A decade after ‘strong not skinny’, diet culture has come full circle

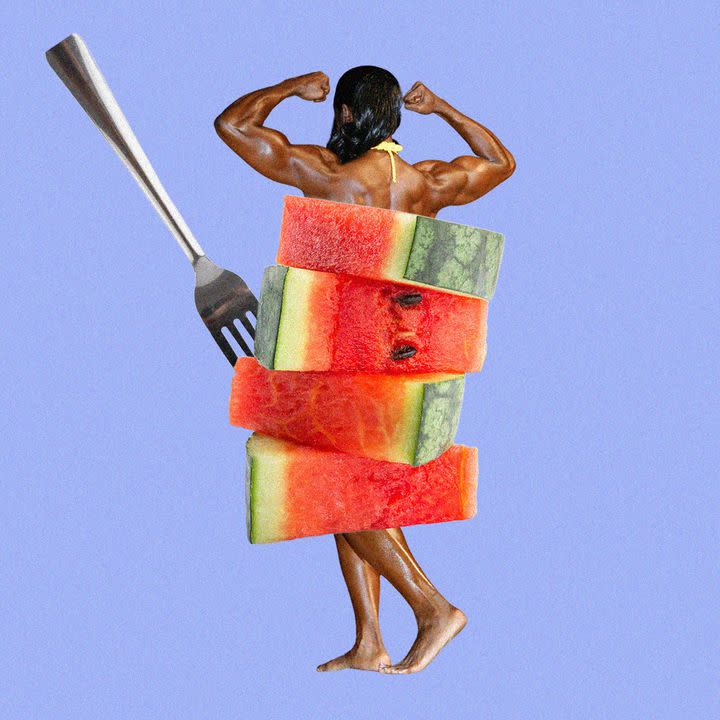

‘How to get slim, toned arms’, ‘Exercises for a snatched waist’, ‘Killer ab crack workout’ – videos with these screaming titles clog up my TikTok feed. ‘Transformations’ show already-slim bodies deplete into even smaller ones. They all extoll the virtues of weightlifting and healthy recipes. ‘What I eat in a day’ recaps are shared by influencers who, to begin their video, will pull up their top to showcase abs resembling an ice cube tray. There’s a lot of zero percent Greek yogurt and protein bars schilled with discount codes. The message is clear: eat like me to look like me.

These are all posts garnering millions of views on FitTok, today. They’re on the FYPs of 14-year-olds and Explore pages of women in their 30s respectively. Despite the apparent shift towards inclusivity and body positivity over the past decade, shaky ‘health-related’ content encouraging us to shrink ourselves and adopt worrying eating patterns is thriving, not waning. Once you might have been able to spot the #ThinSpo and #ProAna content from a mile off. But over the years, there’s a form of diet culture that has quietly – and then loudly – rebranded itself as ‘betterment’.

As a health editor and fitness trainer, I’m acutely aware of how inconclusive and lacking in nuanced research and recommendations surrounding the ‘best’ ways to move and eat that are peddled online really are. Eating styles are not one-size-fits-all. The idea that you can target specific areas for fat loss is absurd, despite what videos on ‘losing belly fat’ will have you believe.

#StrongNotSkinny’s rise

I know how harmful the resurgence of this content could be, because I’ve lived it. And I’m pinpointing one particularly modern diet culture death knell as 2014. It was a year where a new wave of fitness content filled our phone screens – people were rejecting the damaging size zero ideals of the ‘00s, and replacing it with something just as insidious: #StrongNotSkinny. The movement arose masquerading as a rejection of diet culture, but contained all of the toxic hallmarks of fat-shaming repackaged through a ‘female empowerment’ lens.

Back then, I could scroll for hours through Valencia-filtered images of women with small, round muscles posing in mirrors. My finger would incessantly tap on novelty nutrition videos that documented bowls of zoats (zucchini oats – you had to be there) and protein shakes. Then there were the closely documented six-day-a-week training plans and influencer’s bikini body PDF guides. A ‘no days off’ attitude was embedded into my brain.

I was 18 and being easily influenced by a new, shiny and appealing industry. What began with tuning into fitness content in the hopes of feeling a bit better about my body ended up with me being able to squat well over my own weight… and that’s where the positives end. The stress from following this aspirational lifestyle triggered a flare-up of debilitating IBS, my lifelong anxiety became unmanageable, and I developed amenorrhoea, a condition where your periods stop.

Since the peak of #StrongNotSkinny a decade ago, there’s been a reckoning. Many of those who led the movement are now speaking out about their hidden struggles during it. In 2017, Alice Liveing, who grew her following by sharing her chiselled body, intense workout routine and low-calorie recipes under the moniker ‘Clean Eating Alice’, ditched ‘clean’ from her Instagram handle and has since been candid about the fact that she actually had an eating disorder and exercise addiction.

Elsewhere, the founders of the popular #GirlGains community, Zanna Van Dijk, Victoria Spencer and Tally Rye, which sang the praises of strength training and macro counting, have all since shared their own unhealthy relationships with food over the years. Now, most of their content has shifted away from fat-burning and glute-sculpting workouts to body acceptance reels, with a sprinkling of ‘intuitive exercise’ (which is meant to mean listening to your body’s needs and cues rather than regimented routine) throughout.

And yet, here we are again in 2024, right where we started. Celebrities have once again shed weight en masse, detailing the allegedly ‘healthy’ diets that got them there rather than the diabetes medications they’re injecting. Online searches for ‘quick weight loss’ have increased by 581% within the past year, according to research by ASICS. Are we destined to remain in the vicious cycle of the size zero aspiration forever? Or can we stop another generation of young women from ending up in a toxic relationship with health, fitness and their own bodies?

