How does religion impact anxiety?

Despite more people speaking openly about mental health than ever before, misconceptions and stigma related to anxiety society remain.

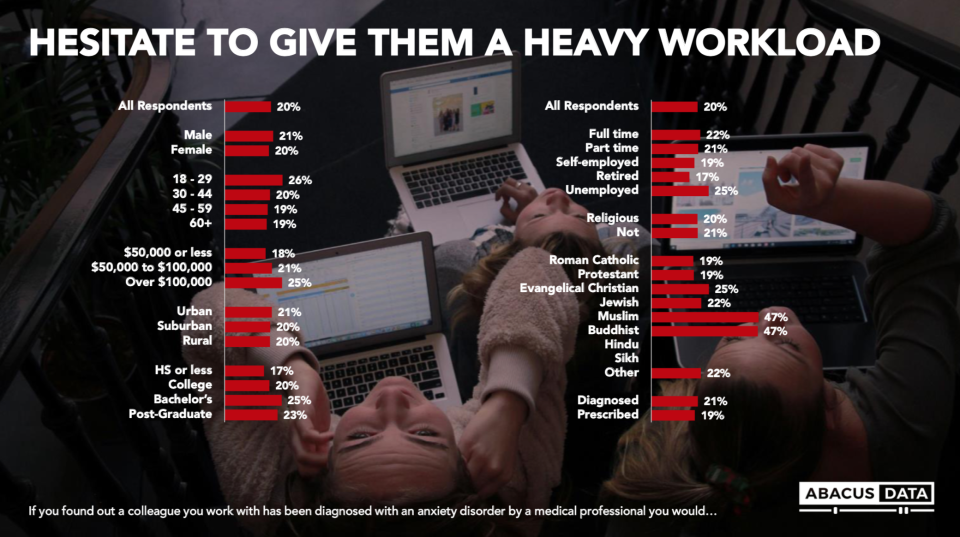

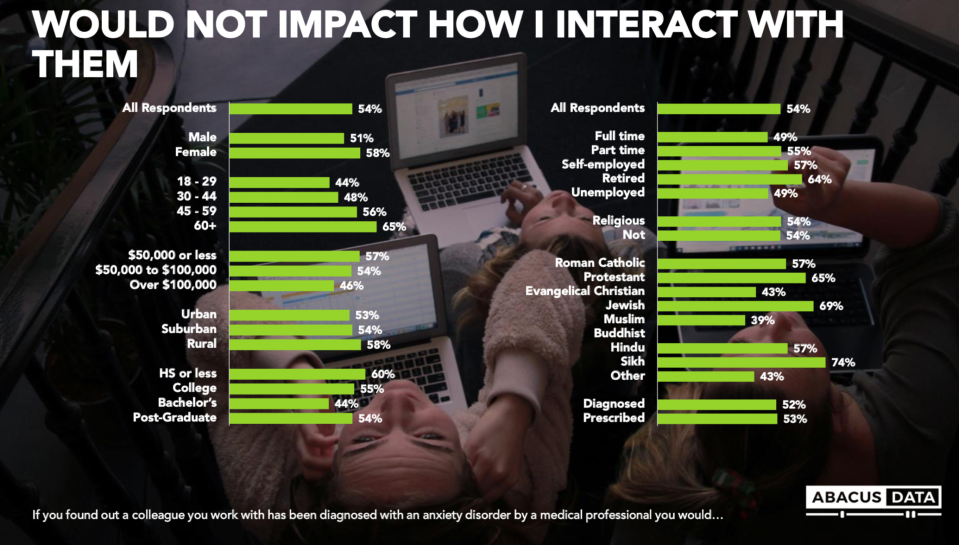

A new Yahoo Canada survey by Abacus Data shows mental-health literacy and openness varies among different religious groups.

While 34 per cent of Sikhs said they struggle with anxiety, 42 per cent strongly disagree that anxiety is a medical condition, the survey found.

Thirty-seven per cent of Roman Catholics said they struggle with anxiety, while just three per cent strongly disagree that anxiety is a medical condition.

Among Roman Catholics, 33 per cent said they have been diagnosed with an anxiety disorder. That compares with 13 per cent of Sikhs, 19 per cent of Protestants; 26 per cent of Jewish people, and 27 per cent of Muslims and Hindus.

No Buddhists reported being diagnosed with anxiety.

Respondents were also asked if they would avoid conversations about mental health with a coworker whom they knew had been diagnosed with an anxiety disorder. Six per cent of Protestants say they would avoid such a conversation, as would 26 per cent of Sikhs and 40 per cent of Muslims.

