Are millennials really the anxiety generation?

Ask an expert and they’ll tell you feeling anxious is completely normal.

“Everyone gets anxious about a presentation,” Sharon McCallie-Steller, a therapist at the Mountain Valley Treatment Center in New Hampshire tells Yahoo Canada.

ALSO SEE: Nearly half of Canadians suffer from anxiety — and many believe there’s no cure

“It’s very normal for someone if you go for a job interview to experience some level of anxiety,” says Marinela Trickett, a registered psychotherapist based in Guelph, Ont., with Psychology Today.

Experts also agree anxiety becomes a problem when it interferes with our everyday lives. And if you look at the numbers, you can see why more people than ever are speaking out.

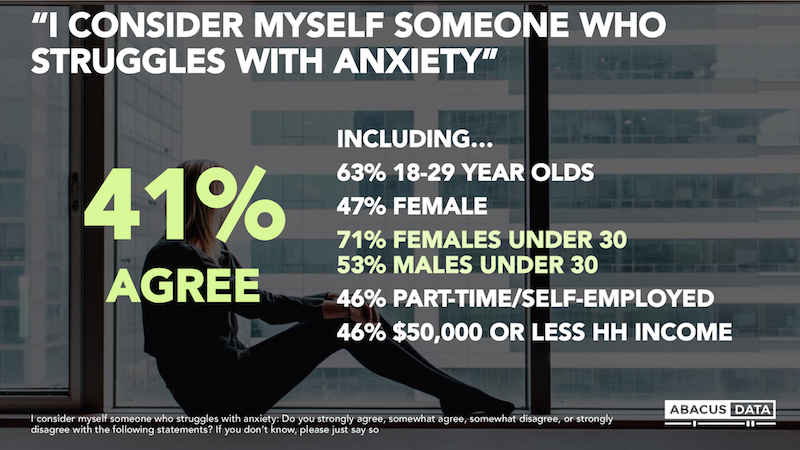

A survey conducted by Abacus Data exclusively for Yahoo Canada suggests 63 per cent of adults under 30 say they struggle with anxiety. This includes 71 per cent of women between the ages of 18 and 29 who consider themselves anxiety sufferers.

Young adults surveyed are reporting higher levels of anxiety than people who are self-employed, part-time workers or who make less than $50,000 per year, the poll suggests.

Clinically speaking, therapists define anxiety as excessive fears of the unknown based on perceived future threats.

“Whether the threats are real or not, the anxiety is very real,” Trickett explains.

As real as the feelings may be, it certainly isn’t a new phenomenon, according to social researcher Hugh MacKay, who has written 10 books on the field of social psychology and ethics.

“We’ve been having anxiety generations since the end of World War Two,” the author says, pointing to the 1950s, ’80s and ’90s as examples. The fear of nuclear annihilation during the Cold War heightened anxiety levels while many of these millennials were being born.

But MacKay admits there is something different about this generation, which he defines as anyone born between 1977 and 1993, making them ages 25 to 40 by the end of this year.

“If you want to see what the times are doing to us, take a look at the millennials and the current crop of adolescents.”

‘The options generation’

McCallie-Steller says she sees the anxiety problem in young people as being close to an epidemic.

“I don’t know if it’s generation so much as situational,” she says. “If you do research worldwide, anxiety is showing up in cultures that it never has been before.”

MacKay outlines two main reasons for why anxiety is so prevalent among millennials in 2018, a generation he calls “unusual.” He says they’re feeling deep uncertainty because of instability in the world combined with the uncritical embrace of new technologies.

“They live in a world of such radically-changing situations and such unpredictability and they’ve grown up with such insecurity and anxiety, and that has fuelled their anxiety,” he says. “I call them the ‘options generation’ because they’ve kind of adapted to the uncertainty by saying ‘I’ll keep my options open.'”

This is true with regards to everything from careers to home life. For example, the average age of mothers in Canada at childbirth is now over 30, which Statistics Canada calls the oldest age on record.

“That’s thanks to the tendency of this generation to postpone everything because everything is so uncertain,” MacKay acknowledges. “They are a very unusual generation.”

The fear of failure is real

McCallie-Steller says the need for instant gratification combined with the lack of teaching patience and self-reflection is only exasperating anxiety levels in this demographic.

“Are we teaching and learning how to be OK with things not going well? To be OK with uncertainty? To be OK with whether we have all the answers or not? To be OK with not getting the response quickly? To be OK with not having the answer?”

Parents play a role in this, too, as many children have been taught to fear failure, according to McCallie-Steller.

