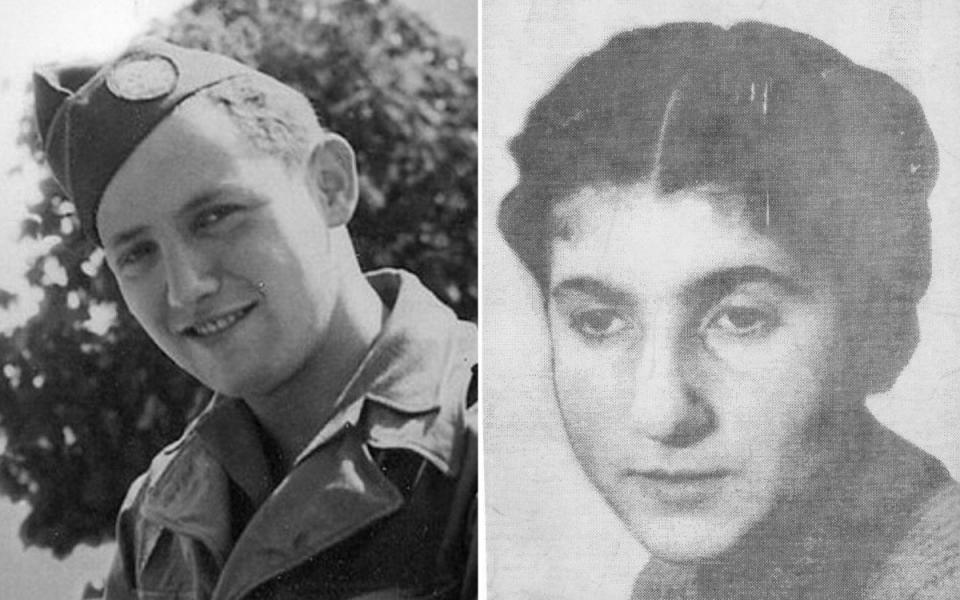

‘We fell in love as prisoners in Auschwitz – then reunited in our 90s’

David first saw Zippi in early 1943. They were at the ‘sauna’ Birkenau, the largest camp in Auschwitz, where workers submerged clothing of new arrivals in steam kettles, disinfecting them with the same Zyklon B pellets used in the gas chamber. Still, this was one of the few warm places there during that unforgiving Polish winter. David was 17 and relatively well fed, his striped uniform neat and clean. Perhaps this was why he stood out.

Sometimes at night he was summoned out of his bunk to sing for the guards. His tenor was beautiful, operatic. It had earned him audiences in his home town of Warsaw. He dreamed of singing opera in New York one day.

Here, he remained a soloist, still a star of sorts. When Zippi showed up, he could almost forget where he was. She gave him something to look forward to. At 4ft 11in, she was petite but sturdy. Her brown eyes were sharp and she moved with a self-assurance that was rare here.

She wasn’t supposed to be in this all-male part of the grounds, yet she’d made a habit of getting herself into places where she shouldn’t be. She was 25 but she’d been like this as a young girl in Slovakia too. If anything, her tenacity had grown. Usually she craved structure and order, but the boy in the ‘sauna’ seemed sweet, eager. Something about him made her reckless.

Zippi had arrived at Auschwitz in a cattle car. It was March 1942. Germans dressed in dark-​green uniforms commanded her to ‘get in line!’ It was the first time she’d encountered the SS.

They chased her out of the railway cars using batons and German Shepherds, herding her and the other women down muddy roads to a gate surrounded by barbed wire. Unnerved and hyperalert, she passed what looked to be corpses lifting massive stones. She’d learn that these were the camp’s inmates. Soon she’d be among them, a silhouette of the living.

A decade earlier, Zippi had been sunbathing by the Danube. An athletic young woman, she loved sport and camping. She’d studied at technical college, the first woman in the region to finish a graphic design apprenticeship, and she was planning to build a life with her fiancé Tibor. Now, he was imprisoned, and her birth name, Helen Zipora Spitzer, was struck from the record. She was now simply Prisoner 2286.

