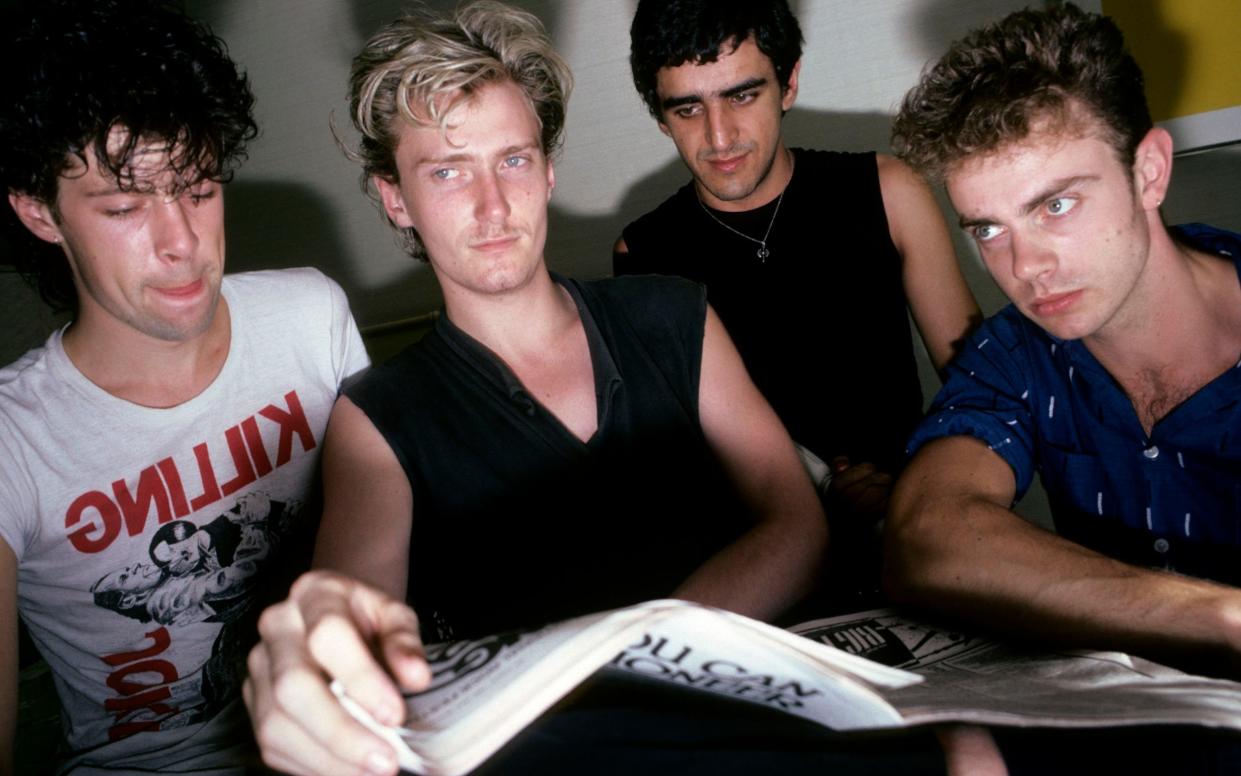

How Kevin ‘Geordie’ Walker made Killing Joke brutal and beautiful – and changed punk forever

With the passing of Killing Joke’s Kevin ‘Geordie’ Walker, aged just 64, the punk generation has lost one of its most original and influential guitarists.

The band’s singer, Jaz Coleman, may have always been the household name and attention magnet in their ranks, thanks to his clown face-paint and apocalyptic exhortations, but it was Walker, with his crunching, “chugga-chugga” style, who gave them their musical muscle. He more or less single-handedly invented the thrash-metal sub-genre, as well as the savage sound of “industrial”.

Hence Metallica covered their song, The Wait, and Nirvana, too, famously based Nevermind’s big-hitting single, Come As You Are, on his riff from the track Eighties, to the point where a lawsuit was threatened, and Kurt Cobain reputedly agonised over whether to release it at all. Even then, Cobain and co would listen to KJ tapes in the dressing room, to gee themselves up to fever pitch before going onstage.

That brutal yet beautiful sound Geordie generated – dense, punishing riffs offset against whirling, textured arpeggiation – has been in my life since I was 15, when I devoured the first two Killing Joke albums, 1980’s self-titled debut, and the following year’s What’s THIS For…!

Like many teenagers in the early 1980s, I was hungry for the next development in punk rock. Many of the first wave’s key players had moved on: both Siouxsie & The Banshees and The Sex Pistols’ John Lydon had acquired guitarists forging a new-found post-punk sophistication (respectively, John McGeoch and PiL’s Keith Levene). Killing Joke, by contrast, pulled off the necessary evolution, while still retaining the political edge and sonically going for the jugular.

While working in a beach shop in Torquay, I remember one of my colleagues turning up bruised but exhilarated after seeing them play in Exeter the night before. To prove it, he sported a Mike Coles-designed KJ T-shirt depicting a Catholic cardinal closely resembling Pope John-Paul II as he strolled between Nazi soldiers giving him the “Sieg Heil” salute – which, to a directionless teenage mind, was every bit as alluring as the music.

It took me a while to witness a gig first-hand: it was circa acid-house, when bassist Martin Glover, aka Youth, had infused a flavour of tribal electronica into their mix, but still it was volcanic and life-changing.

