Paolo Roversi Talks Luck, Instinct and Working From the Soul

PARIS — “I really like it when things happen by accident, when a photo doesn’t come out as I planned it but surprises me instead.”

With that, Paolo Roversi sums up the spirit of an exhibition at the Palais Galliera museum in Paris that covers his 50-year career.

More from WWD

A painter of light and shadows, the Italian photographer is known for a visual style that leaves plenty of space for accidents, experimenting with large-format Polaroids, a Mag-Lite flashlight and long exposures to create dreamy images with a timeless feel.

“I don’t like programming things. I like to allow myself to be guided by luck,” he says during a preview visit of the show, which opens on Saturday and runs until July 14.

Roversi and curator Sylvie Lécallier selected the 140 works, including previously unseen images and archives such as magazines and catalogues, from his personal archives at his studio in Paris, where he’s been based since 1973.

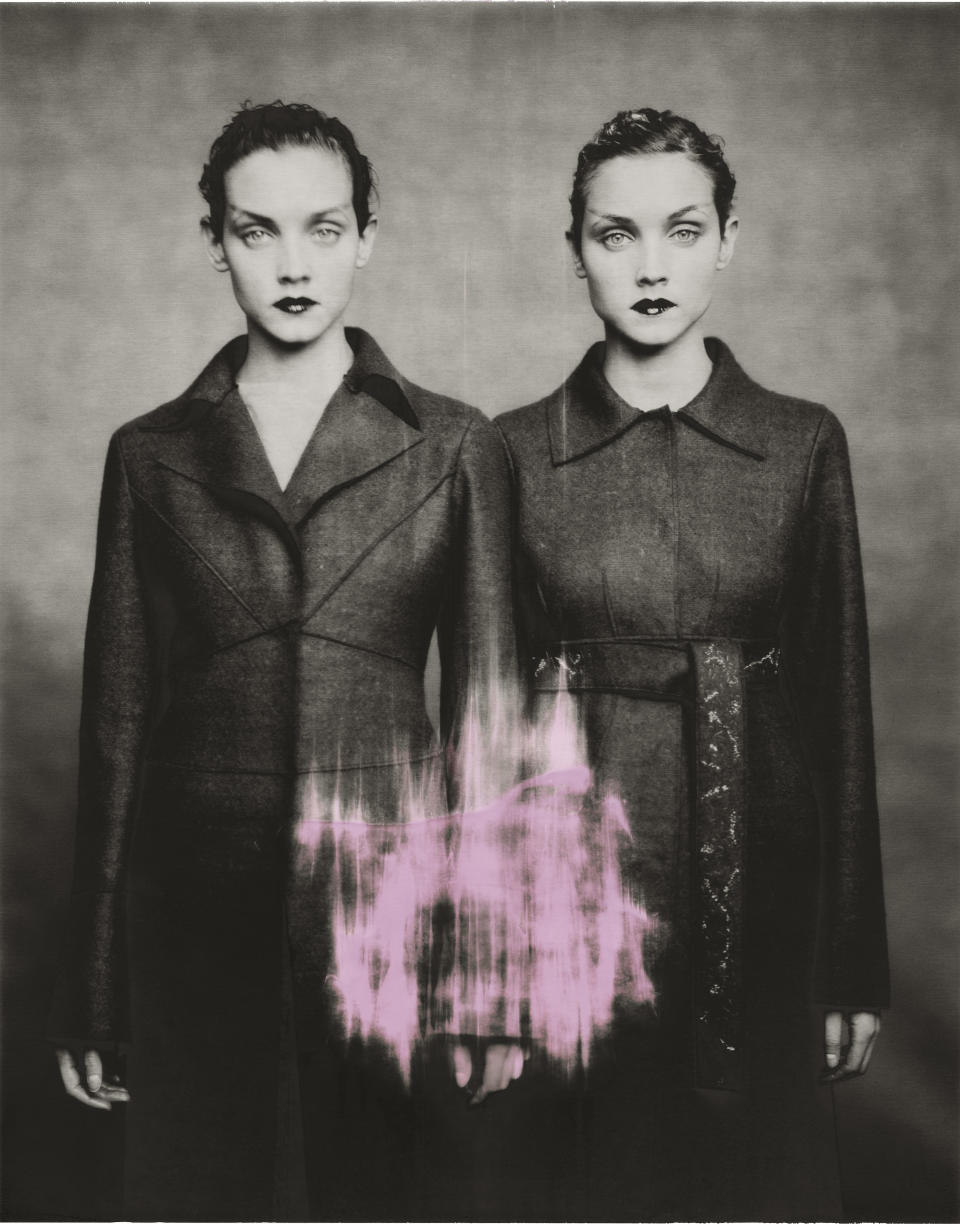

“I don’t like to throw anything out,” says Roversi, pointing to a 1996 Polaroid of Audrey Marnay posing in Comme des Garçons, her arm glowing bright red.

“When I took that one, I didn’t like it at all,” he remarks. “Ten years later, when I opened the box, I saw it and I thought, that’s the best one. So with hindsight, I sometimes see the images with a different eye.”

The exhibition marks Roversi’s first major show in Paris, and the first time the Palais Galliera has dedicated a monograph to a living photographer. The images are presented in no particular order and without wall labels, in order to encourage contemplation. “It’s not a real retrospective, but more like a diary,” he says.

A small booklet provides descriptions of the works, which include campaigns for brands including Yohji Yamamoto, Romeo Gigli and Comme des Garçons as well as editorials for Vogue Italia, Uomo Vogue and W magazine. But mostly there are portraits, with subjects including Kate Moss, Naomi Campbell, John Galliano and Rihanna.

“I approach each photograph like a portrait. For me, the subject is always the center of the world. I try to forget everything else to focus on my sitter, and there’s a real exchange,” Roversi says. “That’s what moves me.”

He frequently returns to favorite models such as Kirsten Owen, Guinevere Van Seenus and Natalia Vodianova.

“You develop a sort of photographic friendship that allows you to go further, because you know each other better, the mutual respect is stronger and it gives us more freedom to work together, and that’s interesting. Whereas when I work with a model for the first time, there’s more hesitation, more shyness, and that hampers creativity a little,” he explains.

