faded from memory if not for his decision in 2010 to break his silence and start talking to journalists, including two filmmakers—Andrew Jarecki and Marc Smerling—who had just completed a movie, All Good Things, based on his life.

Robert “liked the movie,” he told me in November 2010, despite its implicating him in the murders of three people. The filmmakers ultimately interviewed him for more than 20 hours, footage which became the basis for HBO's The Jinx.

Robert acknowledged during the interviews that his first marriage had been wracked by his violence and that he had lied to the police in 1982, as Jarecki and Smerling turned up new evidence. The documentary propelled the Los Angeles police to reopen the investigation into Berman’s murder. As a result, Robert was arrested in March 2015.

Now, 38 years after his first wife disappeared and 17 years after he was tried for murdering a drifter in Texas, Robert is once again in a harsh public spotlight that will ignite another round of whispers about the Durst family.

Douglas, who feared that his brother wanted to kill him, has agreed to testify for the prosecution at Robert’s trial in Los Angeles. Youngest brother Tom is also cooperating with investigators. “Bob has always been a burden for me and my immediate family,” Douglas says, “but it has not impacted our relations with others or the Durst Organization’s ability to do business.” So far, at least, he’s right.

“The Dursts are one of the great real estate families of New York,” says Madelyne F. Kirch, president of a marketing firm focused on the real estate industry. “I don’t see that Robert’s troubles have had any effect on their success.”

You Might Also Like