Step-counting down a dangerous path

There’s a lot to blame for today’s return of narrowing body ideals, including the rise of social media styles that have given a new generation a route to more followers, paid-for content and an apparent algorithmic bias against people of colour and those with larger bodies. The continual digitisation of life also means that we feel pressure for entire lives to be aesthetically pleasing, from our living rooms right down to the food on our plates. New technology which has allowed us to track our health has turned our food, runs, sleep, heart rate and blood sugar levels into valuable data.

“Our health has almost become an identifier for how good or bad a citizen you really are,” Dr Rachael Kent, researcher from King's College London and host of the Digital Health Diagnosed podcast, tells Cosmopolitan. “Your sense of self-worth is tied to your health identity.”

More widely, we’ve seen a renewed focus on personal health following the pandemic. Individuals are keen to take things into their own hands, and often fall foul of misleading and unregulated content online while doing so.

Sports and eating disorder dietitian Renee McGregor has seen an increasing number of women appearing in her clinic whose exercise and eating habits have veered into dangerous territory. “It’s hard to pinpoint whether we’re seeing more people in clinic because of increased awareness [of eating disorders] or because more people are struggling, but it never fails to surprise me how prevalent restrictive eating is,” she says.

Many of McGregor’s clients suffer from amenorrhoea and other issues. “Popular tools like fasted exercise, depleting our bodies of carbs or simply not eating anywhere near enough has repercussions,” she explains. “Without enough energy, your body starts to fundamentally deteriorate internally. Bones and ligaments become weaker, your capillary systems and the production of red blood cells become modified and you become much more prone to injury and illness.”

That image: of a weak, sick, injured woman, is far from the picture of health we scroll past online, but it can be the repercussion of many of their rigid routines, restrictive eating (whether in terms of food groups or meal timings) and moving more and more… and more. Historically a side-effect associated with being a pro-level athlete, amenorrhoea is now thought to impact 26% of women who exercise, according to The Female Health Report 2023. Though the survey didn’t show that exercise was the cause of non-regular periods, the link is strong.

Of course, not all exercise or online health culture is negative. #StrongNotSkinny may not was not perfect or wholly truthful, but it helped many to find a way into movement and, after unpicking toxic narratives, a respect for their body and awe of their own strength. In many ways it did for me. Among the harms, some things were groundbreaking and positive: women were infiltrating the male-dominated weights room. They were aiming to build their bodies, not shrink them. I now see the limitations of these faux-feminist points: growth was only acceptable if it was muscle built within a tiny frame. Still, seeing a woman with a barbell in her hands for the first time in my life was still, truthfully, exciting – and spawned the career I now have as a fitness coach. Something that may never have happened otherwise.

Learning that my own period loss was likely caused by movement and diet also allowed me to suss out experts who blew my mind with research about what our bodies actually need. McGregor, Dr Emilia Thompson and Dr Stacy Sims are just a few of those who apply science rather than trends to women’s bodies. It was a gentle unravelling and realisation that the hyper-fixation on my body was at odds with the strong, feminist principles I held in other areas of my life.

Case in point: when the now infamous Protein World advertisement detailing a lean woman in a yellow bikini beside a plethora of weight loss supplements with the caption ‘Are you beach body ready?’ was plastered around tube stations in 2015, I joined the crowds lamenting how wrong it was. Then I’d open my phone and privately scroll women encouraging me to do the same. One message, articulated more insidiously. What I was absorbed by in the digital world was so removed from the person I was and wanted to be in the real world. How I treated my own body was at odds with how I believed women should be treated. And there’s only so long you can live these two separate lives.

A way forward

My recovery back to a happy and genuinely healthy equilibrium was likely smoother than it might have been if I wasn’t still slim, white and fit. For those who find the journey out of disordered eating or exercise results in living in a larger body that is continuously stigmatised, it can be much harder to separate your worth from your physical self.

That we fall into this trap is understandable: a huge part of why we, as women, have our bodies objectified, overworked and placed at risk is because they are chronically understudied. Between 2014 and 2020, only 6% of sports science research focused exclusively on women compared to 31% that included just men. It is no surprise that forcing women’s bodies into male-researched training and nutrition plans causes havoc. Or that people try to make up for the lack of science by sharing things that “worked for them”. While these are legitimate stories, a sample size of one isn’t enough to prescribe the mechanism to thousands of people.

Things are, luckily, changing. While far more must be done by social media companies to curtail the promotion of extreme lifestyles (and some progress is happening here – earlier this year TikTok was forced to introduce tighter legislation around dieting and weight loss posts), many influencers are speaking up against how diet culture has failed us in the past and we have more understanding how diverse healthy can look, rather than limiting it by BMI - a measure that is finally being scrutinised. Thinking back to the narrow bodybuilding ideal that was celebrated 10 years ago and how damaging notions of size zero and cellulite shaming were in the media in the ‘00s, we’ve come a long way.

A decade on from #StrongNotSkinny, and after my own decade online and in a career in the health industry, the only thing I know to be totally true is this: while it’s unlikely we’ll ever shake our fetishism for seeing ‘perfect’ bodies, ultimately, obsessing over your body won’t make you healthier or fitter. Impossible beauty standards are just that: impossible to achieve. But eating enough food to have the energy to do things you love and occupying the parts of your brain that once worried about your step count with more fulfilling things is far from it – and likely to bring us the happiness we falsely think we can achieve by limiting ourselves.

You Might Also Like