Apart from the odd band hiatus, I’ve seen them play every year or two ever since, never experiencing anything shy of a total battering. One occasion was in a quarter-filled arena supporting superfans Mötley Crüe, another in an even emptier Electric Ballroom as part of a disastrously under-promoted multi-venue festival in Camden. Yet in each case, the performance was full-blooded, as if the house was packed and outside the world was ending.

Often, I’d look aside from Coleman’s visionary histrionics and just watch Walker, mesmerised, as he impassively caressed the strings with such devastating impact.

Having written about Killing Joke many times, my most substantive conversation with Geordie came around 2015’s Pylon album, where the original quartet delivered their fiercest post-millennial music, with Coleman – definitely one of life’s worriers – predicting the Covid pandemic five years before the fact on I Am The Virus, and the guitarist throughout playing in a cacophonous frenzy.

In-person, Killing Joke were (and are?) always hilarious company, party-hearty and extreme, with a knowing sense of their Spinal Tap-esque excesses. For his interview, Coleman had me sit atop a backstage toilet (without a lid), and soon blamed me, personally, for the David Cameron government’s newly revived Trident programme.

Geordie, though, was the opposite of Jaz: softly spoken, often rather giggly, content in a pub corner with a steady stream of vino rosso, but also wonderfully articulate. He explained at length how the “astro-cartography” of the group’s personalities was such that they were perfectly balanced for longevity, with himself and Youth as “very much the happy campers”, and Coleman and ferocious drummer, Big ‘Paul’ Ferguson, as its firebrands. He recalled how he’d first discovered his musical ability while growing up in Newcastle.

“My parents were really good ballroom dancers,” he said, “and grandma was an amazing pianist by ear, so you realised that music’s just kind of in there with you. Then you nag your parents into buying you instruments, which was a bit easier being an only child, and then you find you can actually play the tunes you like on the radio, like [The Move’s] Blackberry Way in 1968. Then you realised it’s just a way of expressing oneself.”

As such, when the family relocated to Bletchley in Buckinghamshire, he resisted joining any groups until he found the right people to make his statement. This only happened after he moved to London to study architecture, and answered an ad in the music press placed by Coleman and Ferguson. This tight, frictional pair had been dabbling in the occult; before any music had been made, torched their shared flat in Battersea in a botched ritual while Walker visited.

“I got this knock on the door at 4 am – ‘The house is burning down’. So I called the fire brigade, pulled my leather strides on, grabbed my electric guitar, and felt my way out through the smoke, to the bus stop across the road. I goes, ‘Where’s Jaz?’ And there he is naked, with his face black from the soot. Luckily the fire station was 50 yards down the road. The only person that got hurt was a fireman after they’d put the fire out – the gas meter exploded, and all the coins hit him.”

Whether by a higher power, or the patronage of John Lydon, who funded early forays in the studio, Killing Joke were soon up and running, filling the void left by the first-wave punk bands who’d successively split up.

Walker claimed to have based his unique, harmonically rich style on the soundtrack music from Danger Man, a 1960s ITV spy series starring Patrick McGoohan. “It had this harpsichord jazz thing running right the way through it,” he shrugged, “and that’s where I got it all from. I threw in a load of classical as well, because I wasn’t into all the usual blues scales.”

The gigs were always riotous, he said, yet rarely unfriendly. “There was one nasty-ish one in Gloucester, where there was a stabbing outside afterwards, but I always loved seeing bouncy boys dancing. I think our music was actually powerful enough to soothe the savage breast, so we didn’t get actual trouble. Troublesome types, onstage and off, but not violent gigs.”

Killing Joke’s inner chemistry was ever-volatile, particularly in the rhythm section. In 1984-85, Youth went off to be a producer, and briefly collaborated with Kate Bush circa Hounds Of Love, which Geordie insinuated was a romantically driven collaboration. “He was straight in there,” he laughed, “like a rat up an aqueduct.”

Walker, however, was a constant presence, even accompanying Coleman on a legendary pilgrimage-cum-escape to Iceland, which he described as “a faerie f______ paradise”. Another ritual reportedly saw Coleman levitating off the ground. “That actually happened,” Walker fervently maintained. “I was there.”

Though the band scored one gothily-tinged hit with 1985’s Love Like Blood, they were ever one of the country’s biggest undergound cult acts, which suited Geordie fine. “If it had all gone according to plan, we’d’ve all been dead by 1986,” he laughed.

Apart from a brief five-year lay-off around the turn of the millennium, when Walker moved to Detroit to raise his son, Killing Joke have never relented, reactivating the original line-up in 2008 and spiriting up some of their most incendiary music across three albums which inspirationally defied any notion of lame heritage-rock.

“We’re really lucky to be in the same band all these years later,” Geordie marvelled, “and new people, young people, are still coming to see us. We’ve achieved that by not queering the pitch, not milking it too much. You have to keep at it. If you’re not surprising yourself when you’re writing, what the f___are you doing it for?”

True to that driven ethos, the last Killing Joke show I saw was amongst the best. Coming out of the gruelling lockdowns that Jaz foresaw, they celebrated the 40th anniversary of those first two albums at the Royal Albert Hall, with the usual gathering of tribes – goths, punks, squatters, ravers and new disciples – convening for one mighty ceremonial party.

It’s hard to contemplate now that such gatherings may never happen again, or that Geordie Walker’s hollow-bodied 1952 Gibson guitar, a scything presence in innumerable lives, will fall silent, no longer to thrill and electrify. The only consolation: he leaves behind a recorded legacy of extraordinarily consistent high quality, which should finally see him instated as one of the true greats of his era.