‘I’m using F1 techniques to power up my work on dementia’

Christmas Charity Appeal 2023

Support our four chosen organisations

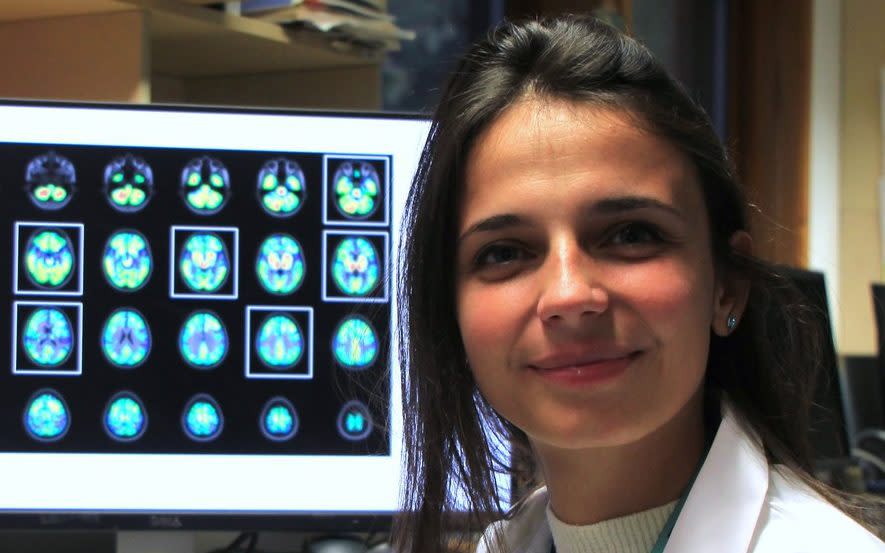

Roaring 1,000 horsepower engines, squealing tyres and the intoxicating reek of exhaust fumes: the world of Formula 1 sounds a far cry from the sterile environment of a medical research laboratory. But Cambridge University scientist Dr Maura Malpetti says the two have more in common than you might think.

When she is not peering down a microscope or theorising about the possibilities of high-tech brain scans in her mission to find a cure for frontotemporal dementia, Dr Malpetti’s favourite topic of conversation is F1, especially her team of choice, Ferrari. Bringing those two interests together could make the difference when it comes to finding a cure.

Frontotemporal dementia is a rare form of the disease which affects about 20,000 people in the UK. The condition, from which Die Hard actor Bruce Willis suffers, can rid its victims of their memory, language, motor skills and even their personality. It also often affects people earlier in life than Alzheimer’s, with patients diagnosed in their 40s, and there is currently no effective treatment to stop or slow down the impact of the disease.

Current methods of measuring brain inflammation are either invasive, involving painful spinal fluid extraction, or very expensive, relying on powerful scanning machines, so using simple blood tests to measure inflammation offers a much better means of screening people.

“The diagnosis is currently quite devastating because it is given without offering a solution,” says Dr Malpetti. “We really need to find something quickly that works to slow down the progression and eventually prevent the disease.”

Real-world setting

With that in mind, the researcher and her team recently set up the Open Network for Frontotemporal Dementia Inflammation Research, a network of 20 centres across the UK to collect blood samples of people with this specific type of dementia and trial the blood tests in a real-world setting.

And then, as part of winning a five-year fellowship from the charity Race Against Dementia, one of the charities supported in this year’s Telegraph Christmas Charity Appeal, Dr Malpetti and her team were mentored by Hintsa – performance and wellbeing experts who work with F1 Teams – and underwent training to find out what skills from the world of high-octane sport could be transferred to the lab.

The F1 team furnished them with insights into organisation, innovation and resilience that have helped to push their medical research to the next level. “I never dreamed you could meld the two fields together,” says Dr Malpetti.