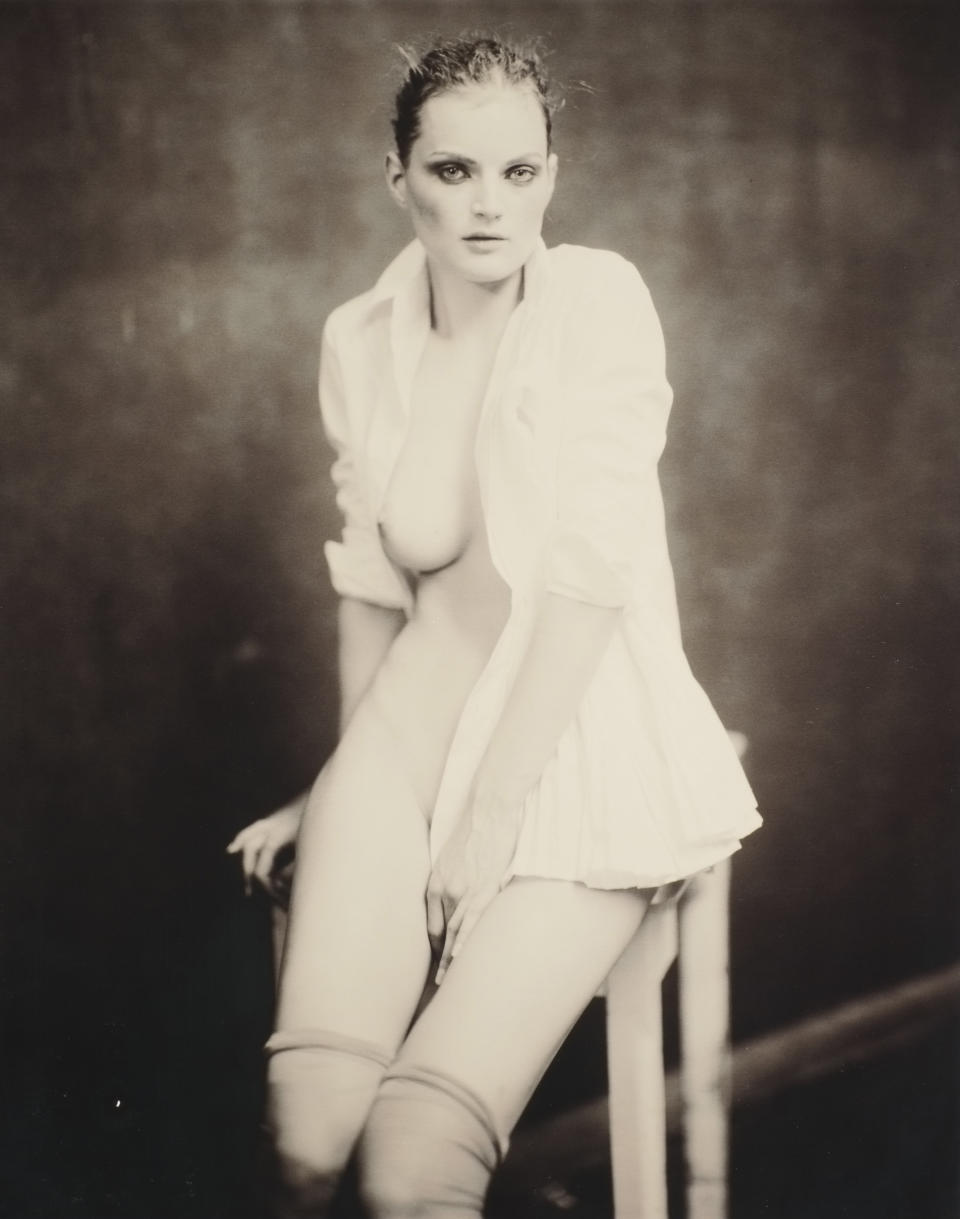

Roversi is fascinated by women with strong personalities, capturing their frontal gaze or nudity in a series of evanescent images that resemble drawings. In the stillness of a pose, he tries to seize their essence.

“They are true artists,” he marvels of his models. “It’s not like actresses who have a storyboard, a script, a set design or directions. They are in an empty space and with a gesture, a simple look, they tell a whole story. I find that wonderful.”