Her new home was Block 9 in Auschwitz I. Four women shared a mattress, and bunks were stacked in threes. Zippi opted for the top one, at least she’d have a sliver of air. Prisoners of war had slept on the spot they now occupied, voices whispered at night. They’d been gassed. One night, Zippi went to the old-​timers for information. What do you know about this place, she asked.

She didn’t discriminate among her sources. She approached political prisoners, Jehovah’s Witnesses. She’d learned to be curious as a child; befriending both Jews and gentiles. And now she turned her focus to collecting friends.

She volunteered to join the ranks of the wrecking Kommando, women who broke up bombed houses. She wanted to see why so many who left to work never returned – and discovered that debris often dropped on them. Many were left to die.

Zippi was certain she could improve the situation. Using a battering ram, she positioned herself at the front of the group and as fragments of brick and stone wall crumbled down, they all jumped back, learning to work in sync.

The SS officers were pleased; productivity improved and fewer died. But one day in June, Zippi fell. Gravel rained down, then part of a chimney crashed on to her back. The guard in charge couldn’t afford to lose her – she was a workhorse. Frantic, he searched his bag and found two aspirins.

She struggled to her feet, forcing her curved back upright, and in agony went to the infirmary where the doctor, a Jewish inmate, smacked her across each cheek. This was her treatment. Zippi was sent back to the barracks. Weeks later, inmates in the infirmary were gassed to death. Zippi was forever grateful to that doctor.

With her back crushed, she asked a political prisoner who worked in the camp offices for help finding indoor work. She wanted to use her skills. Days later an officer approached her. The SS were running out of prisoner uniforms and needed someone to paint a red stripe on the back of new inmates’ dresses to distinguish them from civilians – they needed someone to mix dry paint with oil.

By midsummer, word got round that Zippi was organised and reliable, with a talent for design. Yet her health was now poor. Her mouth, tongue and gums were so covered in pus that she couldn’t swallow, likely due to dental abscesses. Later she contracted malaria. She found ways to mask her afflictions, using red powder from her work tools to rouge her cheeks with a healthy looking glow, but in August 1942, typhus spread through the camp. At night she shivered so violently that she was ordered to Block 27, where sick inmates were sent. With no medicine or water, most lay on mattresses waiting for death.

Her new friends brought her sardines and sausages, stolen from the SS canteen. But Zippi could no longer even see straight. Sixteen years earlier, her mother had contracted tuberculosis and was sent to the mountains, never seen again. She died at 29. Zippi, sick with typhus, was only 24.

Weeks later, guards dragged her out and deposited her by a wall alongside other withered women ready to be transported away in trucks. For weeks Zippi had seen the trucks roll away packed with sick women, then return bearing only old uniforms. She was so sick that her eyes barely worked but she could make out her friend, Hanni Jäger, a political prisoner who worked as a secretary. Hanni was on her way to lunch.

‘Look, Hanni, I’m here,’ Zippi croaked. Hanni recognised this frail wisp. She knew that if Zippi boarded a truck she’d never return, and she ran to her boss. Zippi was healthy, Hanni insisted; the SS needed her skills.

Hanni’s boss sent an officer to check whether Zippi really was of use. He took her to the barracks. ‘Climb up and down from the bottom bunk to the top,’ he ordered. Zippi was weak but relentless and she forced her 70lb body to move. Then he ordered Zippi to jump over some wide ditches on the road. Zippi forced herself. Finally, he took her to the infirmary where a nurse, another acquaintance, took her temperature. ‘Zippi,’ whispered the nurse. ‘I shall say nothing.’ The nurse stalled until the trucks had gone, then assured the officer that Zippi didn’t have a fever.

The trucks transported 2,000 prisoners to the gas chambers that day. The rest of Zippi’s typhus spell was a blur. Soon after she was assigned a role as assistant to Katya Singer, a Jewish prisoner responsible for helping to establish a camp office.

She continued to paint stripes but she was also responsible for the Hauptbuch, the general ledger of prisoners. In a column identified as ‘unknown corpses’, she kept track of the prisoners sent to the gas chamber. The SS also provided Zippi with lists of living people and told her to mark them with a black cross. These were the doomed.

