People Are Calling George M. Johnson's YA Book An "Instant Classic," And Yet It's Getting Banned Across The United States

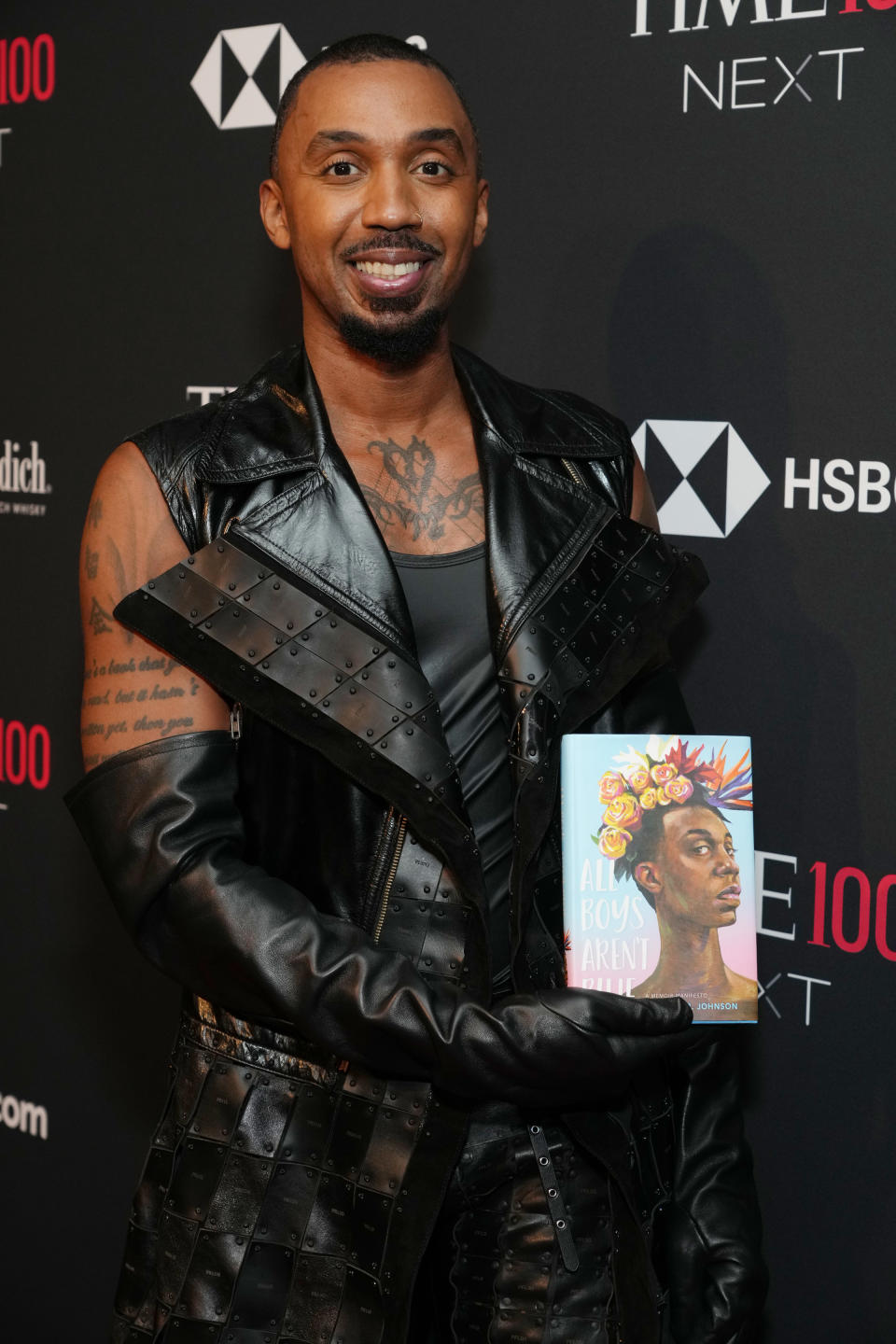

It's not every day you write a book that ends up being the second most banned and challenged book in the United States. Enter George M. Johnson. The author, journalist, and activist published their memoir, All Boys Aren't Blue, in 2020. Filled with coming-of-age stories, including their experience with sexual assault and having consensual sex for the first time, the young adult book quickly became fodder for some parents who argued that it has no place in the hands of young readers.

