The Mediterranean Diet Isn’t the Healthiest Diet out There

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

Depending on who you are and where you’re from, nutrition advice can feel helpful—or make you think everything you’ve ever eaten is wrong. Eating well can mean something different to each of us, and the foods you grew up enjoying play a huge role in determining what you want to eat. When nutrition advice makes your favorite foods seem like the enemy or excludes your heritage altogether, you may start to think you’re the problem. But no: Experts say biases are baked into popular nutrition advice—and getting past them can bring everyone a whole new understanding of food.

Putting diversity on the table

Nutrition advice has to come from somewhere, so we turn to experts. However, 80% of registered dietitians in the U.S. are white and only 3% are Black, according to the Commission on Dietetic Registration. This can affect perspective and messaging. “The top-down effect contributes to a very narrow definition of what ‘healthy’ means. The lack of nuance affects policy-making and, on an individual level, sends the message that to be healthy you must look and eat like white women,” says Laura Iu, R.D., owner of Laura Iu

Nutrition in New York City.

Food scientist and nutrition expert Kera Nyemb-Diop, Ph.D., recalls having been one of two Black students in a human nutrition course in which a professor described African food as “gross.” In addition to the comment being inappropriate, she says, she felt that it was uninformed—there’s huge diversity in foods from the continent of Africa. And what’s said in classrooms, she points out, can have a deep impact on perceptions of cultural foods.

“The gaps are in the people giving the advice, which affects the practical application,” explains Allyson B. Johnson, R.D.N., a Black dietitian who is the nutrition services manager at Loma Linda University Medical Center. When people who give advice lack exposure to and understanding of other cultures, they often rely on stereotypes to make suggestions. “In the U.S., society stereotypes foods like Chinese and Indian and soul food as being too oily or too salty. These assumptions grossly misunderstand that our cultural dishes are vast and complex, are rich in vitamins and nutrients, and include whole grains, proteins, and vegetables,” says Iu.

The problem with perception

Many foods from Black and brown cultures have simply not been studied comprehensively. “Nutrition scientists will say the research is backed by evidence-based practice, but the research is done on Western foods, by white people,” says Nyemb-Diop, who is of both African and Caribbean descent.

For example, in a study published in the Journal of the American Heart Association that found a decreased risk of cardiac arrest for people who adhered to the Mediterranean diet versus those who didn’t, Nyemb-Diop explains that researchers divided various cultural foods into categories and compared them with the most nutrient-dense foods in the Mediterranean diet. Southern food, often linked to Black food culture, was explained as a diet relying “heavily on added fats, fried food, eggs and egg dishes, organ meats, processed meats, and sugar-sweetened beverages.” Nyemb-Diop says this study led many publications to print headlines that said things like “Too much Southern food can cause a sudden heart attack.” She argues that the researchers “mischaracterized Southern foods” when in fact Southern cuisine features an array of vegetables, including collard and mustard greens, peas, okra, cabbage, and sweet potatoes.

Additionally, Nyemb-Diop notes, the historical foods of communities of color often are not deemed acceptable until they’ve been “gentrified” and absorbed into mainstream culture. “I see cultural foods being deemed unhealthy all the time until they’re promoted by white influencers,” agrees Iu. For example, quinoa, a staple food in Central America for thousands of years, became a popular grain alternative elsewhere after being embraced by white health and wellness experts. And “turmeric and milk was part of Indian food culture and is now sold in some Starbucks,” Nyemb-Diop adds.

Shifts happen, but most often this occurs without acknowledgment of the indigenous cultures newly popular foods come from, and generally only after white health and wellness professionals embrace them, Nyemb-Diop says. When influencers fail to acknowledge foods’ cultural roots, it comes off as cultural appropriation, Iu notes: “Recently I noticed white influencers on social media using rice paper for spring rolls and dosas and claiming them as their ‘low-carb’ inventions when in reality these traditional foods are not for white influencers to tokenize and appropriate.”

There’s more than one way to eat healthy

Health food trends come and go, but this year the Mediterranean diet was named the best diet by U.S. News & World Report for the fifth year in a row. It’s hard to avoid the perception these days that this is the one superior way to eat.