ALSO SEE: More from our Anxiety series

“What is it that makes parents of the current generation feel as though their kids can’t be disappointed? Or that they don’t want to let them fail because they’re afraid of how that might make them feel. Really, what ends up happening is then they don’t have the resilience to overcome difficulties and they don’t learn those lessons.”

Trickett says this allows children to develop negative core beliefs, such as “I’m not good enough” or “I’m incapable,” which is a vital part of our upbringing.

Young people are also living in a world where there is more information than ever before, and which can be a blessing and a curse.

“Our evolution hasn’t caught up to how to kind of manage all that influx,” Trickett says. “If you see the world as a dangerous place … a person learns that.”

Humans need human contact

Trickett notes it’s common for people to turn to substances such as alcohol, drugs or even food to drone out their thoughts. Technology can be used to escape our feelings, which she considers part of the problem for millennials.

“A person doesn’t have the ability to realistically affect their environment in the present moment because they are not in the present moment,” the psychotherapist explains. “They miss the opportunity to learn about their inner emotional world.”

The fast-paced rate of change in technology recently has made an impact on us as human beings, according to MacKay. After all, we are “social animals,” he says.

“The interesting thing about information technology is that while it appears to connect us, it makes it easier than ever for us to stay apart,” MacKay articulates. “When we are deprived of face-to-face contact, that tends to increase our anxiety level.”

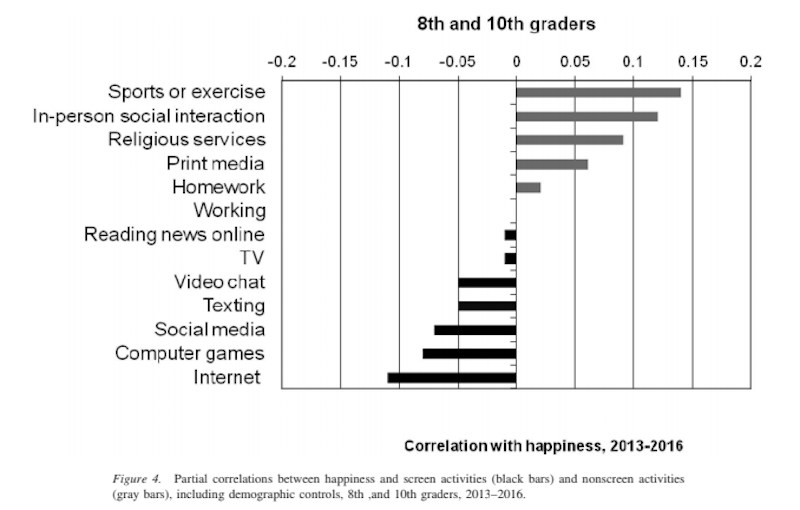

A 2018 study on psychological well-being by U.S. university researchers found “adolescents who spent more time on electronic communication and screens were less happy, less satisfied with their lives, and had lower self-esteem, especially among 8th and 10th graders.”

This is why the heaviest users of social media “tend to be the most socially isolated and most prone to anxiety and depression,” MacKay says.

“They’re missing out on what connects human beings, which is face-to-face eye contact.”

Mackay acknowledges he sees signs that the generation after the millennials will suffer the same kind of problems, “only more so,” and it might take another generation of suffering before humans self-correct.

“We have to monitor our screen time and make sure that it doesn’t exceed our face-to-face time,” he asserts.

Until that happens, this generation of young adults will have to adapt.

“We’re looking for a simple answer, and there really isn’t a simple answer,” McCallie-Steller says. “You’re going to get judged socially, there is no way that you will get judged by other people. The question is, can you manage the uncertainty of those judgements?”

During the month of October, Yahoo Canada is delving into anxiety and why it’s so prevalent among Canadians. Read more content from our multi-part series here.

Let us know what you think by commenting below and tweeting @YahooStyleCA and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

Abacus Data, a market research firm based in Ottawa, conducted a survey for Yahoo Canada to test public attitudes towards anxiety as a medical condition, including social stigmas and cultural impacts. The study was an online survey of 1,500 Canadians residents, age 18 and over, who responded between Aug. 21 to Sept. 2, 2018. A random sample of panelists were invited to complete the survey from a set of partner panels based on the Lucid exchange platform. The margin of error for a comparable probability-based random sample of the same size is +/- 2.53%, 19 times out of 20. The data was weighted according to census data to ensure the sample matched Canada’s population according to age, gender, educational attainment, and region.