For Pride, Lexington couple celebrates ‘a queer medical shotgun wedding’ | Opinion

Eleven months and one day after Shayla Lawson and Michael Hunter had their first date at the Lost Palm Bar on the rooftop of the Manchester Hotel, courtesy of an online dating app, they returned.

This time, Lawson was decked in white tulle and blue leggings that they put on in the hotel restroom; Hunter wore a blue suit and pink hair. This being Lexington, the officiant was Lawson’s best friend from the Governor’s School for the Arts back in high school. With seven friends and family watching as the sun went down behind the Distillery District on May 31, Lawson and Hunter exchanged vows.

You can call it meet cute. You can see it as another success for social media dating services.

Or you can call it, as Shayla did, “a queer medical shotgun wedding” that took place in May but should be celebrated in June during Pride Month.

The short answer is that Shayla, 41, and Michael, 32, got married for love and because of that love, they also got married for healthcare. The longer answer is, well, a lot more complicated.

A dangerous world

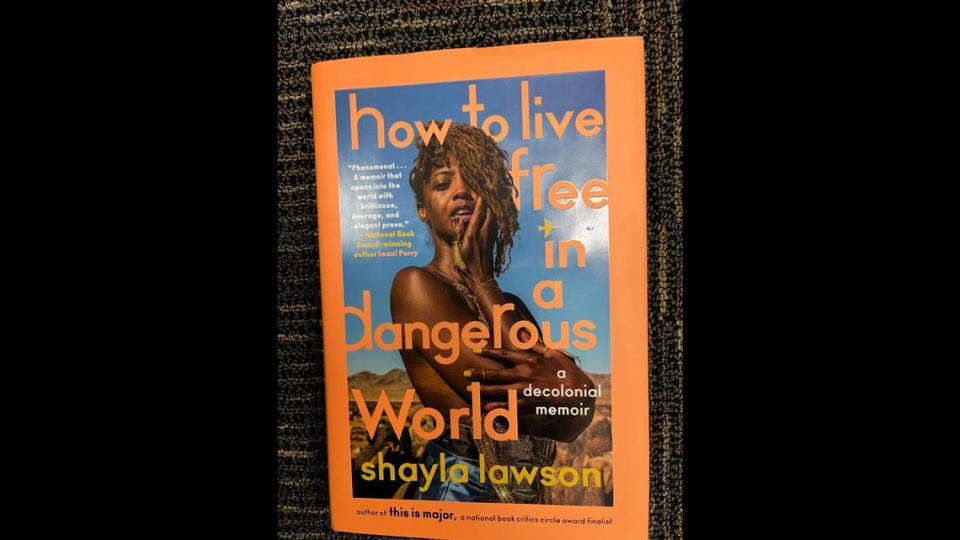

Shayla Lawson is a Lexington native who went to Dunbar and the University of Kentucky. They are also a trained architect, a poet, a writer of luminous artistry whose latest book, “How to Live Free in a Dangerous World: A Decolonial Memoir,” explores their identity through world travels.

Their previous award-winning books got them a job at Amherst College in Amherst, Mass. They could teach and write and continue to travel. Until one day in 2020 when both knees without warning would dislocated.

A few pain-wracked years later, after Lawson was told they would die in a few years, they were diagnosed with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, a group of rare, inherited conditions that affect connective tissues, like ligaments, tendons, bones or internal organs.

Some days or months are good ones without too much pain. Then, Lawson said, one day they tore through their rotator cuff reaching for a blanket.

Lawson had been in a constant dance with the Amherst health insurance service providers because Ehlers-Danlos is so complex and relatively unknown. Then the doctors said Lawson needed to take a leave of absence, which meant they would lose all health insurance.

That’s when Lawson and Hunter started talking about a not-so-distant future; the one they envisioned where they were together and something more immediate that included putting Lawson on Hunter’s healthcare plan.

Then something happened to speed it all up. At an appointment, Lawson’s doctor happened to remark that a pregnancy would be a death sentence.

“The doctor said directly it was too dangerous to leave to chance — the kind of medical situation I’m in, with Kentucky and red state politics and the abortion issue ... I can’t take the chance I would end up needing to have an abortion and not be able to get one,” Lawson said, curled up in their house under a pink neon sign blazing “This Must Be The Place.”

So Lawson had a hysterectomy. And together, they started planning their wedding.

“From the get-go, it was so romantic,” said Hunter, a former nurse who now works at the University of Kentucky.

“I’m just here trying to accept everything as it comes. Yes, there have been plenty of surprises, and of course, it’s not traditional or ordinary.”

Radical love and care

Sadly, what is traditional and ordinary about this story is that it’s yet another indictment of our porous, ineffective healthcare system and our cruel and barbaric reproductive healthcare politics. They just don’t always concur.

But it’s also a choice of how to live with radical love and care.

“More and more people are marrying for different reasons,” said Eden Davis Stephens, who officiated the wedding.

“I think people who are very much used to living outside of traditions, who live freely and creatively, still have to deal with the realities of life. Marriage is the fastest way to a lot of things — you get instantaneous benefits like insurance and survivorship rights.”

The health insurance became even more crucial when Lawson found out they were accepted into the Ehlers-Danlos clinic at Vanderbilt University, something that could give them much more health and freedom moving forward.

Lawson is still on book tour for “How to Live Free” and has a few select speaking engagements.

Then the couple will take a delayed honeymoon to Costa Rica, where they hope to look for a property that could become some kind of healing place for them and others. Lawson has already started a new writing project — a romance novel based on the story of their marriage.

Hunter and Lawson understand that in Kentucky, an open marriage between two queer, nonbinary people is confusing at best or at worst will bring hostility down on them. But they’re ready.

“Pride is a protest,” Lawson said.

“What we really love about being part of the queer community is how creative we are ... how creatively we solve problems. And so many of us are intersectional you know, it’s not just about being queer. It’s about also dealing with chronic health conditions or dealing with disability or being an artist or being from marginalized communities. And because of that, we have to figure out how to make lemons into lemonade pound cake all the time.”

The world we live in now is both dangerous and remarkably free and fluid. We are free to love whom we choose in whatever way we like. Even in Lexington, Kentucky.

Even if it scares some people.

“Neither one of us expected that we’re ever going to find somebody that made sense to us in life,” Lawson said. “But to see that we can build community and live our lives with this level of openness, but also the security of always having each other just makes a huge difference.

“One of the reasons why we feel telling our story is so important is to give people broader ideas,” Lawson added.

“People always just want to look at the cover and they don’t want to think about what’s inside the book. And we’re really working to build a relationship that’s about the whole story.”