There are multiple possible reasons that anxiety may be perceived differently by various religions. People’s faith-based beliefs and cultural traditions can influence their views of mental illness — and their willingness or ability to accept anxiety as a medical condition.

Fardous Hosseiny, national director of research and public policy at the Canadian Mental Health Association, explains that, while mental illness is still sometimes mistakenly associated with weakness or human failure in society as a whole, that stigma is especially prevalent in various ethnocultural communities, including those within which religion plays a central role.

“It’s common among some Muslims that people don’t consider anxiety a medical problem but a test of faith,” Hosseiny says. “Within ethnocultural communities, mental illness is seen as a source of shame….There’s a real culture of silence that makes it more difficult to talk about for religious and cultural minorities.”

“Even if, anecdotally, you try to open up about struggling or dealing with depression or anxiety [among certain religious or cultural groups], you’ll hear from other people ‘You’re not like your cousins back home dealing with war and trauma. What right do you have to be sad or depressed?’”

Many Sikhs are hesitant to open up and talk about their personal problems because of the deep-seated cultural norm of “saving face,” according to a paper called “A Sikh Perspective on Life-Stress: Implications for Counselling” published in the Canadian Journal of Counselling by B.C. psychotherapist Jaswinder Singh Sandhu.

Not being able to discuss mental-health challenges often leads to the avoidance of seeking help, which can result in a crisis situation.

Maria Chiu, staff scientist at the Institute of Clinical Evaluative Sciences’ Mental Health and Addictions Research Program, has studied ethnic differences in the severity of mental illness among people in hospital for mental-health conditions.

Chiu’s research has found that Chinese and South Asian psychiatric patients were significantly more likely to be involuntarily admitted and showed more aggressive behaviours and psychotic symptoms compared to the general population.

“The most plausible reason for increased severity is the delay in seeking help,” says Chiu, who’s also assistant professor at University of Toronto’s Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation. “The hospital is a last resort, but what we’re finding is they postpone their help-seeking until it’s just too profound and they have to be admitted to the hospital.

“In some religions, some people feel that it [mental illness] is connected to something that they’ve done in their past life, and they’re being punished for bad behaviour,” she adds. “In some cultures, it’s because there’s so much emphasis on the family unit; it’s a family affair. If you’re seen as having a family member with a mental illness, it’s seen as poor lineage or as if the family is tainted. There’s a lot of misinformation and stigma and shame.”

Compounding the problem is that some people of different faiths are uncomfortable with the western way of thinking about and treating mental illness, Chiu says. They may be more accustomed to seeking the assistance of Eastern medicine or natural or spiritual healing than strategies such as taking prescription medication or doing cognitive behavioural therapy.

Experts agree that it’s vital to provide various religious and cultural groups with an integrated approach to treatment and counselling, one that considers and incorporates their religious and cultural practices and values.

“We need to make sure mental health experts leaders provide interactive and culturally safe conversations and make sure mental-health practitioners develop a targeted approach to different cultures and religions rather a universalized approach,” Hosseiny says.

One pilot study, based on a sample of 35 South Asian psychiatric patients diagnosed with depression, provided empirical support for integrating traditional healing resources with Western treatments as an effective therapeutic option, Singh Sandhu’s paper noted. He found there is a need to use traditional healing resources based on Sikh spiritual teachings as a culture-specific intervention.

Language is essential to successful outcomes; there’s no word in Punjabi for “anxiety,” for instance, and no term in Muslim for “stigma,” Hosseiny says.

Having family involved in treatment is vital, too. Chiu says mental health services must consider ways to increase people’s support system beyond post-discharged follow-up with their family doctor.

“What are community and social services that might be available in their language?” Chiu says. “Or are there churches they attend or organizations they’re involved with that can provide support, so they have something aside from medication and follow-up visits with their GP?

“You have to have the family buy in,” she adds. “Once you have family in place, you’re much more likely to have success.”

During the month of October, Yahoo Canada is delving into anxiety and why it’s so prevalent among Canadians. Read more content from our multi-part series here.

Let us know what you think by commenting below and tweeting @YahooStyleCA and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

Abacus Data, a market research firm based in Ottawa, conducted a survey for Yahoo Canada to test public attitudes towards anxiety as a medical condition, including social stigmas and cultural impacts. The study was an online survey of 1,500 Canadians residents, age 18 and over, who responded between Aug. 21 to Sept. 2, 2019. A random sample of panelists were invited to complete the survey from a set of partner panels based on the Lucid exchange platform. The margin of error for a comparable probability-based random sample of the same size is +/- 2.53%, 19 times out of 20. The data was weighted according to census data to ensure the sample matched Canada’s population according to age, gender, educational attainment, and region.