For Black History Month, I spoke with George M. Johnson about creating such an impactful piece of literature. The New Jersey native also explained how the ban on their book has impacted them personally and shared their vision for the future of Black queer people. Read what they told BuzzFeed ahead.

Editor's note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity. It includes discussions of rape, abuse, assault, and suicide ideation.

BuzzFeed: You share a lot in your memoir, All Boys Aren’t Blue. What was most cathartic for you to share?

George M. Johnson: The part about my history teacher who said that he would have owned slaves had he lived in the 1800s. I never mentioned the teacher's name, but a couple of months ago, a person living in New Jersey reached out to me. She said she saw the controversy around my book and decided to read it. After she read about the high school I went to, she DM'd me and asked, "Was your teacher's name so and so?" I said, "Yeah." She said, "Well, that person is a relative of mine. We had interesting family conversations about his ideas and racism. I'm so sorry you had to experience that, but just know that was the type of person that he was, and be proud that you recognized it and that you called it out."

"I couldn't have foreshadowed that a nationwide book ban was coming."

Was there anything in the book that you were hesitant to share?

Yeah, my first sexual experience. It has become a point of controversy. When I first wrote the book, I did not write that chapter as vividly. I wrote it very cerebral and very technical [when I was describing] what was happening. My editor pushed me and said, "It's okay for you to say it, and to tell the truth."

In this country, sex is still taboo. Sex education is still taboo, too. Sexual assault and rape culture is ingrained into the history of this country. Anytime you try to talk about those subjects, we're taught to place blame on ourselves for the circumstances that happened when, realistically, it is [the blame of] a society that denied us the resources to understand how we should handle those situations to protect ourselves and others.

All Boys Aren’t Blue has moved so many people, especially Black and queer people, in a positive way.

The resounding feedback that comes to me is, "This book saved my life." I get that from teen readers. I've gotten emails from them talking about their suicidal ideations and feeling so alone. They share how the book gave them a sense of personal identity and an understanding that they were perfectly made the way they are.

A few of weeks ago, someone wrote a beautiful review of my book. At first, they said they weren't sure why I included the parts about losing my virginity or my sexual assault in a young adult book. Then, they said they challenged themselves because the book helped them to realize something that happened to them when they were younger that they had been thinking wasn't assault, actually was. That is why it is important.

"To be unapologetically Black and queer is to choose your happiness over your safety."

There are quite a few people who feel your book isn't appropriate for young adults to read.

If you ask those same people when was the first time they had sex as a young adult, they'll refuse to answer it. Why? Because they know what age they were, what their bodies were going through, and what they were feeling at that time — the same way I did. We know that there's a high percentage of children and young adults who experience sexual assault. This information is necessary.

When you block young adults from getting proper resources, they're getting it from people in their classrooms and at their lunch tables, who may not be giving them accurate information. The lie is that my book is introducing them to these topics. Most young adults already know. They just want clarity and that's what [my book provides].

How has the book ban controversy affected your personal life?

I'm a target because of [it]. Even as opportunities are afforded to me, my safety is not being afforded to me. My visibility doesn't give me carte blanc safety, it has reduced my safety. I get death threats and followed in the airport from people who recognize my face. My family also gets threatened online. I want to be clear: I'm paraphrasing [author] Da'Shaun L. Harrison [who says], "To be unapologetically Black and queer is to choose your happiness over your safety."

In my opinion, All Boys Aren't Blue is now part of the great canon of Black queer literature. It will serve as a point of entry for generations to come.

