Gretchen Whitmer: ‘When Something Is Taken From You, What’s Left Behind Has a Purpose’

Gary Shrewsbury

I love listening to music, but there’s one song that I can’t bear to hear: Sinéad O’Connor’s “Nothing Compares 2 U." Hauntingly beautiful, it was a huge hit in 1990, playing on the radio constantly when I was a freshman at Michigan State University. And that’s why I can’t stand hearing it. Because it takes me right back to the traumatic event that happened to me that year, when I was raped by another student.

At first, I didn’t tell anyone. Not my friends, my siblings, my parents—no one. I felt ashamed, even though I hadn’t done anything wrong. The assault rocked my sense of the world and my place in it. And I was terrified that I might be pregnant with my attacker’s baby. To my immense relief, I wasn’t. But if I had been, I at least knew that the choice of how to handle that situation would have been up to me.

Over the years, I revealed the assault only to a handful of partners, including my first husband, Gary Shrewsbury, and the man I married in 2011, Marc Mallory. Other than that, I didn’t talk about it, and I tried hard not to think about it. My feeling was that bad things happen to people all the time. Better not to dwell on them, but instead just forge ahead as best we can.

Fast-forward more than two decades later. In 2013, I was serving as Michigan’s Senate minority leader, in a government dominated by Republicans from the governor’s office through the House and Senate. That year, the Republicans tried to push through a bill requiring women in Michigan to buy extra health insurance for abortion coverage— even in cases of rape or incest. If you got pregnant from an assault and hadn’t pre- bought the insurance, well, too bad. You couldn’t buy it after getting pregnant, regardless of the circumstances.

This was not only cruel, it was absurd. Did lawmakers really expect women to “plan ahead” for a potential pregnancy resulting from a possible future assault? Passing this law was essentially requiring women to buy rape insurance. It was infuriating.

Polls showed that Michigan voters opposed it too, and Republican governor Rick Snyder had vetoed similar legislation a year prior. But the anti- abortion group Right to Life sidestepped the opposition by gathering enough signatures on a petition to bring the measure directly to the legislature. If the House and Senate passed this bill, the governor couldn’t veto it this time, because it was a citizens’ petition. This was a terrible loophole in the law, an end run on women’s rights. And the Republicans, knowing there was strong opposition to the bill, decided not to hold any hearings on it, to stifle any dissent. They just wanted to get the thing passed.

Those of us who opposed the bill would have only one chance to speak against it, on the day it came up for a vote. My staff and I prepared a speech for me to give on the Senate floor, whenever that day came. I was angry, and the remarks reflected that. They were personal and emotional, but they did not include the fact that I had been raped. Because no one on my staff had any idea that had happened.

In the Michigan Senate, a bill gets read into the record three times before a vote is taken. The first time, the secretary of the Senate just announces its title— basically a heads- up that it’s coming. The second time, the secretary announces that the bill is open for debate. If you want to speak for or against it, you push a button on your Senate desk, which registers your name on an electronic board. Staffers can’t push that button—it has to be you. So, if you’ve popped out to go to the bathroom, or you miss the announcement, or you just don’t get to your desk fast enough, the majority party can “call the question,” cutting off debate before you get your chance to speak. (When the majority is abusing power, this is a move they regularly deploy.) The third reading is when senators get up to speak.

On December 11, 2013, the secretary announced the “Abortion Insurance Opt-Out Act.” Today was the day, our one chance to try to persuade the Republican side how cruel and unfair this bill really was. Not only would it penalize women who became pregnant through assault, it would also affect women who had miscarriages and needed dilation and curettage (D&C) to remove fetal tissue.

I knew that my Democratic colleague Jim Ananich and his wife Andrea had been trying to have a baby, and that they had, sadly, suffered a recent miscarriage. He and I had already talked about how this law would affect them, since their insurance would no longer cover all the necessary medical treatment upon any future pregnancy loss. Don’t get me wrong; I believe that women should have access to abortions and be in complete control of what happens to our own bodies, no matter whether we’re trying to get pregnant or not. But I thought that Jim and Andrea’s story, involving a couple who desperately wanted children yet would still be penalized by this law, might resonate with the other side.

After the secretary announced the bill for the first time, I walked to Jim’s desk, knelt beside him, and quietly asked if he would be willing to speak on the floor about how the law would affect his family. But the miscarriage had happened very recently, and the pain was just too raw. “I’m sorry,” he told me, his face drawn and tense. “I just can’t talk about it.” I told him I understood, and then stood to walk back to my desk.