She focused on using her influence to shield unhealthy prisoners by giving them office jobs. There, they could recuperate and she could find them safer Kommandos.

Meanwhile, she sent notes to her brother Sam, her surviving relative, expressing coded warnings. His postcards brought her some relief – but in one, he broke the news that Tibor, her fiancé, was dead. The news was devastating. But she tried to hide her grief, telling no one.

Zippi often found herself at the ‘sauna’, where she’d collect data or drop off reports. Sometimes she woke early to shower there before roll call. Her new role afforded her greater freedom to move around camp.

Then, in early 1943, she spotted David. Among the walking corpses, he stood out. David knew that Zippi was no regular inmate too. She was ‘Zippi of the office’.

For weeks they stole glances. David would brush past, she’d murmur hello. She was pursuing him, he thought, elated. He’d had one romantic liaison back in Warsaw. Could it happen here, of all places? Meanwhile, guards circled.

Eventually, someone made an introduction. That first exchange was brief – just long enough to agree to speak again. They began to exchange notes through messengers. Small scraps, nothing that might incriminate them.

One Sunday in March 1943, David had finished his work early and lay on the concrete floor of the ‘sauna’ to rest. But he drifted off. When he woke he was late for roll call. Outside the window, guards paced, batons in hand, looking for him. Panicking, he crept outside, trying to slip in unnoticed. But they spotted him. A guard dragged him over. ‘This is it,’ David thought. ‘They’re going to kill me.’

‘One move and you’re dead,’ the officer said, poking David’s ribs with a meat hook. David willed his body not to move. Then the officer winked at him – he sent David back to his bunk. David was baffled. Surely his punishment wasn’t over.

Days later, a guard slashed a whip across his hands 10 times. Then an officer ordered him into a room. David saw a noose. Gallows had been set up. Some SS men stood by. One tightened the noose around David’s neck. An officer kicked a plank from under David’s feet. ‘This is it,’ he thought. But he dropped down into a hole at least six feet deep. The SS men guffawed at their joke: the noose hadn’t been tied.

The mock hanging was his initiation into the Strafkompanie, the penal colony for inmates who’d committed serious crimes. He was admitted on 19 March 1943, sent to dig ditches. He was whipped when he moved too slowly, or too fast. He stopped singing.

Three months passed. Survival was minute by minute. And then one day, without warning, he was suddenly ordered back to the ‘sauna’ without explanation. His exchanges with Zippi continued, as though they’d never stopped.

Every time David was afraid that he was in some kind of trouble, he’d tell her about it, and his troubles would evaporate. He told her about his past too; visits to the opera with his father, old memories.

He wanted to impress her. He saw all sorts of treasures at the ‘sauna’ – watches, jewellery. Could he bring them to her? Zippi declined. She had no patience for such frivolousness. In February 1944, about a year after they’d met, she decided it was time for more. She told David of a place where they could meet for some privacy together. For the first time since he could remember, he looked forward to waking up.

He arrived at the designated spot, near Crematoriums IV and V, heart pounding, and found a makeshift wall. Behind it was a nook. Zippi had taken packages of inmates’ clothing, which had been confiscated upon arrival, and used them as makeshift bricks, creating a ladder and a ledge to climb on to; a private sanctuary.

They met there once a month, limiting their time to an hour. They exposed little skin, removing only what they had to. Zippi paid for inmate guards to keep watch. At first, they didn’t talk much. But gradually David told Zippi about being a child star. Zippi wanted to hear him sing, and he obliged.

One day, she taught him a Hungarian song, Evening in the Moonlight: ‘What does she dream about in the night? That a prince might arrive, riding a steed of snow white.’

Music brought them both pleasure. So they often sang together. Sometimes they even laughed. And they kissed. By the summer of 1944, rumours were rife: the Allies were beating the Nazis. And yet the volume of bodies burned in Birkenau was overwhelming; it created such a stench that it felt often impossible to breathe.

In December, the sounds of artillery changed too. The SS men grew nervous. Zippi told David that soon everyone would evacuate. They wondered: where would they meet again?