I'm fortunate that people took to the book in this way and that it has become a powerful force. Not just in Black queer culture, either. All Boys Aren't Blue was just on a poster board in Congress yesterday for a bill introduced by [US representative] Ayanna Pressley, who's trying to stop book bans. [An excerpt of my book] was read aloud during a Senate Judiciary hearing.

Someone recently tagged me on Instagram and described the book as an "instant classic." I thought, "Wow, people are already looking at this book as something that's going to be around for a very long time." It's been listed as [one of the best] Black queer memoirs of all time. I think about [authors like] Toni Morrison, James Baldwin, Nikki Giovanni — people who made timeless works that are always going to be necessary.

Could you have predicted any of this for yourself?

I knew the book would have its challenges, but I never knew it would look like this. I couldn't have foreshadowed that a nationwide book ban was coming. I never knew that my book would become a part of a cultural topic. I was writing it intending to give my 5-year-old self, my 10-year-old self and my 15-year-old self a voice and ensure that other people out there who were either the parents of the 5-year-old that I once was, or the parents of the 10-year-old that I once was, or the person who is now the 15-year-old that I once was had a resource to understand what they were dealing with.

"The moments when I feel hopeless are the times when I'm most creative."

To that point, with so much going on in the country, from book bans to anti-LGBTQ bills becoming law across the United States, is hope a lost cause?

Hope is a good thing but sometimes hope turns into inaction. What action are we taking to make things get better? When Black folks say, "We made a way out of no way," that's hopelessness, and that's okay. That's dope that we can make a way out of no way. I enjoy any opportunity I get to collaborate on projects where mutual aid is involved and we get to help ourselves out of situations rather than relying on systems that we know ain't never gonna see it for us.

For Black folks and Black queer folks, hope ain't always been the driver. Hopelessness is also a driving force in many of the things that we have today. The moments when I feel hopeless are the times when I'm most creative. I know that my imagination is where my Black liberation resides. When you get a bunch of hopeless people together who are dealing with the same situation, they probably could figure things out in a cool, creative way. Use your creativity to create some of the social change that you want to see in the world.

What is your vision for the next generation of Black queer people?

I think the next generation will be more empathetic and won't get so caught up in the -isms and the -phobias. At some point, it just makes no sense. We are of a shared race, we are all Black. Whether LGBTQIA+ or not, we are all Black. I want Black folks to realize when you're bashing, ostracizing, harming, or violating a group of people that is within your race, you do the work on their behalf. And they say, "Thank you. Now you're next." They don't say, "Thank you" and give you a prize. I hope the next generation realizes we have to protect all of us.

"Let's start telling our stories."

What do you want your contributions to Black history to be?

I want my contribution to be that the stories in All Boys Aren't Blue have always existed. I wasn't the first person to have this story, I was just one of the first people to be able to tell it. We owe a great debt of gratitude to the Black queer people who existed [before us] and never had the chance to share their story. The job now becomes for other Black queer people to share their story. Don't let it just be me, let it be 10, 50, 100 more [books like mine]. Let's start telling our stories.

What does Black History Month mean to you?

Black History Month is a celebration of those who come before us. It's a time to check in with the ancestors and reread their work so that we know how we can move forward. I love the fact that many of us are now highlighting queer folk who were pioneers of Black history. Let's keep sharing as many stories as we can until Black history can't be contained to just a month. Black History Month used to be a day, now it's a month. Let's make it all year.

Thanks for chatting with us, George! Be sure to keep up with George M. Johnson here.

If you or someone you know has experienced sexual assault, you can call the National Sexual Assault Hotline at 1-800-656-4673 (HOPE), which routes the caller to their nearest sexual assault service provider. You can also search for your local center here.

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255. Other international suicide helplines can be found at befrienders.org. The Trevor Project, which provides help and suicide-prevention resources for LGBTQ youth, is 1-866-488-7386.

You can read more Black, Out & Proud interviews here.