And that’s when it hit me. Yes, Jim had a personal story that might make a difference if he shared it that day. But so did I. How could I ask him to publicly bare his soul if I wasn’t willing to do that myself?

The secretary read the bill into the record for the second time, and I quickly pushed the button on my desk. My name popped up on the board behind a few Republicans who’d already been slotted in— a common tactic by the party in power, putting their people first so they can front- load the narrative. Knowing I had a short window before my turn to speak, I grabbed my executive assistant Nancy Bohnet and communications director Bob McCann and pulled them into the caucus room.

With so little time, I had to get right to the point. I told them I had been raped in college, and that I was considering talking about it in my floor speech. Then I asked what they thought.

Nancy immediately said, “Don’t do it. It won’t change any votes, and you’ll be making yourself vulnerable.” Nancy, who had been with me for my whole political career— and is with me to this day— is a strong and politically savvy woman. She knew the Republicans would vote party line, no matter what I said in my speech. Beyond that, she genuinely cared about how this revelation might affect me. She was looking out for me.

I turned to Bob, whose face was ashen. “I don’t have any advice,” he said. “I can’t even put myself in your place. You should do whatever you think is right.” We headed back into the chamber, and soon enough, it was my turn to speak. I walked up to the lectern, my prepared speech in hand, still unsure what to do.

“Thank you, madam chair,” I said. “I rise for my ‘no’ vote explanation.” Then I began reading my remarks.

I rise in opposition to the so-called citizens’ initiative before us that would require Michigan women to pay for a separate insurance rider to cover abortions, regardless of the circumstances surrounding their pregnancy.

Apparently, the holiday season of goodwill toward men reads more like your will toward women, as the Republican male majority continues to ignorantly and unnecessarily weigh in on important women’s health issues that they know nothing about.

As a legislator, a lawyer, a woman and the mother of two girls, I think the fact that rape insurance is even being discussed by this body is repulsive, let alone the way it has been orchestrated and shoved through this legislature.

And for those of you who want to act aghast that I’d use a term like “rape insurance” to describe the proposal here in front of us, you should be even more offended that it’s [an] absolutely accurate description of what this proposal requires. This tells women who were raped and became pregnant that they should have thought ahead and bought special insurance for it. . . .

I’ve said it before and I will say it again. This is by far one of the most misogynistic proposals I’ve ever seen in the Michigan legislature.

I delivered my remarks as deliberately and forcefully as possible, letting my anger show. In the back of my mind, though, my thoughts were spinning. For twenty-three years, I had pushed down the awful memory of what happened to me in college. I never in my life imagined talking about it in a public forum. Yet suddenly, in the course of one short speech, with TV cameras rolling, I had to decide whether to reveal my deepest secret to the world. Once it was out, there was no turning back.

My mouth went dry. It was terrifying to think of opening myself up, of telling this room full of mostly men about being assaulted as a young woman. Yet, the longer I spoke, the more I realized I had to do it. With only a few minutes left of my time, I put my papers aside and began speaking off the cuff.

“I have a lot more prepared remarks here,” I said, “but I think it’s important for me to just mention a couple of things.”

I spoke briefly about a woman named Jenny Lane, who had written a letter opposing the bill. I mentioned having “a colleague” whose wife’s pregnancy went awry and required a D&C, taking care not to name him. Finally, I gathered my courage and began speaking the words that I had never imagined saying in public:

I’m about to tell you something that I have not shared with many people in my life. But over twenty years ago, I was a victim of rape. And thank God it didn’t result in a pregnancy, because I can’t imagine going through what I went through and then having to consider what to do about an unwanted pregnancy from an attacker. And as a mother with two girls, the thought that they would ever go through something like I did keeps me up at night.

At the mention of my daughters, my voice broke. I was fighting back tears, but after taking a moment to compose myself, I went on.

I thought this was all behind me. You know how tough I can be. The thought and the memory of that still haunts me. If this were law then, and I had become pregnant, I would not be able to have coverage, because of this. How extreme—how extreme does this measure need to be?

I am not the only woman in our state that has faced that horrible circumstance. I am not enjoying talking about it. It’s something I’ve hidden for a long time. But I think you need to see the face of the women that you are impacting by this vote today. I think you need to think of the girls that we’re raising and what kind of a state we want to be, where you would put your approval on something this extreme.