David suggested they meet at the Jewish Community Centre in Warsaw, or where it had once stood. The city was his former home. Zippi agreed. After this was all over, they promised, they would find each other.

By the time Zippi was liberated, postwar pandemonium had spread. To get to Warsaw, she would have to travel 435 miles through mayhem. Still, Zippi had made a promise to David.

She travelled with another former inmate, Sara Radomski, who had been David’s childhood friend. The journey was dangerous; they were easy targets for desperate refugees and savage soldiers, and Sara was sick and weak. But Zippi supported her.

When they finally arrived, Zippi found a city hollowed out by war. The Germans had eviscerated it. There was nothing resembling a Jewish community centre. Instead, soup kitchens served as gathering points. Yet Zippi was patient. She waited for David. And she waited.

But David never came.

David’s departure from Auschwitz had taken a different turn. Herded into a cattle train with 100 other inmates, he was sent to a satellite camp in Bavaria but the train was attacked by Allied aircraft. The Germans stopped repeatedly, using the prisoners as cover.

At one stop, David noticed that the SS guard nearest to him looked unwell and terrified of the air raids. He snuck up behind and smacked him over the head with a shovel, then bolted into the darkness.

Eventually he heard his train chugging away but he kept moving. Finding an empty barn, he went to shelter. Finally, he was free. As he lay on the hay, he thought: where do I go from here?

When he’d suggested to Zippi that they meet in Warsaw, it had seemed like a natural destination, familiar. But now, he felt repelled by the city. He wanted a fresh start. He imagined the United States, his childhood dream.

After days of waiting, Zippi finally admitted that David wasn’t coming. She considered settling back in Bratislava, her hometown, but instead found purpose in Feldafing, a Jewish displaced-persons camp in Bavaria, where she prided herself in her work, distributing food to pregnant women, and she enjoyed bathing in Lake Starnberg nearby.

One day Zippi noticed a figure struggling in the water. She dived in and hauled him ashore. His name was Erwin Tichauer. He was a scientist by trade, but currently head of security at the camp. Tanned and muscular, with curly hair, he was soon infatuated with this self-assured woman who repeatedly turned down his gifts of stockings.

One day Zippi ran into a friend at the camp who had news of her old lover. David was in Paris, the friend said. He’d joined the US Army and had been stationed there for months. He was having a very good time, her friend added.

Zippi absorbed this news. So, while she’d been in Warsaw waiting, he’d been gallivanting around. Zippi was 26, by then; she hadn’t intended to remain single. But Tibor had died. Then David had left her waiting… Erwin cared for her. He was kind and handsome. In February 1946, they married.

Unbeknownst to Zippi, David sometimes found himself in Feldafing around this time running errands. But their paths never crossed.

In June 1950, Sara Radomski arrived in the United States and learnt that her old friend David now lived in Pennsylvania. She called him and they caught up.

He had been based in France, with the army, before emigrating to New York where his aunts lived, he explained. He’d plunged into life there; dances, parties, making a living as an encyclopaedia salesman, until his work as a cantor took off.

Zippi was alive, too, Sara mentioned. She told David they had gone to Warsaw together after the war, but he’d never turned up. If David felt a stab of regret, he never admitted it. He was married by then too.

But afterwards, David thought more about Zippi. A question had always nagged at him: how was it that he’d survived Auschwitz for years? Looking back, it seemed as though a guardian angel had looked after him.

David decided to give Zippi a call.

When David telephoned, Zippi didn’t know what to say. She hadn’t heard his voice in years. And during their time together, they’d mostly whispered. Now he sounded louder, confident. Erwin listened in from the other line. And why shouldn’t he? Zippi thought. She had nothing to hide.

David told Zippi about himself, about America, about his wife, Hope, as though casually catching up with an old friend. Not once did he apologise for not going to Warsaw. Zippi tried to shrug it off. But when David asked if he could visit, she said no.

Disappointment lingered on both sides afterwards but Zippi decided to have no more contact. She and Erwin were embarking on their new life.

