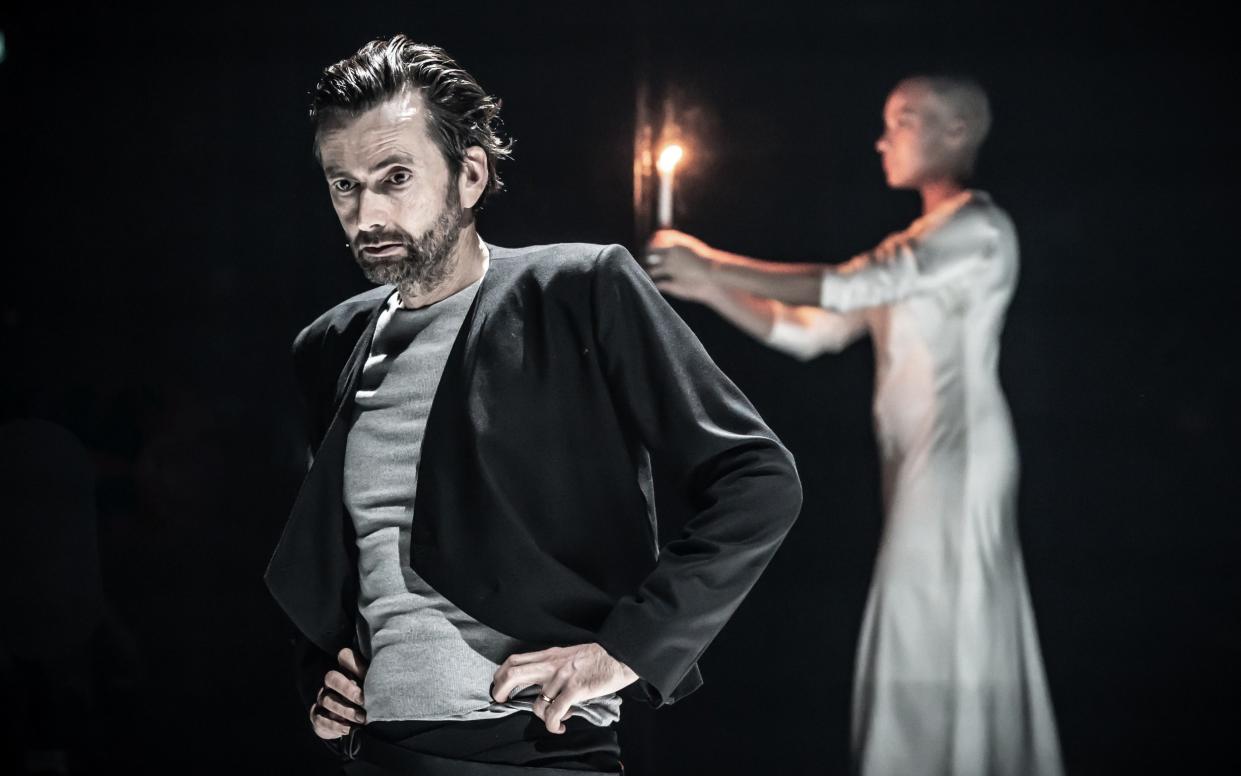

Macbeth, Donmar Warehouse, review: David Tennant triumphs in magical, revelatory staging

In 2008, at the height of hysteria about the new Who, whipped up by his winning turn as the good Doctor, David Tennant delivered a Hamlet for the RSC that had you hanging on every word, soliloquised or otherwise.

Now as enthusiasm surges afresh for the nation’s favourite time-traveller – prompted by Tennant’s brief return to the Tardis – he tackles another mighty Shakespearean tragic role, and delivers no less of a coruscating triumph.

Where Hamlet is the deliberative prince who agonises over merited vengeful action, Macbeth of course is the trusty soldier, prompted by supernatural coaxing to assassinate his king, only then to be seized by a far from feigned madness of stricken conscience. There are usually, and sensibly, gaps between starry attempts at these commanding parts, but the Donmar’s (sold-out) production comes hard on the heels of Ralph Fiennes’ touring ‘warehouse’ version. This account, it should be said, is intimate and experimental where its rival is capacious and more robustly straightforward. Whisper it, though: this one has the exhilarating edge.

And whispering is part and parcel of the enthralling spell cast by Max Webster’s compact, monochrome, chilling revelation of a production. The rising director’s recent West End hit Life of Pi thrived on video projection. Here, the technological marvel is binaural sound (courtesy of Gareth Fry), which entails the audience clamping on headphones as they settle down and results in a maximum-strength Macbeth of imagination-preying force.

It might sound as if we’re in for a souped-up radio play; in that regard, Tennant has already delivered the goods on Radio 4 last year. But the ‘broadcast’ here is of a different order of immediacy – words can be delivered in little more than a hush, and can seem to assail us from all sides, combining too with pre-determined effects (the flap of raven wings, say) and live-produced musical strains and Celtic song. The musicians and other members of the cast are mainly situated at the rear, behind a raised wall of windows, creating a pervasive ghoulish presence.

Those inclined to complain about actors being mic’d-up or a lack of clarity in verse-speaking have their sharp retort here; you miss nothing, and the artifice assists the innate requirement that we be spooked and shaken. There’s at once a sense of eerie detachment and inescapable connection – at times it’s as if we’re eavesdropping, but more than that, especially during the soliloquies, it’s as if we’re in Macbeth’s head and he in ours.

The witches don’t take physical form in the early encounters but are merely words shifting through the misty ether. At the time of Duncan’s murder, Cush Jumbo’s Lady M just stands and listens intently, senses sharpened – we hear every floor-creak and noise. When murdered Banquo confronts Macbeth at the feast, we just hear his groans. In our mind’s eye, from his shrieks, we picture the death of Macduff’s boy.

A sense of mental overload is there from the start as Tennant’s black-kilted and booted warrior, with bloodied hands and face, kneels on a plain white platform stage at a basin to wash (a prefiguring of his later actions), fatigued after battle, the opening reports of which are fed into our ear-pieces instead of being relayed in the flesh.

There’s next to nothing of the cheeky charm that the actor, 52, often brings to the Bard; he has an angular intentness and develops a stronger air of fixity once possessed with the idea of the seized succession, finally attaining a wheeling derangement. The idea that his own lack of progeny is an unhealed wound and the Achilles’ heel of his power-lust is brought home – we see him sit broodingly at one side of the stage, while Cal Macaninch’s Banquo cuddles and converses with his boy. In another telling moment, again, Jumbo – a distinctive English voice in a predominantly Scottish company and terrific throughout, at once thoughtful and heartless – strokes the air, as if still hankering for the child she lost, as she sways in her somnambulant state.

None of this is done heavy-handedly; it’s as if the play is being discovered for the first time – the directorial concept never impedes the fluency and spontaneity of the performances. For almost two hours, you’re held in the play’s grip until Tennant’s physically prostrate and profusely bleeding monarch lies felled, and alone, like a sacrificial victim; we gaze upon the corpse, while hearing, as if through his dying senses, the final exchanges between the departed company – an act of risk-taking theatre that also feels darkly, magically, like real-life.

Until Feb 10 donmarwarehouse.com