When I finished my remarks, the chamber was absolutely silent. I quickly turned and walked away from the lectern, my heart pounding. Had I really just said all that? Would it come back to haunt me somehow? It would be on TV and in all the newspapers, that much I knew. With a shock, I realized that I needed to call my dad right away, so he could hear it from me and not from news coverage. My mother had passed in 2002, so she would never know about the assault. And even though my daughters were just ten and eleven, I told them too, as forthrightly and calmly as I could. I didn’t want them learning it from school friends whose parents might have been discussing it.

As soon as I could, I hurried back to my office and called my father. “Dad, I just wanted you to know that I gave a speech on the floor, and it’s going to be in the news, but I shared that I was raped in college.” It’s a truly strange way to have to reveal such a thing to your father, but what choice did I have? He was stunned, and of course upset for me. My dad and I have always been close, so this was a tough moment for both of us.

After all the senators who wanted to speak had spoken, and the vote was finally taken, I was devastated to see that choosing to share my painful secret hadn’t changed a damn thing. Every single Republican, and one Democrat, voted in favor of the bill, which meant I had pried myself open for nothing. My disappointment flared into anger when a Republican senator walked up to me afterward and said, “I think you’re really brave, and I wish I could have voted with you. My wife was raped in college too.” All I could think was, How dare you walk up and say this to me, having cast the vote that you did? It was one thing if people didn’t comprehend what they were voting on. But here was a person who understood, and still chose to vote the way that he did. What hope did we have?

***

The next morning, I headed to work feeling hollowed-out and depressed. What had been the point of laying my soul bare like that? Then, during my drive, one of my staffers called. We had been inundated by emails and voicemails from people all over the country— and even as far away as Tunisia. My floor speech had been shared all over social media, and hundreds of people, including many who were survivors of assault themselves, had reached out to offer words of encouragement and thanks. It was a relief to realize that a moment I had feared was a waste had instead provided comfort, and might actually become a galvanizing force, for many women.

To my surprise, I was invited to appear on The Rachel Maddow Show—not usually something that happens to a state senator. In a short interview, I said we would keep fighting against the law, and that I planned to introduce legislation to repeal it. “Considering the makeup of the legislature, I’m not optimistic that we’ll get it through,” I said, “but I am optimistic, because I know the people of this state are robustly against this legislation, and I believe if we go to the ballot, we can win. But it’s a heavy lift and we’ve got a big fight on our hands.”

I wasn’t wrong about that part. The fight would take years but seeing the reaction of women to not just my story, but the stories and speeches of all who fought against that terrible law, was inspiring. I was determined not to give up until we got it off the books.

Over the next decade, we rolled up our sleeves and got to work. We passed a ballot initiative to draw fair districts, so gerrymandering didn’t artificially keep a minority party in power in perpetuity. When I won the governor’s race in 2018, we used that momentum to strengthen the Democratic Party’s infrastructure, leading to more electoral wins— including turning Michigan for Biden in 2020. And we galvanized voters who cared about reproductive freedom. In 2022, with a constitutional amendment to protect abortion rights on the ballot, voters came out in droves.

For the first time since 1984, Democrats won the governorship, the Senate, and the House. With control of the legislature, we could finally repeal that terrible law.

On December 11, 2023, the ten-year anniversary of the day I made that floor speech, I once again stepped to the lectern in the Michigan State Senate. But this time, it wasn’t to pry myself open or plead for Republicans to pay attention to the needs of women. It was to announce that as governor, I had just signed into law the final bill of the Reproductive Health Act, a new package of laws that would protect the rights of Michigan’s women—and repeal the rape insurance law.

Wearing a fuchsia blazer, surrounded by women, I proudly announced that we were striking down the politically motivated and medically unnecessary laws and restoring personal freedoms for women.

“The moral of this story is, don’t stop fighting for what you know is right,” I went on. “There’s a warning in the story, too, [to] anyone who wants to roll back our rights: Don’t mess with American women. We’re tough and we fight back and we will win. You come for our rights and we will work harder to protect them.” It was one of my proudest moments yet in politics.

When I think back to how depressed I felt after failing to sway the vote in 2013, I remember what a wise therapist once told me. “Everyone is a lump of clay,” she said. “When a lump of clay is hollowed out, it becomes a cup, a vessel.” I love the idea that when something is taken from you, what’s left behind has a purpose. For a long time, I wanted to ignore the terrible event that happened to me in college. But now I recognize that it also helped to make me who I am, a woman who’s willing to fight and not inclined to give up. I’ll always be grateful that I could use that bad experience for good.