It certainly is healthy: The Mediterranean diet is predominantly composed of plant-based foods like legumes, nuts, and grains with a moderate amount of dairy and lean proteins such as seafood and chicken. It includes very little red meat and few sweets, and its primary fats come from olive oil. The diet was developed from the work of researcher Ancel Keys, who, in 1958, conducted studies in seven countries and found that people who adhered to this eating style had a lower incidence of heart disease and better overall health.

However, critics claim that despite the health benefits of the Mediterranean diet, to center it as the best diet is to put primarily Caucasian nations on a pedestal and look down on foods of other countries. The Journal of Critical Dietetics points out that the participants in Keys’s studies were mostly white. Some countries largely made up of communities of color, such as Egypt, Libya, and Turkey, are technically Mediterranean countries, but foods of theirs such as rice, kebabs, and pita bread are not included in this idealized diet.

In fact, most of the 21 countries bordering the Mediterranean—many of which are in Africa or the Middle East—are not represented in the Mediterranean diet. The diet even excludes some areas that include Blue Zones, the five communities with the longest-living residents in the world.

Not many experts dispute the benefits of a diet that features mostly vegetables

and minimizes meat and sugar. It works for Johnson herself: “I have an autoimmune disease called systemic lupus erythematosus, and the Mediterranean diet is highly recommended for people like me because it’s high in anti-inflammatory foods,” she says.