They settled in Australia, then in Texas for Erwin’s work. Around that time Sara contacted her again, mentioning that David still hoped to meet. It happened that Zippi and Erwin were planning a trip to New York. Zippi hesitated. But perhaps enough time had passed. All right, she told Sara. She would meet him in Manhattan.

By then David was in his late 30s. The last time he’d seen Zippi, they’d been 20 years younger. What would she think of him now?

Arriving first, he waited in the hotel lobby they’d settled on. He searched faces. Would they recognise each other immediately?

He waited and waited. Zippi never showed.

Not long before that, David had returned to Auschwitz. ‘I just wanted to see,’ he would later say with a shrug. ‘Life pulls you back.’

For years he’d been ashamed to discuss his past. But gradually he shared his story, giving talks in libraries and synagogues, later writing a memoir. Zippi appeared on only a few pages as ‘Rose’, a woman with mysterious allure.

Zippi had a book of her own. She’d authorised some historians to write it, based on interviews about her memories of Auschwitz. Yet she never once mentioned David.

David discovered Zippi’s book in 2011 and phoned her. Again he wanted to know if he could visit. This time, Zippi wasn’t as against it. Erwin had died years earlier; she didn’t have to worry about disrespecting him. Still, it would be five more years before she finally agreed.

On a sunny afternoon in August 2016, David and two of his grandchildren drove from Pennsylvania to Manhattan, where Zippi now lived.

David was quiet during the ride, not knowing what to expect. Arriving, he was surprised by the darkness of Zippi’s apartment. A frail, grey-haired woman lay in bed, a carer at her side. Zippi could hardly move. What if she didn’t remember him? She was almost 98.

Leaning towards her, he said his name, ‘David Wisnia’. Zippi lit up. The connection was instantaneous. Over and over, she repeated: ‘I waited for you in Warsaw. I waited and waited.’

David tried to explain. I drove to Feldang but I didn’t know you were there. ‘Isn’t life strange?’ she said with wonder. Then Zippi repeated that she’d waited for him. Didn’t he remember their promise? David tried again to explain. He was 18, a kid. Poland had symbolised the death of his family. He’d needed a clean slate.

He reminded Zippi that he’d tried to see her years before in New York. She hadn’t shown up. ‘It was brave of me, not to go to you,’ Zippi answered. To break a promise was against her character, but she had to respect her husband.

She told David about Erwin’s battle with Parkinson’s, how she was now beginning to forget things. She was, after all, older than David. ‘You’re a young rock star,’ said Zippi. ‘You were a young chick, too, I remember it well,’ David said, laughing.

‘Do you remember our meetings?’ he asked. ‘Of course!’ said Zippi. ‘We went into an opening. I remember the little window; so much climbing to get there. And then we kissed.’ David chuckled, sheepish; his grandchildren were listening.

‘How was I in Birkenau? Do you remember what I looked like?’ she asked. David looked awkward, a teenager again. ‘You were good-looking!’ From her pillow, Zippi smiled.

Then David couldn’t contain himself any longer. The question had been haunting him: how had he made it out of Auschwitz? Was she responsible for his survival?

Zippi held up her hand to display five frail fingers. ‘I saved you five times,’ she said. David gasped.

‘Whenever they selected prisoners, I looked for you,’ she continued.

‘So when I overslept and ended up in the penal colony, you’re the one who took my name out?’ ‘Yes,’ she told him. It had been her. ‘I loved you,’ Zippi admitted softly. ‘Me too,’ David whispered back.

Zippi asked if there was anything she could do for him. ‘Nothing,’ said David. He only wanted to show Zippi his grandchildren, the lives she’d made possible.

Before he left, she asked David to sing to her. As his grandchildren looked on, he chose the Hungarian song she’d taught him those years ago. He reached for her hand: ‘Evening in the moonlight, What does she dream about in the night? That a prince might arrive, riding a steed of snow white.’

He hadn’t shown up in Warsaw. But he hadn’t forgotten, either.

Lovers in Auschwitz: A True Story, by Keren Blankfeld, is out on 25 January (£22, WH Allen). You can order a copy here