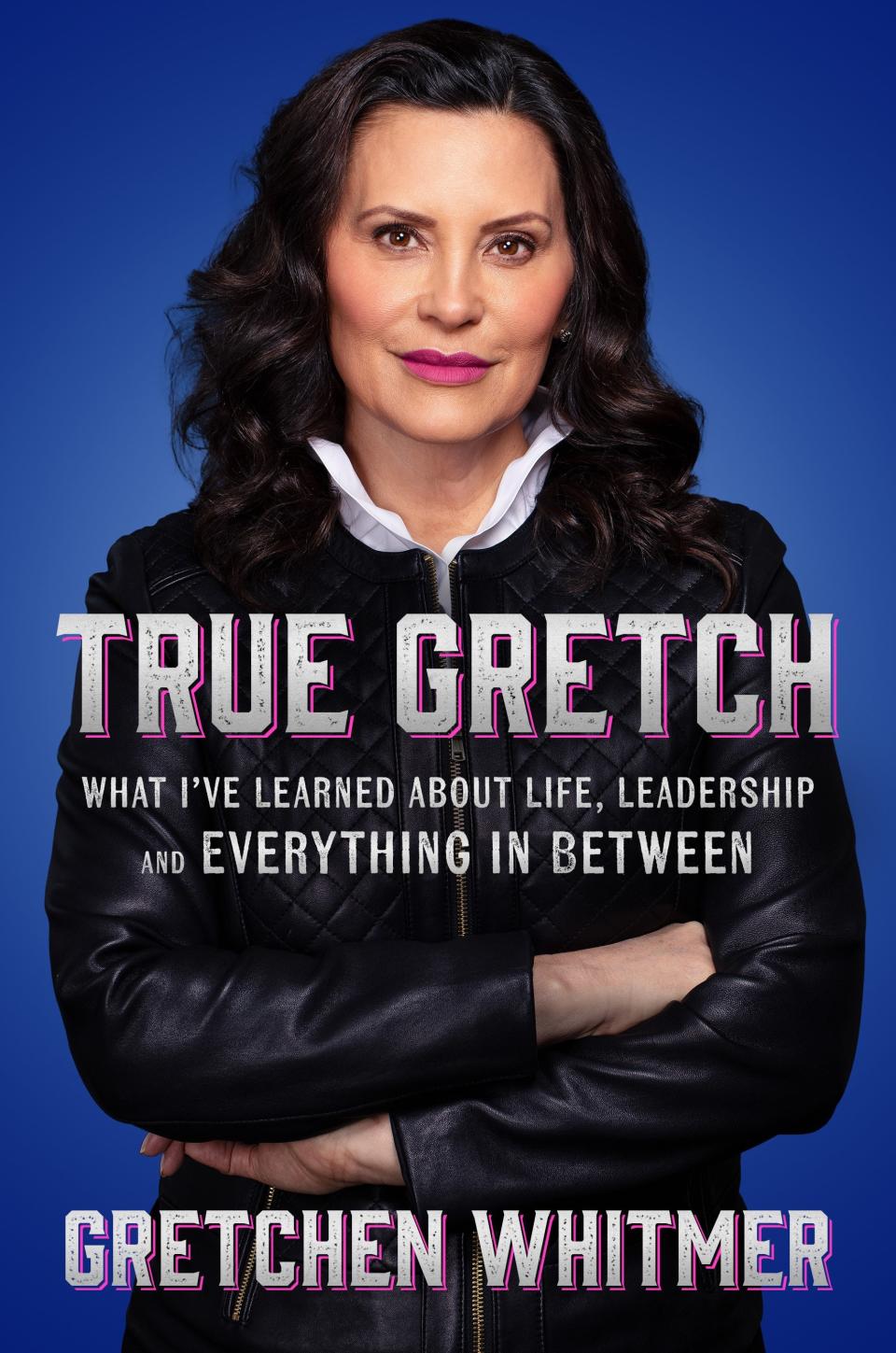

Excerpted from True Gretch: What I've Learned About Life, Leadership, and Everything in Between by Gretchen Whitmer. Copyright © 2024 by Gretchen Whitmer. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Originally Appeared on Glamour