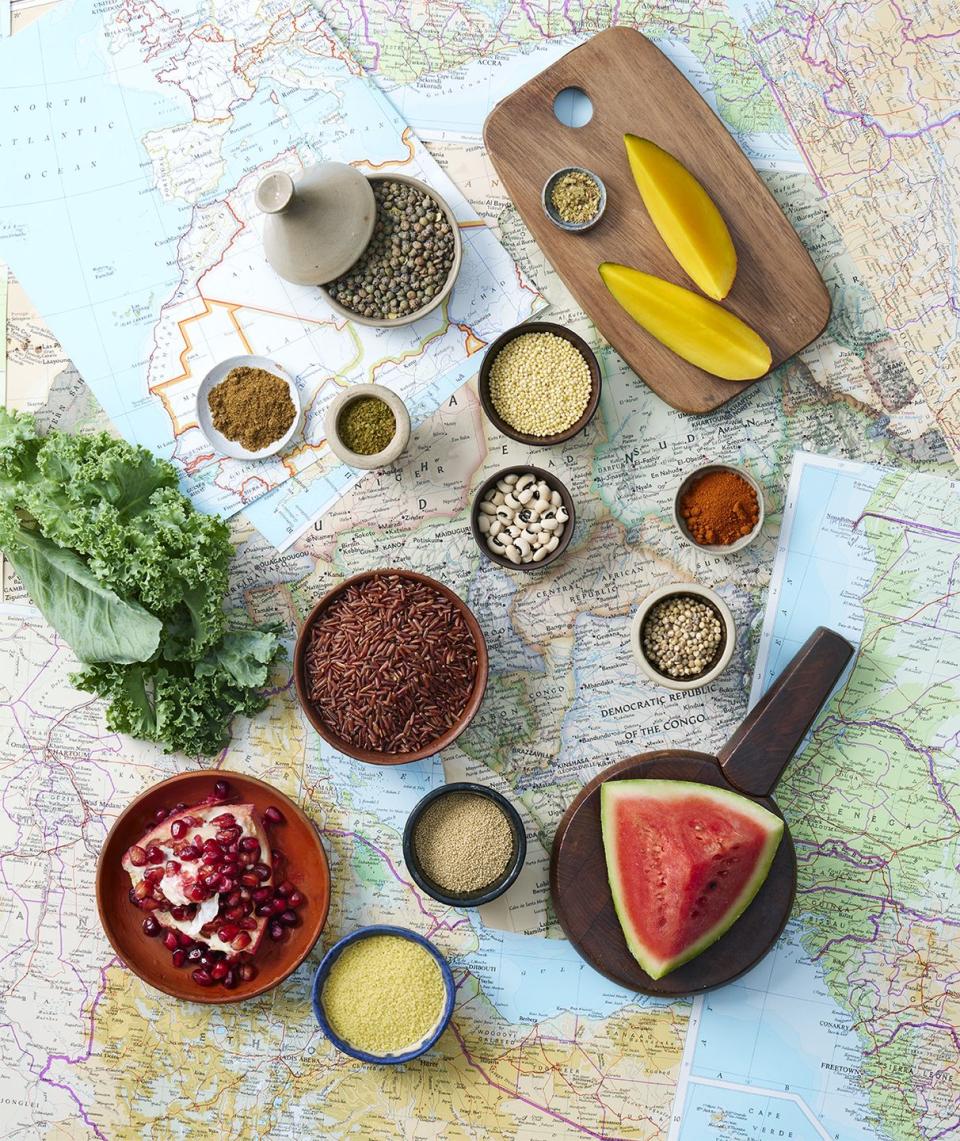

The problem is the centering of the Mediterranean diet in our collective Western culture. Many Asian and African diets have plant-based traditions as well, and many cultural foods can be adjusted to up their nutritional benefits. For example, foods from Ethiopia, Morocco, Pakistan, China, and India include many vegetarian dishes high in fiber and plant protein.

Where we go from here

When people are told that they need to abandon their cultural foods to improve their health, Johnson says they’ll often avoid following a prescribed eating plan at all. So the first step is to reclaim these foods in a nutritious way.

To start with, Iu recommends making small changes to your current diet that don’t take away your enjoyment of cultural foods. For example, you can change the cooking method—say, by swapping out fried foods for ones cooked in an air fryer. “I’d suggest focusing on adding fruits and vegetables where it makes sense and still honors your culture and taste buds,” Iu says. “So to make a stir-fry, you don’t need to use cauliflower rice instead of white rice. You can use white rice and add other veggies that you enjoy.”

Chef and founder of Todo Verde Jocelyn Ramirez, also a food-access advocate and the author of the cookbook La Vida Verde, says she did this when she created plant-based versions of the foods she grew up eating that were “culturally relevant” to her community. For example, she created vegan versions of pipián rojo and mole. “In Latinx communities, as I’m sure is true in many communities of color, food is so centric to the way we live together,” she says.

Individuals can start moving beyond the Mediterranean diet through books and blogs that dive into how to embrace their culture with health in mind. Books such as Decolonize Your Diet by Luz Calvo and Catrióna Rueda Esquibel and The Southern Comfort Food Diabetes Cookbook by Maya Feller as well as blogs like Plant Based RD and Your Latina Nutritionist can help you connect with your cultural foods in a health-conscious way.

Additionally, to turn the tide toward more culturally affirming advice, the food science, health, and nutrition industry must become more committed to inclusivity. Johnson points out that this is not an issue of Black and white. She says that both a white dietitian working with a Mexican patient who eats chilaquiles and a Black dietitian working with a Vietnamese patient who often eats pho may struggle to offer recommendations. Improving the advice given requires considering the experiences, food culture, and social determinants of health that affect the Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) communities, Iu says.

Adding cultural foods to future research, nutritional recommendations, and classroom discussion will create a more comprehensive approach on a larger level as well. Nutrition experts can then bridge the gap and see better outcomes for their patients that will have positive ripple effects in families and communities.

Ultimately, Johnson thinks change is possible, especially if more dietitians

of color enter the field. “The knowledge is out there,” she says.

What about access?

The difficulty a person may have in getting their hands on healthy food can be another barrier to following popular nutrition advice. Research has shown that Black households are three times as likely to be food insecure as white households, and low-income communities face both geographic and economic barriers to healthy choices. These families often live in food swamps (areas in which processed and packaged foods are more widely available than healthier options) and food deserts (areas where there are not many grocery stores or fresh foods available).

The popular advice to eat whole foods over processed foods is problematic when processed foods are all someone has access to, notes Nyemb-Diop.

Additionally, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, poverty has a direct correlation with obesity rates, and low-income communities have higher rates of heart disease and diabetes and often lack the education, access, and funding to allow for proper nutrition.

Ramirez says that people in her community are surrounded by fast-food restaurants and convenience stores. Businesses using quality ingredients and paying employees equitably often have greater operational costs and charge higher prices. To combat this, Ramirez plans to create a sliding-scale community bowl and offer discounts at her forthcoming restaurant.

Organizations such as Just Roots provide resources for those seeking solutions to food justice issues. You can also help connect families and communities with healthier food options by supporting organizations such as the Food Empowerment Project and the Partnership for a Healthier America.

You Might Also Like