A passion for racing

Born in Italy, the Cambridge University researcher had been raised on a diet of “Schumacher and pasta” and spent her childhood waking up “at the weirdest hours” to watch the Japanese and Australian Grand Prixs with her father. When F1 visited Italy, they would always go to watch the free practice sessions at Monza, and even now the pair still call each other to compare notes before the start of every race.

So when Dr Malpetti was completing a PhD in clinical neurosciences at Cambridge, she was excited to hear about a fellowship offered by Race Against Dementia, which offers researchers the chance to set up their own labs and study a new area of the disease. “When I saw it, I applied with my idea of screening for frontotemporal dementia and I was lucky enough to get picked up,” she says.

As a result, her team then set up a trial combining blood tests and brain scans that found a link between inflammatory cells in the two, among those with frontotemporal dementia, for the very first time.

“I was super excited when the results came through,” she says. “This will be really life-changing if we can translate what we see in the brain scans into blood tests which everyone can access. It opens up lots of really important ways of screening the population.”

But how did the F1 connection make a practical impact in the lab?

Christmas Charity Appeal 2023

Support our four chosen organisations

Firstly, after being taken on a tour of the Red Bull and McLaren factories, Dr Malpetti and her team embraced the benefits of keeping a tidy workspace. “These people work with cars, so there should be oil everywhere, but everything was spotless,” she says. “It really allows your mind to think about the details.

“We have forced ourselves to rearrange our lab so we don’t waste time. We all know where the data are, where the files are. There is very much a Formula One mindset in our labs to make sure we have everything organised.”

Another thing brought back to the lab from F1, she says, is smarter use of space. “The physical distance to move from one place to another in the F1 factory is very short, which allows for quicker decision making. What I’m doing here in Cambridge now is putting all my team around one desk so the communication of ideas is much faster.”

Team effort

While big-name drivers like Lewis Hamilton or Max Verstappen earn the plaudits in Formula One, dousing themselves with Champagne in celebration, winning a Grand Prix is as much a victory for the team as it is for the person behind the wheel. In the weeks between races, colonies of mechanics tinker away at their cars with spanners and soldering irons for days on end in a bid to improve their performance. Dr Malpetti says her team has adopted the same attitude towards innovation in their scientific research.

“Formula One teams learn a lot from other fields such as aeroplanes or the military, bringing a lot of new technologies into motorsport,” she says. “We are doing the same by learning from cancer research, which has been better funded than dementia for many years.” Indeed, it was from seeing how inflammatory immune cells called cytokines could be measured as an indicator of cancer that Dr Malpetti thought to study the cells in relation to dementia.

Dr Malpetti and her team have also borrowed a willingness to adopt new technology from F1. “Something we are currently trialling is using machine learning and AI to analyse all immune cells to see if we can pick up cells that indicate dementia,” she says. “Hopefully in a few months we will have results.”

Resilience

But embracing innovation also has its pitfalls, leading to mistakes which require a degree of resilience to bounce back from. Dr Malpetti says adopting a thick-skinned mindset to these hiccups is something she has borrowed from motorsport as well. “Drivers have a lot of resilience because maybe the car doesn’t work, maybe they crash at the first turn,” she says. “This is important in academia too, as papers get rejected and hypotheses get disproved. It’s important to keep in mind the long-term vision and see those failures and mistakes as bringing success further down the line.”

Finally, she has also introduced weekly debriefs, just like F1 teams do after a race, to discuss what is working and what hasn’t in order to encourage innovation. “Meeting every week to work out where to improve, rather than waiting until the end of the month, creates a much more systematic approach to revision,” she says.

Reflecting on combining her love for F1 and dementia research, Dr Malpetti says: “Michael Schumacher was an incredible team player, always alongside mechanics and engineers to find the best solution and fastest problem solving approach – I aim to approach my research to cure dementia in a similar way.”

Race Against Dementia, is one of four charities supported by this year’s Telegraph Christmas Charity Appeal. The others are the RAF Benevolent Fund, Go Beyond and Marie Curie. To make a donation, please visit telegraph.co.uk/2023appeal or call 0151 284 1927