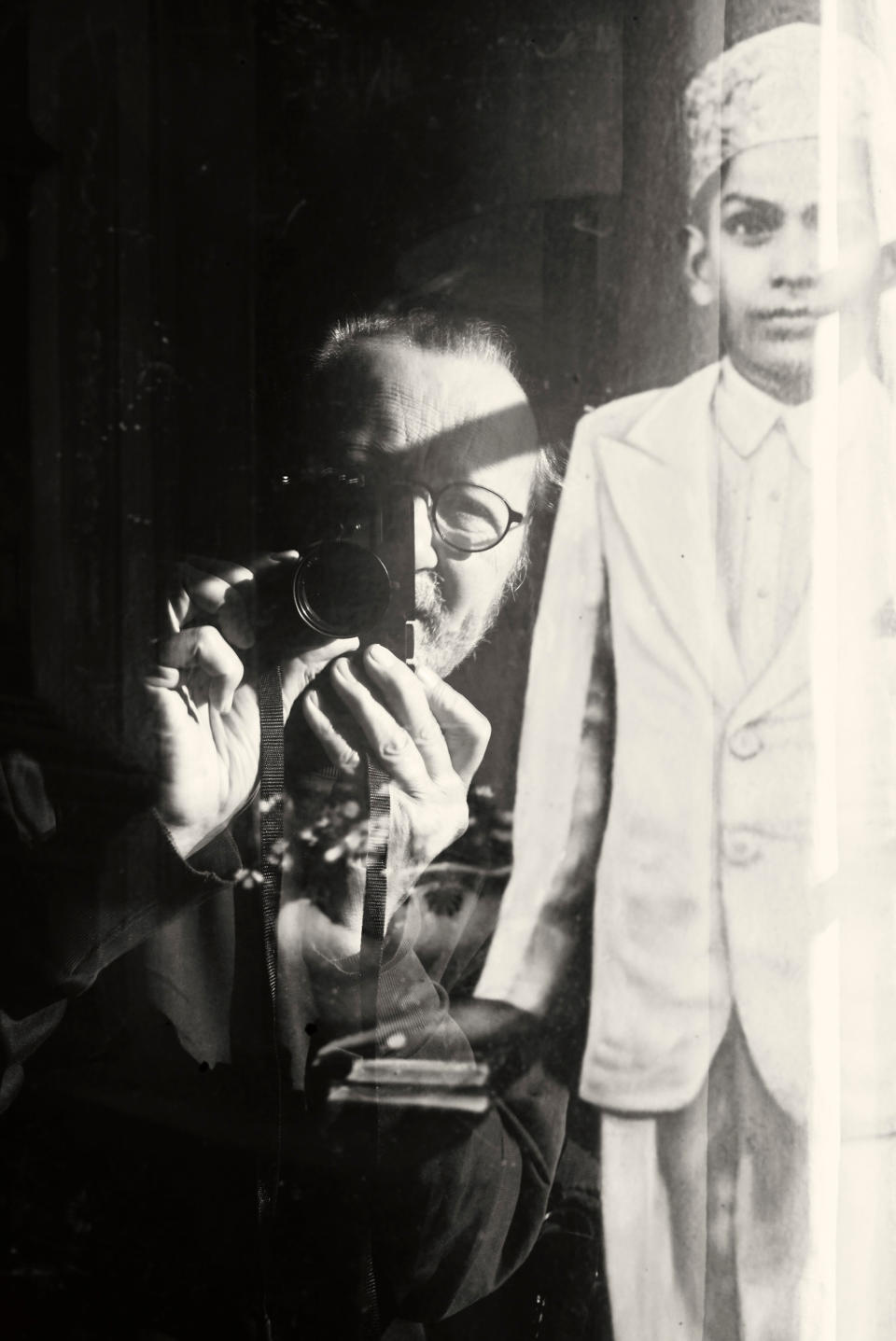

Lécallier says Roversi’s work was influenced by great portrait photographers like August Sander and Nadar, as well as Surrealists like Man Ray and Erwin Blumenfeld. She notes that he never works outside of his spartan studio, which appears in several shots.

“He’s a photographer of closed spaces in which he invents his own universe and transforms everything that enters,” she says.

Self-taught, Roversi has an encyclopedic knowledge of the history of photography and is comfortable with his position in it.

“Unlike many photographers who have a bit of a complex about being fashion photographers, it doesn’t bother me at all because I believe there’s nothing demeaning about being a fashion photographer. On the contrary, it’s something very important and noble,” he says.

“There are war photographers and peace photographers, and we are the photographers of peace, of wellbeing, of life and joie de vivre,” he adds.

Scrapbooks from 1978 to 1983 show how Roversi recorded his various technical experiments as he searched for his aesthetic. A Dior makeup campaign in the early ‘80s represented a breakthrough, but he’s still not sure he’s nailed it.

“I think style is not something defined, logical or arithmetical. For me, the style of an artist is his soul. It shines through in his work,” he demurs. “It’s definitely not a technique.”

He laments that the evolution of the fashion industry makes it increasingly challenging to work unfettered. “Today, everything is different,” he says. “There are a lot more restrictions, there is less budget. All of this makes it harder to keep your own freedom.”

Although he’s working less these days, the 76-year-old still revels in the alchemy of capturing clothes.

“The designer and the stylist write the score, and the photographer is there to interpret the score,” he says. “The models are a bit like the instruments, the violins, the pianos that he chooses to play this score.”

But one of his favorite images shows his empty studio, with just a pair of shoes on the floor. It was another fluke: Roversi had set up a large-format camera for the shot, but the model’s makeup needed a touchup.

“She took off the shoes and left them there, and went to get her makeup done. And that’s when I pressed the shutter,” he recalls. “I love this photo because it sums up my work: presence, absence, life, death, space and time.”

Best of WWD