Equine therapy at Kansas horse farm gets vets and first responders back on their feet | Opinion

It’s not every day I’m invited to a horse farm. I’ve never ridden an equine, nor do I plan to anytime soon. But when Andy Brown of Stilwell just south of Overland Park asked me to visit the site of a foundation he helped establish for combat veterans and first responders, I accepted the invite.

Brown and Patrick Benson co-founded the nonprofit organization War Horses for Veterans in 2014 in Stilwell. Participants —- four to five at a time — come from all over the country. Local police and fire department personnel have been, too. They stay for about five days, Brown said.

Sessions include equestrian-related activities. During their stay, meals are prepared by a chef on the premises. As part of the cohort, each person has access to a mentor and psychologist on hand. The last day, the group hops on a horse for a trail ride to complete the course.

Most participants have been diagnosed with trauma-related issues such as post traumatic stress, depression and more, according to Brown. The goal of equine therapy is to help vets and first responders begin the healing journey necessary to lead productive lives.

Members of some of the nation’s top special operations forces have taken part, including U.S. Navy SEALs, U.S. Army Rangers and other elite units. An untold number of people have left Stilwell in a better mental place than when they arrived, he said.

“This place is saving lives,” Brown told me.

On my visit, I was there to tour the grounds. I met with Brown, his wife Pat Brown, former Kansas City Chiefs player Kendall Gammon, the organization’s chief development officer, and other staffers.

I was relieved Brown didn’t implore me to saddle up on one of the 26 horses on the farmland. As a guest, it would have been rude to turn him down.

Potential crisis averted.

Former Chiefs player joins nonprofit

Gammon, the former Chief, is a 1991 graduate of Kansas’ Pittsburg State University. He played football there — quite well, actually. Gammon was part of the Gorillas’ 1991 NCAA Division II national championship team. He went on to spend 14 years in the NFL as a long snapper and center. He was also a longtime sideline reporter and analyst on the Kansas City Chiefs radio broadcast network.

About five months ago, Gammon came on board as chief development officer at War Horses for Veterans, he said. In addition to his role there, Gammon is a public speaker. He uses his oratory skills to welcome new groups to the program.

He told me he finds it difficult to equate retiring from football with soldiers returning home from active duty, or the inherent dangers of working as a public safety officer. But he uses the parallel in his opening speech to military vets and front-line workers as a way to connect with them on a personal level.

“As I start out most every time I speak, which is: What the military and first responders do allows me to make something as benign as a piece of leather important in my life and I can make money from it,” Gammon said. “I’m very indebted to them.”

Fundraiser includes Frank Boal, NFL memorabilia

I was in Stillwell less than two weeks before War Horses for Veterans’ third Derby Day fundraiser on May 4. Pat Brown was busy coordinating the event. During my visit, she split time sending emails, double-checking RSVPs, VIP tent packages and other important matters. She also ordered the couple’s lunch from a local pizza parlor.

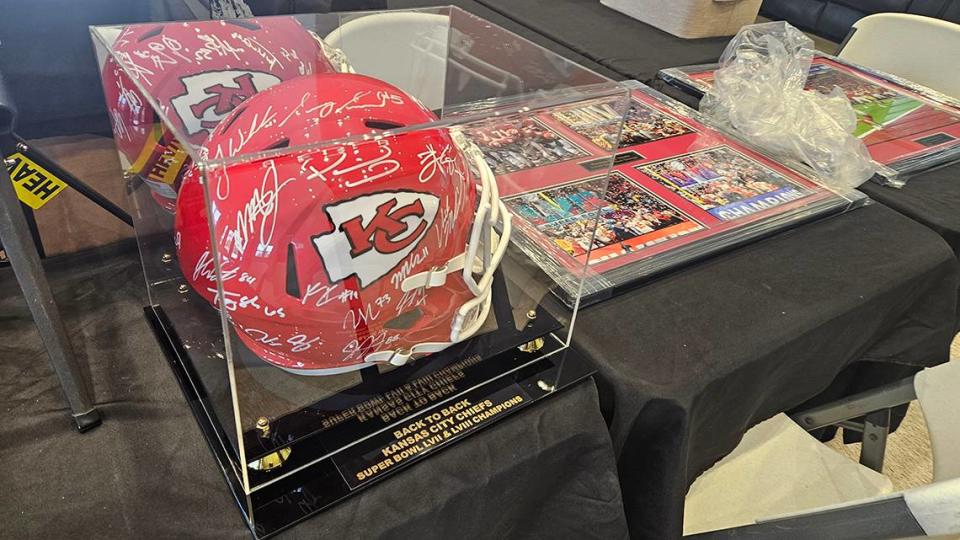

The Browns expected Saturday’s event to surpass the attendance of the first two. Former longtime local sports broadcaster and current podcast host Frank Boal was tapped as master of ceremonies. Of course, a silent auction included Chiefs memorabilia and military-themed items. A live auction and live band and other Derby-related activities were scheduled.

In between reading emails, Pat pointed to the large barn area that would be transformed into a party space. About 400 to 450 people were anticipated, she said. It’s the nonprofit’s biggest fundraising event. War Horses for Veterans’ Derby Day party isn’t the only one in town. But it is up there as one of the most important.

“It’s a big deal,” Pat said. “They put a big floor down out there and we hang lights out there. It turns into a wedding venue.”

Gave Iraq veteran direction after divorce

During my visit, I met Jay Williams, a 38-year-old Army vet who went on a couple of tours in Iraq during Operation Iraqi Freedom. He shared the story of how War Horses for Veterans changed his life.

After a divorce, Williams said he was in a really bad mental space. Prescribed medicine did little to improve his state of mind. He moved in with his mother at her residence in Florida before coming here.

Williams said he came to Stilwell in 2017 with less than a dollar to his name and just a few possessions. He hasn’t left since.

“I came here with 78 cents and a duffel bag after the divorce and fell in love with the place,” he said.

Before he relocated to Kansas, he’d visited the farm as part of a live broadcast with a military radio crew that he worked for at the time. About a month later, he called the Browns inquiring about job opportunities in the Kansas City area.

Williams lived with the family until he found employment and saved enough to move into his own place.

“They flew me back and I stayed with Pat and Andy for three months,” he said.

Williams is War Horses’ media director, videographer, photographer and sometime groundskeeper now. He’s appreciative of the position he’s in.

“I get to capture all these guys and the change from where I was at the bottom of the barrel,” he said.

Williams’ story is just one of showing the important mental health work done by this nonprofit. Thanks to the kindness of the Browns, Williams couldn’t think of any other place he’d rather be, he said.

“I traveled all over the world and ended up here,” he said. “I’m not going back down south, I can tell you that.”